|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen |

Literary Plot

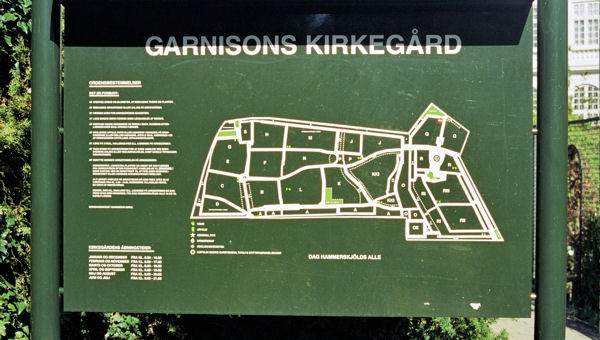

Selecting a place to be dead: Garnison's Churchyard, Copenhagen

Essay and Photos by Thomas E. Kennedy

“I am going to Llangodoch to be buried… The ground is comfy in

Llangodoch. You can twitch your legs without puttin' them in the sea.”

“But you're not dead yet, Mr. Thomas. How can you be buried then?”…

Grandpa stood firmly on the bridge…and stared at the flowing river

and the sky like a prophet who has no doubt.

-Dylan Thomas, “A Visit to Grandpa's”

Lady Alice and I feel it is about time—we are 131 years old, put together—so we set out to select our gravesite. We have long ago agreed on our cemetery—the three and a half century old Garnison's Churchyard in eastern Copenhagen, which King Frederick III established in 1662 as a burial place for the Danish army, located just outside the eastern gate of the city walls. Gate and walls have since been deconstructed; near where the gate was now stands the East Gate (Østerport) station of the city train, but Garnison churchyard flourishes still, a cozy green place to tuck yourself under the dirt for the first part of one's eternal peace.

Welcome to the graves

No longer limited to the military, Garnison now houses the remains of a variety of corpses; in addition to 23 generals and their generalesses, many admirals and admiralesses, colonels and colonelsesses, there are scientists, artists, businessmen, spiritual leaders, politicians, writers, sculptors, doctors, bishops, a Nobel laureate, lawyers, psalm authors, a cartographer, judges, greengrocers, economists, insurance men, bankers, the first Danish author of young adult novels, ballet dancers, the founder of the Tivoli Gardens, even the mistress of King Frederik VIth, who bore him four children, all

endowed with noble titles. Perhaps there is also a place here for an American expatriate writer and his Danish writer-artist partner!

Thoughts high and right

Among the notable residents are the artist, René Poul Gauguin, who died in 1976, nephew of the great French artist played by Anthony Quinn in Lust for Life, as well as practitioners of the art of war such as Major General Olaf Rye, who fell leading a long, hard battle that Denmark won against the Germans in 1849. Gauguin's gravesite is decorated with one of his own arguably abstract sculptures (it has been pointed out that by closing one eye you can clearly identify it as a stag beneath a tree), Rye's with a realistic bust of himself by the great Danish sculptor H. V. Bissen (1798-1893) and a memorial verse by the Danish poet, H. P. Holst (1811-93):

Gauguin's nephew's grave is marked by one of his sculptures, arguably abstract, but look closely and you will see a stag beneath a tree. Behind the gravesite is the Russian Embassy

Beat in his heart.

Under his gray hair,

A warrior's might

If he retreated,

Always with honor.

Charging to battle,

Triumph in sight.

(Translated by Thomas E. Kennedy)

There are many graves decorated with the work of artists—Ernest Eberlein (1911-93) by his own graceful sculpture of his wife and daughter; Missionary Rasmus Buch Clausen, who waged his inner mission for decades against drink and prostitution, with a life-sized bronze by August Hassel.

Major General Olaf Rye who fell defending Denmark against the Germans in 1949. The bust is by sculpture H. V. Bissen, the epitaph by poet H. P. Holst

The resting place of artist Ernst Eberlein (1911-93) is marked by his own sculpture of his wife and daughter

Here lies—or stands and thunders—a priest of the “Inner Mission,” Rasmus Bach Clausen, who dedicated his life from the 1880s to 1904 to preaching against the evils of prostitution and drink. The life-size bronze is by August Hassel

Perhaps, I think, we should not lie too very close to Clausen.

Because Lady Alice and I found one another late in life—we've only been together for a decade—we have decided to remain united forever. Or for at least as long as Garnison continues to exist. According to current Copenhagen city ordinances, it will continue until the year 2150. I worry a bit about what might happen to us after that. “But,” the sympathetic graveyard director, Klaus Frederiksen, assures us, “in a few years that time limit will be extended, as it has been continually for the past few centuries. Garnison will always be here.”

A cemetery in Copenhagen is nothing like a cemetery in the United States or in any other city I know of, not even Paris's Père Lachaise (which anyway is not particularly green). I've never once visited the graves of my father or mother other than on the days they were buried because their cemetery, like so many of its sort, is so out of the way and poorly appointed, surrounded by a very uncharming chain-link fence and plotted out like an overcrowded chunk of urban sprawl. Copenhagen cemeteries—particularly Garnison—are green and inviting and in media res, with benches where people are welcome to sit, sunbathe, read the papers or a book, eat a sandwich, even drink a bottle of beer, lie in the grass, walk the dog, take the little ones for a Sunday tour, even share a passionate kiss.

Garnison is green and inviting, with benches where people are welcome to sit, sunbathe, read the paper or a book, eat a sandwich, even drink a bottle of beer.

I moved to Denmark thirty-three years ago and already knew three years later that I wanted to be buried here, though I did not yet know it would be with Lady Alice. What I knew back then was that this was a green place, that even if it started as a military cemetery, it is decidedly unregimented, irregular in its outer perimeter and within it, a patchwork of sections and scratch work mix of staccato paths where a person can easily get lost—or lose himself in the contemplation of 3½ centuries of the history of the place, the lives gone by: the 23,000 Copenhageners who died of the pest between the summers of 1711 and 1712, and the seventeen prisoners who were set free in return for burying the pest-infected corpses here, only two of whom were still alive a year later (presumably the fifteen deceased ex-cons were also buried here), the 538 cholera victims of 1853 and the 746 burials in 1864, the year of the war with Prussia. Or the fact that the top German general, during the five-year occupation under World War II, lived in a mansion alongside here—an area once dedicated to a dog cemetery, later commandeered by an extremely wealthy family to build their castle, second only to the King's, and now housing the Danish Red Cross. The cemetery is bounded by the embassies of Egypt, Spain, Britain, the U.S and Russia as well as the ambassadorial residency of Canada. It was not planted inside the city, but rather the city—this section of the city—grew up around the cemetery, shaping it, giving it the pleasingly asymmetrical contour it enjoys today—half a kilometer across but affording no unobstructed view from end to end.

Until the Velvet Revolution, Garnison served as a green buffer zone and symbolic barrier between the Soviet and American embassies here in Copenhagen, which are separated by about a 250-meter stretch of beech trees, willows, pines, yew hedges, yew trees, magnolias, cypress, lillies, aranthis, crocus, snowdrops, and a variety of 200-year-old trees growing from a scattered patchwork of gravesites commemorating the lives of a tremendous variety of people. During one period, there was a Chinese restaurant owned by people from Peking just across the boulevard, forming a nearly unilateral triangle with the Soviet and American embassies, while the zigzagged path that runs behind the cemetery from Bergen to Castle streets is known as Ho Chi Minh Trail. It was delightful to sit on a bench in that pure green resting place and smile over the foolishness and electronic connections tangling between the basements of those three structures.

Three hundred forty something years ago, cows grazed outside the palisades and ditch that demarcated one side of the churchyard; the other side was formed by the waters of the north harbor until a couple of kilometers of landfill was dumped in. According to numerous reports, the grazing cows sometimes forced the palisades and found their way across the ditch to nibble the grass that grew on the then still stoneless gravesites—not until the mid-19th century did families begin to erect and engrave stones to commemorate their dead.

Behind the green foliage sits the US Embassy

For thirty years, Lady Alice and I worked together not a hundred meters from here, in the Domus Medica, and frequently strolled in Garnison at lunch time, on our way home after work, alone at first, now together. What better place to share our last apartment? She hooks her wrist into the crook of my arm as we proceed to the offices of the churchyard director, Mr. Klaus Frederiksen. He leads us on a tour of the premises to show us what is available to us: We may choose between a classic burial plot or the different types of urn placements. We may choose a hedged, three-square meter plot that accommodates one coffin and six urns or any multiple of that (six square meters with two coffins and twelve urns, nine square meters with three coffins and eighteen urns, etc.) Or we may choose an unhedged four-urn place in the crocus area over against the southern wall with or without a lying stone that has room only for four names to be engraved, or a plot with a waist-high stone pillar and place for four urns around it. The stone pillars have a concrete look and seem to me to resemble the low-priced housing south of Copenhagen. They also resemble concrete beehives, all in a row. I would not be happy choosing this as our final home. I would not be happy offering to share this with Lady Alice.

Back in the offices when we learn the price of a six-square-meter plot— $35 a year—and the fact that, unlike with the urn places, we may tend this ourselves, we know that this will be the place for us. We will also have to pay a nominal one-time fee for a hedge around it—and of course, on top of that, the cost of the stone. But still, at that price, I am inclined to reserve a plot for the next century. Why not?

We walk out arm in arm to scout for an appropriate spot to be dead, discussing how we will decorate it during the years we are still alive..

“We could have a forsythia hedge around the plot perhaps,” I suggest. I love forsythia.

“Or,” Lady Alice counter-suggests, “We could have a yew hedge with a small forsythia bush in one corner and a tiny weeping willow or magnolia in the other.”

I have to admit this appeals to me. “And a small stone bench,” I say. “So whoever survives the other—you most likely—can sit and read poetry to whichever of us is buried—me, no doubt.”

“We could plant timian, too,” Lady Alice says. “It smells so good. While the plot is unoccupied, we could plant potatoes, too.”

“Are you sure?”

“Why not?”

“Who would eat potatoes grown in a graveyard? Or even timian for that matter. I mean…think of what would be fertilizing them.”

“The timian would be just for the scent.”

Plot RIII.8.1: Our possible final apartment

“Fair enough. But no potatoes, right?”

She shakes her curly blond head. “No potatoes.”

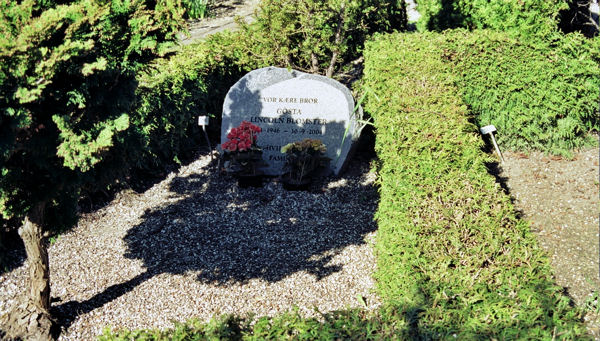

Wandering about we find a vacant six square meter plot. It is identified by a small tag on a stick jabbed into the earth: RIII.8.1. Our future address perhaps. I glance at the names on the grave to either side. To the left is Gösta Lincoln Blomster, born April 1st, 1949, deceased September 30th, 2004; to the right is Michael Lund, born June 3rd, 1922, deceased, March 27th, 2005. They seem like nice neighbors. “Blomster” means “flowers” in Danish. I wonder why he died so young? Surely he would like to have company. I like the name Lund, too—it sounds warm, it sounds like heather.

Our possible future neighbor: Gösta Lincoln Blomster

“What do you think, honey?”

“I don't know,” she says. “What do you think?”

“I think we could spend a lot of happy hours here together.”

Lady Alice catches my eyes with her blue smiling ones. “Me, too,” she says, and I can see we have no doubt.

On such a bench, Lady Alice will read poetry to me, or I to her, as the fates decide

Bibliography

Larsen, Hans and Mathiasen, Anders-Peter. Who's Lying Where, Walks in Copenhagen Graveyards (Hvem ligger hvor, Ture på Københavns Kirkegård). Copenhagen: Politikens Rejsebøger, 2001, pb (in Danish)

Olesen, Peter; de la Fuente Pedersen, Eva; Gram-Andersen, Jesper; Kjær, Gitte. Garnison's Churchyard, Historic Impressions and Churchyard Art (Garnisons Kirkegaard, Historisk indtryk og kirkegårdskunst). Copenhagen: Garnisons Sogns Menighedsråd, 1998, cloth (in Danish)