Angel

Dave

Darren DeFrain

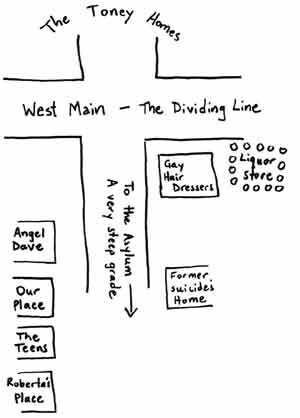

There is a clean divide in Kalamazoo, Michigan between the impecunious and haphazardly zoned neighborhood we lived in and the toney, manicured neighborhood across busy West Main, which ran from downtown all the way west to the shore of Lake Michigan (see figure A). To further heighten the effect our street took a precipitous and economically symbolic pitch down from the high point of West Main toward the crack houses and condemned asylum that once housed Malcolm X’s mother. Beyond all this was a quiet and shaded park, and beyond the toney neighborhood was a quiet and mostly empty former practice field owned and sporadically patrolled by Kalamazoo College. We liked to take our dogs (first two and then three Chinese Shar Pei) both places to run around after squirrels and do their business in the tall and pretty purple loosestrife at the edges.

Figure A

We bought a house in Kalamazoo when I started my Ph.D. program at Western Michigan University. It was a recently resided cape cod four houses from West Main that had been mostly refurbished inside and out. When I say mostly, its not to imply that some projects weren’t undertaken by the previous owners, they’d been comprehensive in their overhaul, merely that none of the projects had apparently been finished in time for them to sell the house. Fine, oak trim would have been laid along the baseboard, but would only have two screws holding the entire fixture in place. The walkout basement had a lovely, brand new full bath, but the toilet hadn’t been installed, and the walls hadn’t yet been painted. There were eight coat peg holes drilled along the wall descending into the basement, but only three coat pegs installed. I’m the antithesis of handy, so that is how we lived in the house.

The front yard was short and square, and there were two equally short, parallel gravel drives on either side of our house (one of which sloped sharply down toward the backyard, seemingly unabated and into the neighbor’s kitchen behind our own if the brakes on our car ever failed). There was a screened porch and a flowerbed where someone had buried a plastic Jesus. Having just moved to Michigan from Texas we’d never heard of this ritual to bring good luck to the home and its owners. There were plastic Jesii in Texas, to be sure (I don’t care if it rains or freezes, long as I got my plastic Jesus), but they were relegated to dashboards and computer monitors. So we promptly rinsed Him off with the garden hose and displayed Him in the porch window until He blanched from exposure and the spiders utilized His natural allure to entice green flies and lacewings. He became completely obscured by our ravages in just a couple, short years and I didn’t notice Him again until four years later when were cleaning the house to move.

We hadn’t accumulated much furniture during our honeymoon time in Texas, and as of our unloading into our new, imperfect home were without a couch for our little living room. Our neighbor toward West Main, a mustachioed and nearly naked man, wearing only a ragged pair of denim short-shorts and his neatly tied white, leather tennis shoes, noticed this. He’d been standing in his tiny, vibrantly green front yard dangling his hose in his hand to conscientiously drizzle every pruned, verdant blade of grass while smoking cigarette after cigarette, nodding occasionally, while we’d unloaded the van.

“I’m David,” he finally said, sticking his hand out to my wife, Melinda. “I know of a couch that would be perfect for you guys. It’s in great shape. It’s nice-looking, and they’re not asking much.” My arms were full of another box of CDs, which, at that time, still outnumbered our boxes of books, but I stopped at the top of the loading ramp long enough to look him over. His skin was slathered in shiny sun lotion, or was simply sweaty, and his hair was feathered back at the sides.

That night, sitting on the floor of our new house, our attention turned to Dave, who we could see through our exposed windows sitting on his porch igniting the tip of his cigarette like a firefly. “Did you notice that drink in his hand?” Melinda said. “I think he might be an alcoholic.”

I had only noticed the hose. “Why?”

“He had that cup in his hand all day long. And he was slurring his words. You didn’t notice that?” I didn’t, though I suppose I mention these details now as if I really did. “He’s probably depressed.” Melinda’s theory was that anyone with an immaculate yard who lived alone was probably depressed.

Out of guilt, mostly, we followed Dave’s couch tip, several miles out to one of his friend’s houses in the country, on a rainy Sunday morning. It was the kind of new-urban-sprawl-country-sub-suburban neighborhood that seems both comforting and sinister at the same time, like a hotel room. And there was the couch, sitting in the driveway ostensibly under a clear plastic tarp: a naked swath of floral confusion poking out immodestly, soaking in the downpour. To be fair to Dave we got out and pretended to be interested in the couch long enough to draw the couch’s owners out of their house into the rain to stand with us and stare down at it like some tragic accident. Which apparently it was, having been absent-mindedly left in the driveway overnight swelling into a mega-ton, flowery sponge. I felt vindicated that the owner of the couch seemed uncomfortable in the wet rain, and every time he shifted his weight back toward the house I tormented him with another question: How long have you had it? Do you have any pets? How long have you known Dave?

He finally got wet enough that he caved in and admitted what we all pretty much knew anyway. “Well, I guess you’re thinking it’s pretty much shot now that’s it got all wet. It could dry up real nice, though. And it’s comfortable when it’s dry. Or at least it was. Might still be, you never know.” I was relieved not to have to reject it the couch simply for aesthetic reasons. It seemed to do so would’ve been rejecting the taste and frugality of Dave’s friends, and no doubt, by extension, Dave himself.

We found a ridiculously cheap couch at Montgomery Wards, which came with a three-year warranty, even though it was a going out of business sale for the entire chain. And Dave watched, stood, and watered his lawn while Melinda and I navigated the narrow stairs into our living room. “Okay,” I said. “No dogs on the couch. Right?”

“Right,” Melinda said. We were relieved to be elevated off the floor, and we’d had to sit on the floor for so long that for a short while we both felt like we were levitating. By evening she was calling the dogs up onto the couch to sit by her. Our big male immediately started wiping his eye boogers over the plasticky material and our female licked herself and farted. Whenever she did this she would then look around the room as if to say, “What was that? Did you guys hear that?” Sometimes she would bark.

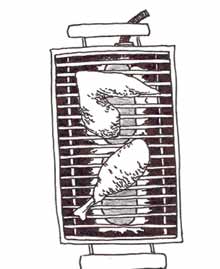

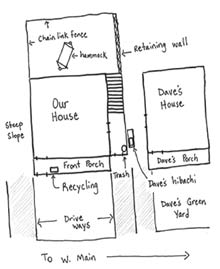

Dave claimed to love dogs, but we soon discovered a real neighborly problem between our dogs and Dave. Our house was only two driveway-widths distance from Dave’s house, and the only door that we could easily let the dogs outside to do their business from was on that same side (see figure B). We’d had a small, sharp-looking wooden fence installed on that side when we moved in, with an equally smart-looking wooden gate facing the street. There were stairs alongside a mason-block retaining wall holding up Dave’s yard that led down to our backyard which had a utilitarian chain-link fence surrounding it. Dave’s house, unfortunately, also let out onto the same side ours did, and Dave would frequently cook his dinner at a small hibachi he’d set up against this new fence. In fact, he always cooked his dinner there, regardless of the weather. A hamburger, a chicken leg, one or two lonely kebobs — there was always meat cooking at Dave’s little hibachi (figure C).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Figure B . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Figure C

The problem was that we couldn’t let the dogs out in the evening because they would congregate at Dave’s hibachi and bark and snarl and jump at him. I don’t know if it was the meat smell, or the alcohol smell, or the fact that he was so close to their backyard, but in the four years we lived there the dogs always acted as if Dave was some kind of bear making a move on our garbage (which because of some complicated logistics with the fence that I won’t go into, we’d had to move just a few feet away from Dave’s hibachi). But he was always gracious when we’d come to the door apologizing, trying, begging the dogs to shut up and come inside. “They’re fine,” he say, and reach a hand inside the fence always just obliviously missing the snap of berserk, slobbering jaws. “They’re fine. They’re just saying hello.”

The summer after we’d moved in I bought Melinda a hammock with a metal frame for an anniversary present. We loved that hammock, and on any day over forty degrees we would take a few minutes and lay on the hammock, down in the backyard, looking up at the impressive and varied canopy of leaves and birds and squirrels. There was even a cream colored squirrel, some near-albino that lived in the trees above our house. We liked to watch them jump from branch to branch, as did the dogs. Who would bark at the squirrels, or just stand under the hammock, leaning into the sag of our bodies.

Invariably, when we started to feel romantic from all of this Michigan splendor, Dave would call down to us from the top of the retaining wall. “You look like a couple of lovebirds!” We’d wave, politely. Go away now, Dave. The dogs would stumble out from under us, sending the hammock pitching back and forth, and clatter up the stairs in thunderous fashion, barking and snarling and confused that they could not actually get to where Dave was standing, his hose dangling from his hand, his cigarette dangling from his lips, his plastic cup dangling from his fingertips. “I said you guys look like a couple of lovebirds down there!”

Sometimes, after I’d shoved the dogs back inside the house and sealed them off from the world, I’d stand out there and talk with Dave anyway. I did this, I felt, mostly out of guilt over the dogs and the sense that his interruptions were a cry for help, which made the conversation uncomfortable. Like some kind of mutually beneficial therapy we’d been coerced into. Dave liked to talk about very few things, as I suppose did I, especially given the circumstances. He sold industrial-strength machines to clean your carpet, which, given the salivatory and unsatisfactory natural housebreaking abilities of our dogs, I actually shared some interest in discussing. He talked about which toxins kept which weeds best at bay, which given our green approach to gardening I politely ignored. And he discussed the neighborhood, over which he had apparently anointed himself sentinel and magpie.

During our time there he had proudly run off a couple of fraternity kids in the house on the far side of his who’d held weekend parties and littered the street with cigarette stubs and plastic keg cups (Michigan’s high deposit on cans and bottles has the added effect of reducing such trash). He’d threatened to do the same to the young, tattooed couple-plus-one (a scandalous threesome? Melinda had her theories) who moved in next door to us, opposite Dave. There was a blonde who looked quite striking from a distance, but when I saw her up close, while I was picking up after the dogs and she was wandering around her backyard, I noticed she had an enormous scar that ran from one ear all the way to her mouth, as if her face had once been cleaved in two. She apparently only lived with a couple. He had dark, brooding model good looks, and frequently paraded around shirtless to show off his six pack abs and his collection of dark and store-bought-sinister tattoos. She had long dark hair and Melinda and I would sometimes see her showering in their upstairs bathroom window while we ate breakfast. They never bothered to get a curtain for their shower, which seemed out of step with the relative modesty of the neighborhood. Dave clearly liked that people kept quiet and to themselves, so when the she and the he of the house began to have huge screaming fights that spilled out onto the street, car doors slamming, banshee-like shrieks and gravel-voiced epithets bouncing off the plastic siding of our houses, I could sense Dave’s fingers hovering over the 911. But he later told me he’d cut them some slack because, unbeknownst to me the tattooed he had a child by a previous arrangement, and the young couple (who lived with his cousin, the scarred blonde—shooting down Melinda’s theories) needed some time “to sort things through.” Dave wielded such communal power, and he dispensed it carefully and with great compassion, I thought.

He also told me the two men who owned and operated the salon on the corner, and who lived above the salon with their lordly and quiet greyhounds were gay. But even I managed that one on my own. He informed me the people directly across from us were getting a divorce, a couple of houses down were in bankruptcy, others had had unusual deaths in the family, impalements at the workplace, a tree squashing another, minor and major tragedy existed at nearly every mailbox. All of this interested me greatly, and I wondered if it was the same on the other side of West Main, but Dave’s omniscience didn’t extend that far. I also wondered what Dave might pass along about us?

There was the obvious, that we had dogs that barked and made fools of themselves whenever someone walked by. We had fights some times. Loud ones once in a while, but we contained them to the house. Surely only Dave heard those. We had b.y.o.b. parties with the grad students in the English program, sometimes during lean months just to get money from the empty bottle deposits. But these parties were mostly reasonable, and we were sure to invite Dave who always found an excuse not to attend. I’d see him perched up there in the dark at night, after everyone had gone home, though usually I’d pretend not to and he’d pretend not to be seen.

One night, after a party had cleared out, there was a ruckus down the street. It was a dark night, darker down the hill toward the crack houses, and I could just make out two people standing in the street, yelling at each other. One, I could tell, was Roberta, a large, gregarious woman with a dullard preteen son who lived in her mother’s old house.

Dave had filled me in that Roberta’s father had died a few years before we’d moved in and left the family pretty much penniless. There were four of them in that house, he said, the front rooms obscured by blankets in the windows. Their house squatted at the midpoint of our street, and the information from Dave now made it seem more and more like it was actually sliding down the hill toward crackville. I knew Dave was worried that houses like Roberta’s might have a kind of gravity to them that reached out to the houses up the street, our houses, and pulled them down with them. “Four people?” I said, I only counted three.

“There’s a four hundred pound brother who lives upstairs. He’s got… What’s that thing where you’re afraid to leave the house? Arachnophobia?”

“Agoraphobia.”

There was, at times, a boyfriend, who I assumed to be one of the parties in the street in front of Roberta’s house. Unlike Roberta, he never spoke, just stared the long, hard perpetually covetous stare of someone who had done time. He frequently stared at Melinda that way, and it scared me. He had a long pony tail and rode a bike with an enormous basket wherever he went. Melinda’s theory was that he’d lost his license for drinking and resisting arrest. She liked to make stories to go with what she observed about people like him, and Dave. My theory was that no one in that house had a car.

Sometimes, they’d be visited by the staring, pony-tailed boyfriend’s brother. He was gregarious, like Roberta, but scared me worse than his brother did. His teeth were gnarled and yellowed, his hair thick and untamed, and he had an equally untamed beard made mangy looking by the lunar landscape of scars underneath. One scar emerged through the hair like a river through a forest and flowed to the ocean of one blue eye. He looked like a David Bowie of the streets.

He walked up and down our street several times each day when he was in town. Mostly he walked over to the liquor store a few steps beyond the salon on the corner. One early spring afternoon I drove home from school, the streets still slick with melting ice, and as I pulled into our drive I saw he was on the front step talking to Melinda. I had that just-in-time feeling superheroes probably get, followed immediately by the what-do-I-do-now feeling regular people are plagued by. He walked quickly to the car before I could get all the way out and cocked his head so that I had no choice but to stare into the cold blue of that one eye, its pupil shrunk to the size of poppy seed. “Your wife said you’d have some work for me.” He said this with entitlement, like it was a threat.

“What do you mean?” I said, stalling, trying to gauge how I might get past him and into the house and lock the door. I looked for Dave, who was inconveniently out selling industrial-strength carpet cleaners.

“Yard work, something. I need some money.” This was ridiculous. We had almost no yard to speak of in the front, and the back, heavily shaded by Dave’s retaining wall and the surrounding pines and oaks, was a mess of dog poop and ice.

“I guess if you want to pick up the dog stuff in the back yard, that’d be worth a couple of bucks to me.” I was sure this would scare him off. When he paused to consider my proposition I added, “There’s a lot of it.” There was. It had been a long winter, full of snow upon snow, and I had given up trying to keep up with our dogs and their thrice-daily trips. We were feeding them too much, I realize now.

“Okay,” he said. “Show me what to do.”

I tried to argue with him that it was a job he really wouldn’t want to do, but I figured the best argument was simply to take him down there and show him. It had been a warm day, and our yard looked like an amateur archeological dig. Layer upon layer of dog bombs were exposed to the air, but it was still crisp enough outside that the smell was minimized. He shrugged, I shrugged, and then I handed him the wire pooper scooper and a hefty bag. Then I went inside.

“I can’t believe you told that guy I had work for him,” I said to Melinda.

“Well, I didn’t know what else to say. He was right up there on the porch telling me he needed twenty dollars for something. You know, I’ll bet he’s got something in hock at that pawnshop downtown. Or maybe he’s trying to get enough together for a bus ticket out of here. He’s been here a few weeks already.”

I tried to watch him out the kitchen window, but the angle meant I had to stand on my toes the whole time. I pulled a beer out of the refrigerator and then had a thought. I took another down to the yard to, you know, see how he’s doing. When I got down there he stood up and smiled at me, but I could see that the scooper was leaning against the stairs. “Um,” I said. “How’s it coming?”

“Fine. Fine,” he said. “But that piece of wire ain’t worth a shit. It’s easier if I just use my hands.” And to prove his point to me he reached down, bare-handed, and grabbed a handful of the slushy mess and slapped it into the hefty bag. He must have seen the look of shock on my face. “No big deal to me. I worked a hog farm down in Arkansas most of my life. Shit’s shit.” And he resumed scooping up the gooey mess like ice cream.

“Beer?” I said. It was all I could say.

“Yeah! Whew, there’s a lot of shit down here. You ever clean up after them dogs?” He grabbed the beer with his dirty hand and let of the bag with his other hand and twisted the top, which he neatly deposited in the back in the bag. Time was kind of standing still for me in that moment, but it looked like he drained the entire bottle in one slug. He then tucked the empty into his coat pocket in spite of the dog speckle on the label, then winked at me. “A tip,” he said, referring to the deposit. I went back in the house.

“He’s picking up the dog crap with his bare hands,” I said.

“Nooooo. No, he’s not. Not really,” Melinda said, and I could see even she couldn’t muster a story to go along with this. “Geez, how much are you going to pay the guy?”

“Well, we agreed on fifteen dollars?”

“To pick up dog poop with his fingers!?!”

“No, that wasn’t part of it.”

“You’ve got to pay him more than that!”

“Why?” Here was the problem: Did I actually pay him more for picking it up with his bare hands? Were there style points in such transactions? Paying him more than what we’d agreed upon would be embarrassing, surely. This was the kind of thing I’d have killed to have seen when I was in grade school, and I certainly hadn’t insisted he do this by hand, as it were. So why did I feel so bad about it?

Should I call our friends and invite them over? “Come on and watch us exploit the poor bastard from Arkansas for our pleasure!” Could I charge money? When I went back out to pay him he was rinsing his hands off in the cold water of the spigot. I was irritated to see he was leaving smears of shit all over the handle and the backyard looked a polar bear with diarrhea had just come through. His hefty bag, though, lay on the ground with its gaping maw spilling its dirty, classist secrets to the world. What was worse, the bag had almost as much shit over its shiny black outside as it did on the inside. I handed him a twenty and he began shoving his unclean hand in and out of his pants pockets searching for change. “No, no. You keep it. You do good work.”

The next morning, early, there was a knock at the door. I was still in bed and Melinda started down the stairs to answer it, but I could hear her stop short, after just a few steps. “It’s him,” she hissed. I jumped out of bed and tip toed toward the mouth of the stairs. “What does he want?” The pounding continued. “Oh God, what does he want this time?” We’d both just woken up, so our paranoia was probably a bit higher than warranted, but neither one of us wanted to go answer the door.

“He’s probably come to clean our toilets with his face,” I said. The pounding stopped. “What’s he doing now?”

“He’s stealing our recycling,” she said. She sounded relieved, but with a tinge of disappointment in her voice. I could hear the clinking of bottles. That seemed fair.

But now, late at night, there were two people screaming at each other out in front of Roberta’s house. “I’m going to kill you with this rock, you bitch!” One of the voices threatened. Was there a ponytail attached to the voice, or was it attached to the pony tail’s filthy-fingered brother from Arkansas, I couldn’t tell. This threat was followed by a cartoonish scream, the kind black women were always directed to make in 1950s circa films about slave life once the cannon fire began. And I knew then it had come from Roberta because I could make out her distinctive, ungainly gait out of the street and up the steps into the blanketed house. I didn’t actually see the lone person in the street make a move from where I stood, but there was the sound of glass breaking, by a rock, no doubt.

Just then I heard the muted tones of a phone being dialed. I looked up toward Dave’s porch to see Dave’s face illumined green by the glow of his phone, his cigarette plug hanging in the corner of his lime-colored face like a comma splicing Dave to his phone.

I went inside myself. The dogs were barking, so I let them outside to sniff around and satisfy themselves that nothing was intruding on their world. Dave wasn’t masking the familiar smell of their garbage with his hibachi, the squirrels were all asleep. Melinda came downstairs just as the blue/red/blue wash of a police car colored our living room, and the street beyond. “What’s going on?” she said.

“There’s a fight down at Roberta’s,” I said.

“So why are the dogs freaking out?”

I hadn’t noticed. The dogs were snarling and barking, like the time that cat jumped into the yard, somewhere in the dark back. I walked to the window and I could see that one of the police cruisers was pulled up in front of our house, our house now!, shining a spot down into our backyard. Had Dave finally called the cops on our dogs? I went to the side door and called to the dogs, who had worked themselves into a lather, but they were unresponsive to me. Something was bothering them.

I took a flashlight from the kitchen and, against Melinda’s warnings, walked down into the backyard. My flashlight was moving across the backyard now, running perpendicular to the cop’s searchlight coming down the opposite side of the house. I walked slowly to the fence where the dogs were going berserk, even for them. When I followed the searchlight up the hill toward the street I saw a dark figure stumble and fall, as if shot. I doused my light and ran back to the anonymity of the dark stairs.

The Frankensteinian figure stumbled up to the fence, the searchlight cutting across its scarred and hulking mass. “I know these dogs,” it growled. It reached down into the yard, as if to pet the dogs, but they lunged and tore at its great, hairy arm. “Ouch… Hey, you dogs,” it slurred. “I know these dogs.” Then it pitched backward, raising a now bloodied arm to shield itself from the light and, I swear, said, “Argh!” before falling down onto its back. It rolled over in the wet and decayed leaves and shadowy shards of new spring growth, and pulled itself onto its haunches when it let out an enormous farting sound, followed by another “Argh!” It pulled itself upright, facing the light now like the monstrous apes in Kubrick’s film, and I saw it was Roberta’s shit-picking-bottle-thief in-law from Arkansas. A cop emerged from the light, threw him to the ground and wrestled some cuffs onto him. The whole time he kept insisting “I know these dogs.”

Not long after that excitement I got a call from a small, Presbyterian college in the economic armpit of Pennsylvania, and I accepted the job. If for no other reason than to escape my guilt and pathos over Roberta’s family. It meant moving out of our house and getting it ready for sale in less than two weeks time.

Our guilt and pathos with Dave would be a little more complicated. When he saw the sign go up in front of our house he knocked on the door with a request. “Will you at least try to sell to a young family? Somebody stable.” He was in his work clothes, a gray suit with loose threads and some wear at the knees. He’d been dropping hints that the carpet cleaning market had been rough going lately, and we’d seen less and less of him puttering around his yard and more and more of either an empty driveway or the blue glow of his television set through his front drapes.

I asked Dave to borrow one of his carpet cleaners, to which he nervously acquiesced. He used a lot of carpet cleaning jargon, which I would’ve normally been very interested in (extractor instead of vacuum, that kind of thing), but we were in a hurry with everything right then. It was a gray metal box on wheels, and looked like a robotic baby elephant. I cleaned the upstairs first, and the sheen from the carpet was amazing, inspiring even. How could he not sell thousands of these things? When I worked over the living room, sucking out every last tinkle of dog stain from the fibers of the carpet, from the fibers of the house itself, I felt for a moment what satisfaction a job like Dave’s might yield. But by the end of the day, when my back wouldn’t straighten out, and I’d had to purge all the filth from the holding tank with my bare fingers twenty times over, I felt I understood even more about Dave.

We returned the carpet cleaner in as good of condition as we could, polishing it inside and out, and then collapsed onto the bare floor of our living room. All the windows in the house were open to let the ammonia and alcohol smells waft out. We were back to the same position we’d been in when we first moved to Michigan, dizzy from the hard work and déjà vu, when there was a knock at the door. “I told you you should have cleaned that containment trap better,” Melinda said. She had picked right up on Dave’s jargon.

But it wasn’t Dave at the door. It was an older black couple and a thirtyish black woman. They wanted to know if they could pour through the pile of refuse we’d left at the curb. All the old clothes and other casualties of moving we’d set out for the trash collector. “Sure,” Melinda said. “Whatever.” Then she shut and locked the door and plopped back down next to me on the floor. We listened to the birds outside and wondered what kind of impulsive mistake we might be making moving out to this job.

We could also hear the people at the curb picking through our cast-offs, ridiculing our taste in clothes (the nerve!), our boxes of useless old school notebooks, our stupidly broken knick-knacks. Then there was hysterical laughter. Melinda raised her head to look out the window in the front room. “Oh God,” she said. “They found that box from Derek!”

My friend Derek was a pharmaceuticals salesman, and the one time we’d visited him he’d passed along sample boxes of some new condoms his company was marketing for porn-star sized men. We’d tried a couple years earlier, but they were so big I could’ve used them better as leg warmers so they’d gone into a curb-side box. One of the women was peeling with laughter and repeating over and over, “He big! He BIG!” When they’d moved on we sheepishly looked out the window. They’d strewn our trash all over the sidewalk, but it looked like they’d taken the condoms with them. I was glad they didn’t find everything we’d tossed out so indiscreetly.

We slept on that clean floor that night, aiming to hit the highways south and east to Morgantown, West Virginia early the next day in our tightly packed van. When dawn came through the curtainless windows I was stiff and irritable. I let the dogs out one last time, and they immediately began barking their Dave bark. I wondered why he’d be out so early on a Saturday, but I saw he was already curling up his hose. “Sorry Dave,” I said, and pushed the dogs back inside with my legs.

“Hey,” he said. “There’s something you should know. Hold on, I grabbed it for you. I’ll be right back.” He disappeared inside his house and came back out holding a rolled up zip-lock baggy. When he shook it out it looked at first glance as if he’d captured someone’s middle finger.

Oh my God, I thought.

“These people were rifling through your garbage,” Dave said. “And then they were chasing each other around my front yard with this. I didn’t know if you meant to throw it away or what.”

“Melinda got that as a gag gift for her bachelorette party,” I said. “I think it was supposed to be humiliating.”

“Guess it’s done its work then. You still want it?”

“No! God no! Just throw it out,” I said. Dave nodded, but then he kept his find and walked back inside.

After renting the house out to a visiting poet we finally sold it to a college kid whose father thought it would be a good four-year investment. We couldn’t disagree, but we also knew that he probably wasn’t going to be the kind of owner Dave had in mind for the street. When we returned to sign the papers we saw that Plastic Jesus was gone. Maybe back underground. But hopefully something more miraculous, because with that final sale the street had slid one more house away from West Main.

Normally, I hate stories that end with a dream sequence, especially when nothing else to that point has been notably surreal. It’s contrived, and the metaphors seem always so patentedly Freudian or frustratingly elliptical. But, among other things, there’s this essay’s title to justify. So on our first night in our house in West Virginia I had a dream about Dave. As we pulled away from our house and onto West Main, out of town, I was watching him, in the dream, in the rear view mirror of the truck. He was shirtless, watering his yard, and watching us move our lumbering load onto that busy road. He took a giant drag from his cigarette and blew a smoke ring which hovered above his head, like he used to hover above the two of us in our hammock. The water pressure in the hose turned higher, and it lifted Dave right off the ground. And, then, I think there were cars closing in on us, I woke up and he was gone.

Cimarron Review 205 Morrill Hall English Department Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 74078 cimarronreview@yahoo.com