TASTE

Teresa Shen Swingler

I. Sweet

Anthill

The anthill is in front of my house. It started

with a cupcake I dropped on the ground, frosting first. The ants started

to congregate, carrying sprinkles and cake crumbs into the deep sidewalk

crack. A week later, they created the hill. Around it, we stand; you,

three other boys, and me, the only girl in the neighborhood. It is early

afternoon, the sun sits high in the sky, heat seeps up into our shoes.

I am holding a pot of boiling water. The bubbles have calmed down but

the steam rises into the hot air. You crouch down and peer into the ants'

world. They are marching in lines, busy, so busy, ever productive. They

march toward their home, hauling sticks and pebbles and grains of sand.

I look, too, but all I can think of is how you kissed me behind the shed

last week.

The ants march forward to the hole

in the hill. I wonder where it leads—to secret tunnels beneath the

earth, to a series of rooms and hallways we will never see, dark and cold

and private. You and the boys don't think of these things. One of them

pokes at the ants with a branch, the other smears an ant across the sidewalk

with the sole of his shoe. You pinch one between your fingers and smile

at me. Then, you say, with your head cocked and one shiny piece of hair

hanging over your eye -- "You gonna pour the water or what?"

I hesitate, looking down into the

pure, clear water. With all eyes on me, the waiting, I think about my

dad, a botanist, and how he meditates in the morning among the cobwebs

in our house, alone with the spiders, at peace with nature and all its

creatures. But, there is intensity in your stare—a promise we will

go behind the shed, again. Maybe you will stand between me and the wall,

lean into me, and put your mouth to mine. Maybe you will put your fingers

behind my neck. I tip the pot.

The water trickles at first, then

pours over the anthill with a big splash. You and the boys watch closely

as seventy-some ants that once had bodies, antennae, and legs, shrink

instantly into tiny black balls the minute the water hits them. The sounds:

they are high-pitched, like tiny squeals, as the heat makes them pop,

sizzle, and scream. I cover my ears and shut my eyes, and hear your laughter.

A week earlier, after our kiss,

while playing in a dirt lot behind an abandoned house, I stand invisible

behind a corner as you and your friends pee on the side of the house.

My legs are crossed tight. I need to go to the bathroom, too, but our

houses are miles away. I hear you say, too bad Mei can't piss like a guy.

Mei, you say, will stay out here as long as I want her to, if you know

what I mean.

You cross your arms and whisper "Sweet".

The air is hot and quiet, the earth stands still. Everything is still—the

anthill is completely still. I purse my lips and look into the sky, to

prevent those hot, hot tears from falling. You high-five your friends,

and you all turn and walk away.

II. Salty

The Shellings

For a minute, I got mad. He said to ease up, he would introduce me to

his family someday soon. It was just hard for them to accept, he said,

him dating a non-Muslim. Then he cocked his head to the side, smiled up

at me, and said "A hot one, too" and pulled me toward him. He

kissed me on the mouth, sticking his tongue inside, and I pulled away.

It wasn't that I didn't want to kiss him, it's just that this image kept

coming back to me, because of a story he told me earlier that day. Two

years ago, he went to Vegas with some buddies for a bachelor party. He

lost two hundred bucks at blackjack and couldn't afford to go to the strip

club, so he headed back to the hotel while the rest of the guys headed

the direction of the neon pink XXXs. I almost wish he had gone with them,

because nude girls wouldn't even really bother me that much.

Instead, he walked back to the Frontier,

a beer sweating in his palm. As he approached the hotel, he saw a hotel

employee leaned up against the outside walls of mirrored glass. She was

smoking a cigarette with her left hand. She had dark hair, and red lips

that matched the polyester red uniform she was wearing, with its gold

buttons buttoned all the way up to her chin. Her eyes, he said, were deep

set and familiar. I wanted to think she was some long lost relative—a

cousin, maybe, but no. He had never seen her before in his life, he just

recognized her as someone from his home country, Bosnia. And he also noticed

one of her arms was crippled; permanently bent at the wrist and elbow,

like the neck of a swan. He says he wasn't interested in her that way.

He just didn't meet people from Bosnia very often, so he went up to her

and started talking in their language.

"When did you escape?" he

said to her, just like that— he was probably feeling his beer by

now, which makes him much more direct and to-the-point, no frilly formalities.

She stared at him, for what he said

felt like five full minutes. She looked bored. Her bent arm emphasized

the bored look even more. She was probably thinking of a snappy comeback

like "The asylum? Yesterday," or "There is no escaping

the Frontier. Yee Haw." But she probably recognized in his eyes a

look I've never seen—a look of sincerity. Because she answered straight.

"'93. You?"

To which he replied "'94."

Then, he took both his hands and breathed

heavily onto the mirrored glass next to her, and with his finger, he drew

a box. He drew the window to the outside, then the kitchen area, pressed

his finger down as he drew the heavy wall between the eating area and

the rest of the house. Then, he drew circles for his father, his mother,

his sister and himself around the kitchen table, a circle for his grandmother

washing dishes, and a circle for his grandfather who was walking through

the hall. He told her he was eight years old on that first night of Ramadan,

the new moon right outside their one window, and they all gathered to

eat after dark. He took his finger and scratched through the little line

representing the window—that was where the shelling came in, and

a piece of shrapnel flew right into his grandmother's back. Of course,

he said, he didn't know it at the time, but even today, he can feel it

in the raised surface of her skin. He said all he can remember is grabbing

his little sister and running for the door on the opposite end of the

window, and how he tripped over his grandfather's body on the way out,

and fell hard, on his knees, and scrambled to get back up again. They

left the next week.

I suppose he didn't have to do much

explaining. He didn't have to explain to her what a shelling was, like

he did for me, he didn't have to talk about how it was a bomb that split

out into many, many pieces of shrapnel —the purpose to take as many

human lives as possible. He didn't have to describe the sounds of the

shellings he heard in his bed at night, or how the fear of the shellings

prevented him or his brother from ever going outside. How they stayed

cloistered in their apartment building, shuffling downstairs to the basement

for daily lessons from a retired teacher in the building. He didn't have

to hear me repeat "That's so awful, that's so awful, that's so awful."

The girl with the bent arm merely

looked at him, and he saw tears in her eyes, just barely noticeable on

the inside corners, because they caught the neon light. She breathed onto

the mirrored glass and drew the hospital in Sarajevo, all the beds lined

up like dominoes, and the shelling that caused a doctor to pull her arm

so hard, the nerves somehow got unattached. And then, she stepped away

from the mirrored glass, and struck the ash off her cigarette, and then

sat down on the edge of the sidewalk and took a deep breath.

He didn't know what to do, he said,

so he sat down next to her and he hugged her. She hugged him back with

the one arm, rested the other elbow on his shoulder, and leaned her head

against her forearm. And even though he swears there was no attraction

there, he leaned over and kissed her upturned cheek, like he was kissing

a sister, and her tears were salty.

III. Sour

Ten

For many years, I was afraid of flying. Then, one day, I almost flew.

Why I married a pilot in the first place, I have no idea—besides

the fact he once came down to the ground for four days every two weeks

and brought me little treasures from the places he'd stopped—like

a kokeshi doll from Tokyo. Or wooden clogs from Amsterdam. I still wear

those things today. The painted Dutch ladies are completely worn off of

the toes. Only their eyes remain. The hollow sound of them against the

cement of our front driveway reminds me I'm here on the ground, while

he's up in the sky.

So, anyway, today I packed up the

clogs into a little rolling suitcase and headed to LAX. You see, it's

our anniversary, an important one— the 10th. Ten is an important

number. It's the number of years before a first high school reunion, the

number of commandments God gave to Moses, the number of pins in a bowling

alley. It's not a number you miss, especially for reasons such as flight

schedules or layovers. In other words, a woman shouldn't sit in a silent

house on a tenth anniversary, waiting for the phone to ring.

I packed my bag and drove to the airport,

along I-10. The 10s of the highway signs taunted me every few miles. 10!

10! 10! They were my tanned, big-calved male cheerleaders along the way,

and as I saw each one I gripped my knuckles tighter around the steering

wheel. I was going to do this. The rest was a blur—long-term parking,

shuttle bus, departure ticket line, escalator ride, until I reached The

Tunnel.

I gave my ticket to the ticket taker,

and entered the portal, the birth canal, the entry into this other place,

devoid of air. I stepped up, only to be greeted by some bimbo stewardess,

I mean, flight attendant who smiled at me with her picket white teeth.

I thought to myself—"I am breathing in other people's sour

breath. There is no way out once they close us in. I will be in a Ziploc

bag, sealed tight until the red and blue make purple, with every bubble

pressed out with the palm of one's hand. The closing of that door is the

final cinch."

They gave me a window seat. I looked

at the Plexiglas next to me. It wasn't a circle, yet it wasn't a square.

It wasn't even a window, really. It was a false opening into the sky,

an illusion of escape. I pulled the seatbelt tight, the metal clasp sitting

heavy on my stomach, and gripped the armrests in my hands. I thought to

myself, "How many other sweaty hands have gripped these armrests?

How many others have imagined the yellow breathing masks falling from

the ceiling like octopus angels? And does anyone but me realize that they

can't be saved, that those things are there to strangle them, to wrap

their many suction-cup covered tentacles around human necks, to save them

from their own hysteria?"

And when the air had grown too stale,

I stood up, gasping for breath, clutching my carry-on bag and shouting,

watching those passengers walk backward in their clumsy, pitiful way,

stepping on each others toes, steering their luggage backward, shuffling

and mumbling to themselves. I rubbed my hair wild with both hands, and

shouted. It felt good to shout. It made me think maybe ten is not such

a significant number, it is only one more than nine and one less than

eleven. As I ran the reverse direction— out of The Tunnel, floating

up into that gorgeous brick chimney bringing smoke to the sky, I could

see the light of the souvenir shop. I opened my suitcase, and took out

the clogs, and set them on a shelf next to the shot glasses and spoons.

And I kept walking until those little eyes could see me no more.

IV. Bitter

Her Giant Face

Here's the deal. I went to Chicago on one of those "find yourself"

trips, the first vacation I'd taken from my cubicle job all year. I figured

if Roxy and Velma could become infamous in this town, I could find my

own piece of jazz. I was sitting in a pizza parlor, eating a piece of

Real! Chicago! Pizza!, and reading a hot pink flier that was handed to

me. It claimed that if I called a certain phone number, I could lose five

dress sizes in five weeks. I was thinking about this...how a teenager

can make a woman feel so bad about herself by simply passing along a piece

of paper, when I glanced across my table, out the window, and saw a large,

familiar face looking at me from the side of a skyscraper. I'm talking

large-large, huge—almost five stories tall. I almost gagged on a

thick, doughy piece of crust, that's how surprised I was to see my old

friend Barbara on an ad for some perfume we used to call "ode de

toilette" when we were just kids. Thank goodness my crust didn't

get lodged in my throat, because I've been trained to do a personal Heimlich

maneuver which involves flinging myself over a chair—it's not a

pretty sight, especially after seeing Barbara looking so beautiful, so

I was pretty thankful I didn't have to make a spectacle of myself within

that very hour. Instead, I walked casually out of there, pretending that

her face wasn't looming over me. I forced my gaze up the side of another

building, where a couple of window washers were at work. They dangled

by ropes around their waists, just one slick wall of skyscraper in front

of them. They had interesting techniques. It was unique and very intriguing

and made me forget all about Barbara and her giant face. It made me forget

so much that when I looked back across the street at her, I could only

make out a pair of eyes, a nose, a mouth.

You figure they would change the ads

on skyscrapers fairly often. Not this one. It didn't budge. Every time

I stepped out of my hotel room to take a walk in Millennium Park or head

to the Art Institute—the bland face of large features was there.

I could even make out the peachy-beige speck of a face from the Sears

Tower. Considering that cars look like ants from that height, we're talking

about something gigantic here. Here's what I figured: something this large

cannot be ignored. It must be acknowledged before it can be forgotten.

So, I went to the corner bakery and ordered an herbal iced tea with a

chicken salad sandwich to go. I grabbed the sack and found a comfortable

bench with a great view of what I now could recognize as, yes, truly,

Barbara's face. And as I ate, I made myself analyze her pupils, the curve

of her nostrils, her lips. Her head was held back at an angle, in a breezy,

casual way that has a whole busy life associated with it—jet planes

to Milan, a handsome millionaire husband, a chance every weekend to wear

a ball gown. I started to laugh, softly at first, chuckling at how ridiculous

it was. Because, you see, I know the truth—that we really are only

a set of features on a face. I laughed so hard, I choked on a chunk of

bitter walnut in my chicken salad and ran around behind the bench. I flung

myself over the top of it and gave myself the Heimlich maneuver until,

red-faced and exhilarated; I found that I could breathe again.

__

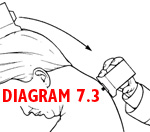

The word "Taste" brings me back to elementary school and the diagram of the tongue. That "taste map" always puzzled me, with sweet on the tip of the tongue, salty along the sides, sour further behind, and bitter way in the back. I remember sucking on a lollipop and rubbing it against one side of my tongue and then along the back, to experiment with this theory. The truth: it was sweet all over. I recently learned that the "taste map" is a myth. According to Wikipedia, it is "generally attributed to the mis-translation of a German text, and perpetuated in North American schools since the early twentieth century."

The characters in these stories are in relationships with people who only allow a taste of themselves, instead of their full selves. I attempted to explore these relationships in different stages, from first/young love to sexual/physical love, from married love to the post-marriage rediscovery of oneself. I guess this cannot really be defined as "love", but perhaps the pursuit of love. I think there is something so desperate, yet hopeful, about the attempt to taste another person fully, to strive to "get" their complete flavor, especially when the other person withholds it. I tried to capture the desperation, that hopefulness.