ANTARCTIC AESTHETICS: SOME NOTES

Jason Anthony

"There was a time when I dared not admit to myself how little refuge and sustenance art finds on this land... Now, what I love in this country is...what constrains any art..."

—Andre Gide, Amyntas

*

The Aesthetic Stem Cell

South of worldly things, south of Earth's endless exchanges of heat, Antarctica waits like an aesthetic stem cell. The continent sleeps. Ice is everywhere. Silence and light drift like clouds. Clouds hang cold and thin. Cold scratches at our face.

For eight austral summers, I approached the ice continent from the jet stream, landing in temperatures that did not change during descent. On the Antarctic coast, I spent my summers shuffling along the margin between northern oceanic life and southern terrestrial space. In the blank interior, over mile-deep ice, my notebooks filled with a scrawled dialogue between language and silence, between my little Something and a Nothing larger than China and India combined.

Living in various transient communities (from McMurdo Station's industrial science settlement of 1200 to isolated two-person field camps) around the continent, I felt the abstraction turn me inward, away from a landscape seemingly less substantial than the smallest attributes of mind.

A rare gift: We fly down to this local moon, drawn by our desire to gather data, and find instead the difficult roots of both landscape and the self.

* * *

In August, the sun arrives in McMurdo Station for the first time in five months. The polar halflight soaks into the distant glaciers of the Transantarctic Mountains for a few minutes, then a few hours per day; the aquarium colors of sky and ice mix with the most delicate colors of solar fire; tones of orange, raspberry, chrome, lilac and nacre drift like free neon over a subtle radiance of whitened slate. The ice absorbs, deepens the light.

These color words, however, are shallow. The crepuscular colors of Antarctic August must be imagined as filling the space between the eye and the horizon. The words I use are surface words, but the colors I describe have a depth of being. The air seems lit from within, like bright gas inside a bulb. Light emanates from the snow and ice instead of merely reflecting from it.

There is a luster to the ice that the Earth could not predict.

* * *

At the onset of my fourth summer contract (my friend Kathy's second), Antarctic weather frustrated our first two attempts to fly south from our deployment city, Christchurch, New Zealand. Both flights boomeranged. On one, Kathy and I and a hundred others cramped shoulder to shoulder flew all the way to McMurdo, circled over its storm we could not land in, then returned the five hours back to New Zealand. Above Antarctica, one porthole became a flashlight playing in the dark olive-drab interior of this military transport. Already zombies, we watched the bouncing light, a reflection of the full wedding dress whiteness of storm-sky below.

Then, above Christchurch, the same porthole became a pinhole camera, splaying silhouettes of buildings and trees against the ceiling of our fuselage. As if the place we could not reach were the source of all light, the living landscape we came back to the only possible subject of our imagination, the metal tube we flew in our camera, and we the film... And we spent ten hours for one wasted exposure.

* * *

"It is not that the land is simply beautiful but that it is powerful. Its power derived from the tension between its obvious beauty and its capacity to take life."

—Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams

Antarctica confronts us with the inherent threat of a landscape more resilient than life. To be made of flesh, and to possess a consciousness that knows the futility of flesh against this cold, is to be living in the moment of a dream in which beauty and death appear as a single seed. The depth of one's fear determines which of these, beauty or death, we believe contains the other.

I think of where the clean slate of the East Antarctic ice cap meets the Transantarctics, where the eye looks inward from the mountains to the great white emptiness. The landscape's power is beyond the verbal frame of metaphor. "Clean slate" and "great white emptiness" don't mean a thing. Language fails us. Only an abstraction like "nothingness" takes in the whole view, though that abstraction must also somehow express the transience of our presence.

A statement about the bright field of the Antarctic is also a statement about the passing silhouette of the self.

* * *

The ice holds its tongue (and ours) perfectly, translates all of its would-be colonizers equally on its preternatural ground.

* * *

Antarctic space is all that's left to explore on the planet. Somewhere beyond us are the interiors of invisible things, the blind ocean depths, and the hidden workings of sentience. All these destinations will reveal themselves to be as much features of the observer's consciousness as they are things in themselves, and are thus antarctic.

* * *

"Eternity ticks off the instant with the word." —Edmond Jabes, The Book Of Questions

When eternity is ticking instants, it is no longer eternity. Words, as Jabes suggests, may be either time or not-time, dislocations outside the ticking.

Words and instants relate similarly to eternity and deep Antarctica; they are parenthetical applications that, if conceived as whole and unfragmented, constrain their "contents" within false limits. The observation these parentheses allow transforms or effectively eliminates that which we measure. Antarctica is composed of identical instants shattered by words. Only by these fragments, however, can we see Antarctica.

*

Only Ourselves For Totem

Antarctica is the only major terra incognita ever discovered by Europeans. No native waited on the fast ice as the first wooden ships limped south. No culture predates us. The implications for art are both staggering and unrealized.

* * *

There is virtually no middle ground on the ice. The charismatic coastal landscape has in its penguins and stones a little perspective, as do the Transantarctic Mountains in the dense topography of glaciers and peaks. The vast bulk of Antarctica is flat and white, however, and between you and the distances there is nothing.

The rare examples of middle ground on the ice cap are composed by things we import to our campsites: fuel barrels, tents, snowmobiles, bamboo poles topped with ragged patches of cloth.

Usually, however, we surround ourselves closely with these imports, and beyond them the verifiable world ends; everywhere else belongs to the thin bleached line of the horizon.

When I walk away from a camp into Antarctic space, the camp slips suddenly from front yard to distant hamlet.

* * *

"Stretched out, vertical

simultaneously outside and inside at the four points of the compass

withdrawn

yet in the Infinite..."

—Henri Michaux, "Yantra", in Darkness Moves

At the South Pole, we claim to be at the endpoint of a sphere. And it feels that way: The farthest outpost of the familiar, the flat disc of empty space curving away from it, and the overarching perception of extremity that somehow says all routes of departure take us home.

We come full circle when we take this singular piece of geography and isolate it with the same imagination we used to create it.

* * *

No ravens or wolves moving their dark bodies quietly over the lit plains. No bears roaming the sea ice for fat-rich seals. No men in kayaks slipping around difficult ice floes in search of penguins.

No hunters borne from these shores. No animals anywhere but on the watery fringe. Antarctica offers no mythic figures from its antibiotic elements. We who have recently arrived have only ourselves for totem.

* * *

A world of meaning

before meaning.

Still we think

something waits.

* * *

Kathy, a tall blonde troublemaker who gave up social work to labor in Antarctic waste management for a few summers, always grumbled about our wasted lumber. The United States Antarctic Program discards tons of pallets, crates, dunnage, 2" stock and plywood every year, rather than setting it aside for reuse. She and her crew would grind the wood up and ship it back to the U.S. for use as fuel, usually after only a single use.

A recovering Catholic, Kathy's response was to use the wood to build crosses, monuments to itself. Over one McMurdo summer, she made dozens of small ones, surrounding the wood grinder. At the South Pole the next summer, she planted a forest of tall crosses around a towering pile of debris. Kathy came from the Cascade Mountains of Washington, and so had borne witness to both ends of the epic journey these wood products made from subsidized American clear-cut to subsidized Antarctic outpost. As if rebuilding the trees, she stood up larger and larger memorials in the snow, up to twenty feet of beautiful metaphor looming over the dead end of Earth's cargo line.

* * *

Kathy and I, early in our Antarctic lives, flying low over the fractured pack-ice, eager faces glued to the LC-130's small portholes, viewing the lay-out of a jigsaw puzzle larger than most nations. The square-edged polygons of the ice resemble a child's map of the Plains states. "Kansas!" she says, pointing left. "Colorado!" I say, pointing right.

Amazing what the mind uses to map out its new home. Nebraska becomes what I imagined as a kid: isolated snowy flatness within black borders.

Whales visible among the floes like bison...

* * *

The land without pentimento. Under our few scratchings and daubs of residence there are no others. A century of exploration and pinpoint occupation put a few swatches of bright color (the colors of come back and come-find-me) in the margins of the continental canvas, a few dots and dashes for our machines' songlines across this yet-unpainted still life, and one small bold period in the center, at the Pole of Perspective.

* * *

"The land is like poetry: it is inexplicably coherent, it is transcendent in its meaning, and it has the power to elevate a consideration of human life."

—Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams

The ice is like a syllable: it is inexplicably coherent, it offers only fragments of meaning, and it has the power to suggest the absolute reduction of life, and of the poetry of life.

* * *

The elements of art are not art themselves. They are both too constrained and too powerful in their expression. Antarctica is a source; it is from elemental platforms like these we go forward to make art, to act upon the cold creation we have witnessed.

* * *

No reason to live,

I'm afraid.

Tight as a moon,

one cold seed

binds one blind root

to a hollow sky.

How did it begin,

this bright Pole,

to move my compass?

* * *

I lean so far into trying to understand this place that I feel encumbered by it, interrogated by it. I've entered a natural history that finds no metaphor in my physical self. Antarctica, in its blankness, demands imaginative personal answers, even begs such questions that insist on self-reflection.

*

Strange Fates

Kathy and I are two of the actors in our friend Nicholas' movie. Plied with whiskey after brunch each Sunday, we put on his homemade masks and headed outside to trudge (me) or prance (her). The Strange and Terrible Fate of Sir Robert Falcon Scott is a brilliant 20-minute Dadaist revisioning of Scott's 1912 fatal expedition to the South Pole.

Three figures, one Scott and two ponies, each signified only by the two-dimensional mask worn deep inside our fur-lined hoods, march in line across the ice, carrying a rock-filled suitcase and journals to record the experience. First one, then the other pony is chased down and symbolically eaten by the starving, scurvy-ridden Scotts. Each pony then becomes a Scott, scribbling by mitten in his journal, adding rocks to the suitcase.

Three Scotts stumble onto the (bamboo) Pole, and begin their wearier stumble home. (I also did a cameo as the blithe and distant Roald Amundsen, the successful discoverer of the South Pole, jogging across the whiteness dressed in a red- and black-striped tracksuit.) One by one the Scotts drop, as the survivor(s) observe and scribble. As the last Scott lays down his journal, throws an arm over a frozen twin, and gives up his ghost, the wind flips the pages.

It is a silent film, thank god. Too many words sail down to the Antarctic from armchair adventurers to argue the pros and cons of Scott's story. Nicholas is a local, and filmed out of the silence that fills the icescape. This silence, which was Scott's judge and grave, still has much to say.

* * *

Here we are, full of meat and promise.

* * *

We arrive shackled to our northern ideas of art evolving out of complexity. Antarctica reminds us instead that art falls out of silence.

* * *

Of the six roommates I had in McMurdo over the years, three made art obsessively. For two summers, Nicholas (www.bigdeadplace.com) and I talked and scribbled, scribbled and talked, as we followed our various Antarctic obsessions with notebooks and cameras. Berndt (http://members.tripod.com/~savig/index.html) painted day and night, stacking nudes (on canvas, plywood, barrel lids, whatever he could find) four-deep against the walls of our room. And Galen quietly contributed centerpieces (an electric chair decked out like a throne, a full-size human figure sculpted out of discarded wires) to the annual MAAG (McMurdo Alternative Art Gallery—http://maag.60south.com/) shows.

The MAAG show is a station party thoroughly disguised as an urbane and ironic art gallery opening. From do-it-yourself blowtorch ice-sculpting to homegrown surrealist performances, the MAAG gives residents another reason to drink and generally forget about the Antarctic. The art is sometimes brilliant, but very little of it relates to landscape or "the dialectic between idea and ice" (Stephen Pyne). Like us, it mostly looks inward or northward.

That said, however, the most beautiful work of Antarctic art I've ever seen was a snapshot of Kelly, tacked to an out-of-the-way office wall during a MAAG bash. Blonde, pretty, intensely social, Kelly was a Florida party girl with little patience for the cold. Kelly liked to be naked. Kelly also liked to quietly and intelligently multitask; she worked up budgets and reports while handling a constant flow of radio chatter. Above all, Kelly—an Antarctic resident, like the rest of us—liked a challenge.

Beer in hand, I stood with mouth open and heart beating as I stared at the MAAG snapshot. Secretly, Kelly had convinced a remarkable underwater photographer (who shall remain unnamed because of possible safety violations) that she could, on a single breath, submerge herself below the three-meter-thick sea ice and hold steady long enough for him to frame and focus his picture. The photographer dove a hundred feet deep and positioned himself face-up. Nude, Kelly clung to a weighted rope that quickly plunged her twelve feet under. Nude, in 28° F water, she let go of the rope and floated happily under the endless blue skin of the ice.

* * *

We are trashing the Antarctic, of course. Despite my best efforts, wind has ripped plastic from my hands and paper from my camps, while petroleum dripped from every machine. Hundred of temporary settlements across the continent have left their stain and debris during fifty years of nomadic science. Forests of now-buried bamboo poles line forgotten landing strips. Permanent coastal bases, like McMurdo, have deeply scarred their neighborhoods, spewed sewage and toxic chemicals. Inside the ice cap, deep wells of forgotten cargo and sewage lurch along glacial paths toward the coasts. Residuals from roughly five million gallons of burnt diesel fuel sprinkle down each summer from American intracontinental flights.

Bases are much cleaner and friendlier now—dogs, for example, once fed with seal carcasses, are banned, while fuel spills are fewer and smaller—but we still assume that some pollution is a small price to pay for good data.

Yet very little of this damage matters, except in the way of aesthetics. The amount of real estate occupied by all bases and camps together is miniscule. Moreover, as we darken and bulldoze in progress-driven exuberance, there is little to kill. Where we pound stone or snow, we might as well be pounding sand.

The great environmental changes being wrought in the Antarctic are done by the geopolitical entities that have sent us south. Global warming is the hot knife that now slices through the ice shelves and coastal glaciers. Ozone depletion and over-fishing are doing to the bottom of the Southern Ocean's food chain what European whalers and sealers did to the top in the 1800s.

Whether we defecate on the snow or delicately pipe it under the ice, it is just a drop in the frozen ocean. It's not nice, or intelligent, or particularly advanced for an advanced science-based society to pollute our beds here, but the source of Antarctic transformation is the world, not its outposts.

* * *

The white stem and black stem.

The white stem and the black stem

interrogates it.

*

Human Weakness

"...concepts such as soul and sanity have no more meaning here than gusts of snow; my transience, my insignificance are exalting, terrifying. Snow mountains, more than sea or sky, serve as a mirror to one's own true being, utterly still, utterly clear, a void..."

—Peter Matthiesen, Nine-Headed Dragon River

Do these West Antarctic nunataks (the peaks of ice-drowned mountains) offer a mirror for the human soul? These beautiful stone outcrops, scattered like an archipelago across the ice cap, seem an embryonic notion of form in a plane and time that has outstripped form with formlessness. These peaks are both unswallowed and unrevealed. The ice will surmount them, the ice will fall away. In this respect, at least, they mirror the human presence, our transience.

If these darkened lighthouses are being ground up by the glacial flow of the ice sheet, then who am I, and what good are these faint footsteps and rough breath as I climb a few hundred feet to claim perspective on a landscape of emptiness, dotted with the remnants of what is not yet void?

The void keeps me conscious, though it is a consciousness, in its ideal form, which seeks its own demise.

The few lichens here, mere kisses on the stone, contain all life. Yet they are close to nothing, just the suggestion of life. And there is our mirror, exalting, terrifying.

* * *

Only when I write do I play with doubting the place of this hypothermic continent in the flow of life. Out walking, listening, there is no doubt. The silence is alive, deafening. Everything is in motion, albeit imperceptibly, and with such an immense, tectonic pause in its music that I find myself lost in between two notes I may never hear.

* * *

Unwilling

To be warmed by a single thought,

Small sharp snow

Makes my bed soft,

Just lay down,

Cold my blanket, ice my pillow,

With horizons as wide as arms,

Arms without a body to hold them.

What's left to think? What wind blows

White teeth across my feet?

* * *

Infinitesimal ice crystals—called diamond dust—fall like the ghosts of punctuation, or sparkle like the lit symbols of mathematics. We who stumble amid the glitter look for ways of making stories out of the ellipses and formulae that are this continent's only blossoms.

* * *

"I have brought nothing with me of what life requires, so far as I know, but only the universal human weakness."

—Franz Kafka, The Blue Octavo Notebooks

I travel to explore, but to explore not so much a place as the space between the place and me. There are absences (in life, love, and death), and then there's Antarctica. I have no idea which is the better metaphor for the other.

The aesthetic task lies in fulfilling the Antarctic metaphor. The knowledge will come from poetic fragments, if it's possible, and more generally from a greater literature that feeds off the interior. Very little of this admittedly esoteric understanding has been acquired so far, and even less has left the ice to explore the world.

* * *

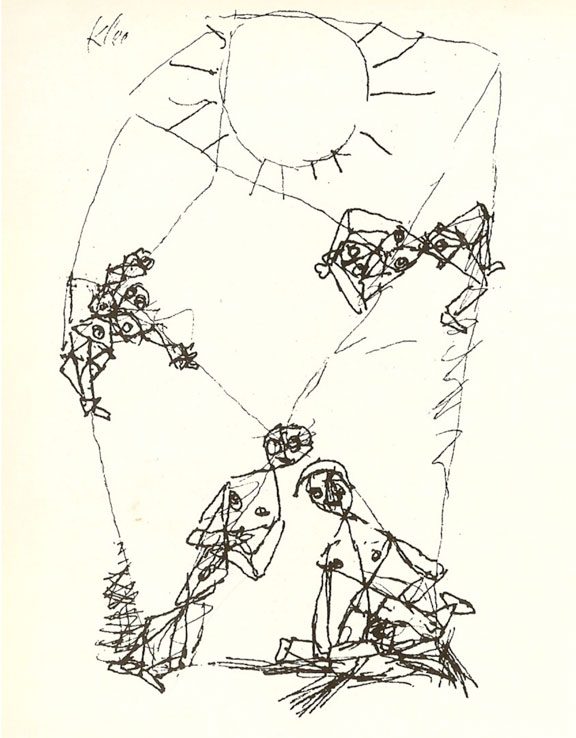

Paul Klee's ink sketch "Human Weakness" (above), dated 1913, shows four figures trapped in allegorical postures against the inside wall of a rough rectangle, which also barely contains a large crude sun. The figures are pinned at the corners of lines that brace the contained whiteness; three men are on their knees, two of them beating at the walls, just below the sun. The fourth man may be a corpse. The frame resembles a schematic of a weathered tent.

Without proof, I've come to think of the sketch as an elegiac window onto the end of Robert Falcon Scott's concurrent Antarctic Terra Nova expedition, the disastrous mission made against this empty solar no-man's-land. It seems also like a 20th century tarot card: The Failed Quest, perhaps?

News of the deaths of Scott and his party reached Europe by the end of 1912, fodder for the panegyric press and the lyric arts. A collapsed tent with three frozen bodies (the fourth had crawled off to die), found half-buried in the Ross Ice Shelf, became a British—and to a much lesser extent, European—symbol of desperate courage. Scott's Pole of Ambition was laundered into culture's Pole of Tragedy. I like to think that Klee saw through the British apotheosis to the dark meeting of hope and unforgiving nature. There are no heroes in the sketch.

* * *

How do I say goodbye to a place that never acknowledged my existence? With wonder and ignorance, I suppose, the same brushes I wielded upon arrival.

* * *

The true journal of this time made by my shadow as it passed over the ice. In a word, nothing. And I remember it well.

__

The essay plays mostly with the "empty" aesthetics of the Antarctic icescape, partly with how we occupy it. If you want to read up on the real deal concerning our occupation of Antarctica, read Nicholas Johnson's Big Dead Place (Feral House, 2005) and check out his [website].

Klee image used courtesy of the Klee estate.