REVIEW

HEY PARKER, YOU BIT MY TWENTIES!

Jeff Parker, The Back of the Line, Decode Books, 2007

Jeff Parker, Ovenman, Tin House Books, September 2007.

Reviewed by Matt Dube

When I

graduated college, I moved on a whim to Kalamazoo, MI, sure that was the

place to start my new life as a literary bon vivant. In three

months, I was back washing dishes like when I was in school, but without

that soul-saving distraction of working towards a degree. I went to punk

shows and drank malt liquor and skipped a job interview that could have

led to better dishwashing job because I was afraid of what a comprehensive

drug test might turn up. I wandered in a featureless desert of my own

making. It only took three years for me to swallow the grad school hook

that's tugged me consistently and kindly to where I am now, but I've never

been so unsettled as I felt then, so unsure about where I was going or

more tied into the minutiae of the everyday: bands, girls, bus schedules.

Jeff Parker's The Back of the Line

and Ovenman bring a lot of that stuff back. I've got boxes somewhere

full of stories I wrote about working in kitchens, but they lack Parker's

fresh language or the sturdy, unashamed narrative pedigree of Ovenman,

the story of When Thinfinger, kitchen slave turned expert evolved to night

manager. I knew a series of people who lived in the house actually on

the grounds of the cemetery in Kalamazoo, a creepy drug haunt, so when

James, one half of the dynamic duo whose adventures are storied in The

Back of the Line, ends up sleeping in a mausoleum, "after being pursued

by police and irate neighbor," (unpaginated, but from the story "James's

Low Moment") I feel like I'm on familiar ground. The details in the

novel and the book of stories feel right-on and retain that pressed sense

of novelty even when they are recognizable. These are stories about young

men who get kicked around some, who don't fit in and who don't have a

lot of options, but in Parker's hands, they don't get too weighty or read

like they are about social problems: they are stories about vibrant, lively,

and often very funny characters. These books, after all, are literary

creations, and Parker is unsparing when it comes to giving literary pleasures.

This is especially true in Ovenman,

where over the course of the novel Parker riffs on the brilliant, bombastic

language of one When Thinfinger, pizza cook and then night manager at

Gainesville, FL's Piecemeal Pizza by the Slice. When is a skater, which

is a milieu Parker describes with effortless authority, but even that

underground community, surfing's runty cousin, can't fully account for

the novel imagery Parker invests Thinfinger's language with. Describing

the wait for a motorized mail-order skateboard to arrive, Thinfinger comments,

"Days go by like surgery while I wait. It takes a week" (11).

This linguistic freshness nourishes a book where the character arc is

essentially the same as Spiderman 3 and a hundred other "coming

of adulthood" stories: how to not be insufferable when you are finally

getting what you've long deserved. Reading the book like a dutiful reviewer,

I tapped the page as I read certain scenes and mentally noted the first

turn, the apotheosis, the climax. But despite the narrative arc's schematic

regularity, the details along the way are as distinct and new as Parker's

language. When we need to see Thinfinger in control, but Parker wants

us wary of what this kind of control can do, Thinfinger and co-worker

Gutterboy pass out slices of pizza cooked in easy-off oven cleaner, a

problem Thinfinger tries to massage without admitting it's a problem.

When the novel's first crisis arises, the threat to Thinfinger's girlfriend

Marigold, it's because she failed to execute a bunny hop on a $2 yard

sale Huffy. The moves themselves might be familiar, but the actual details

from which they are made are constantly surprising, and the level of invention

overall in both these books makes them a joy to read. No shit, I found

myself laughing and cursing Parker for the things he came up with. And

anyway, I'm not sure anyone reads a novel for new narrative forms.

The challenge of short fiction is

different, and here I think Parker isn't quite as successful. The four

stories in The Back of the Line concern the adventures of slackers

James J. Wreck and the narrator, two more maladjusted malcontents who

would fit right in on the line at Ovenman's Piecemeal Pizza by

the Slice. The narrator is supposed to be watching his unfaithful girlfriend's

bird in one story, but can't stop James from hitting it with a hammer;

in the title story, James applies for the position of new boyfriend with

an ex-girlfriend, but will likely not be hired because of his low scores

on the math test she includes as a condition of employment; in another,

James wakes up in a mausoleum; in the last, James and the narrator work

replacing parking lot gate arms and scheme at less dead-end pursuits.

There's a sweetness in these stories, a lingering in the fantasy of twentysomething

daydreams, especially in the absurd turns of the first two stories. But

formally, the stories don't offer much; the language is flatly declarative

and without affect or energy ("The affidavit of responsibility is

something that can clear her credit if James doesn't pay up. James is

supposed to be paying up, but he doesn't appear to be doing that"

(unpaginated, from "James's Love of Laundromats")), stories

peter out rather than end. I don't mean to be too harsh about this, because

the same elements of world-building are present here as in Ovenman,

and the sense of sympathy and understanding of being stuck in these situations

is still present.

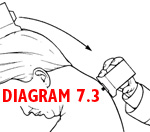

And maybe The Back of the Line

isn't meant to be that kind of book. What it lacks in diagrammable literary

effects, it makes up for in its design: the stories themselves are interspersed

with drawings by William Powhida—so the narrator will comment on

something, like the similarity in nose shape between James and his girlfriend's

bird, and there, in the margins of the story's text, is the doodle to

illustrate that point. In both the stories and the novel, characters struggle

with bureaucracy and red tape, always being asked to fill out forms to

the best of their ability. The forms themselves find their way into The

Back of the Line, where they are filled out, or not, depending on

the story. The words of the stories themselves are rendered in a handwritten

font that emphasizes certain words by printing them darker, setting them

off from the margin, etc. There's never a moment where there's an actual

illustrated sequence, where the action plays out through the images, unless

you count a Family Circus-esque map that straightens out some of the chronology

in "James's Low Moment." But taken together, it all makes The

Back of the Line a distinctly appealing volume.

Powhida also illustrates Ovenman,

and I think here, in the longer form, Parker is more disciplined about

how his storytelling evolves. Each chapter begins with Thinfinger coming

to after blacking out and finding a post-it he wrote that relates to what

he can't remember. In this way, the story is jumpstarted to recover what

led to the now. And the length of a novel humanizes the characters, so

that instead of the character in a long joke, like they sometimes appear

in The Back of the Line, the struggles of the characters here,

especially When, become important to us, and we can seriously consider

their philosophy, like this nugget from When about the joys and perils

of skateboarding: "When moving, there is no time to think" (158).

The novel and the book of stories are both concerned with the permutations

and devolutions friendships can undergo; in Ovenman, When struggles

with living in the shadow of his more-talented friend Blaise, and in the

last story from The Back of the Line, James sacrifices himself

so that the narrator can get ahead in the go-go world of parking lot gate

arm repair. But in Ovenman, the stakes and stages of this conflict

are more filled in, and the half-successful reconciliation between When

and his friend Blaise is more satisfying; in The Back of the Line,

James's sacrificial gesture, perhaps because of the need for compression,

doesn't even make it to the page but is reported on third-hand. Both books

by Parker are fun, and full of distinctively strange but vivid characters

and situations. If you come from a certain time and place, you might even

find large elements of both of these books appealingly familiar; I often

felt that I was reading about people I nodded at when I saw them in the

crowd at a show. Parker, though, has taken the experience of that no-future

scene of skateboarders, punk rockers, and kitchen slaves, and crafted

something worthwhile from it. He's gone some way towards redeeming some

years where it seemed to me likely nothing would ever amount to anything.