|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen |

Watch Out for the Hippos, Mr. Kennedy !

"The lion still stood looking majestically and coolly toward this object that his eyes only showed in silhouette, bulking like some super-rhino . . .

Then

—Ernest Hemingway, "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber"

We will be two days here in the main camp, touring in a jeep, three days in a bush camp, tracking on foot, then the final day back in the main camp to celebrate — perhaps to celebrate that we are still alive, if indeed we are.

We set out in the jeep – an open truck really with a roll bar (no doubt in case of being turned over by a mad rhino, I think facetiously) and a seat mounted on the left fender in which the tracker sits to watch for game. Soon — much more quickly than I expect — the tracker's hand shoots up, the signal that he has spotted game, and he says, “N'goni.” N'goni, I learn, is the Xitsonga for lion. And I see that we are already closer to a pair of lion than I ever expected or wanted to be. It occurs to me that if I had been on a safari with Ernest Hemingway, and he heard me thinking such things, he would have considered me beneath contempt, not even worth mocking in fiction. Of course, I carefully conceal any sign of fear from my children, lest I surrender my tentative hold on patriarchal authority. The lion seem unimpressed by us. The lioness rolls onto her back, exposing her belly, as if to invite a scratch.

“We're fine in the truck,” says Brendan. “In the truck, we're a large dangerous animal to them. They respect us. But if you separate from the truck, even stand up or stick your hand out, the lion will see you for what you are.”

Brendan enquires about my constant note-taking as he tells about the vegetation and animals and insects. I explain that I'm a writer, and he lights up.

I am wondering what we do if an animal sneaks up behind me, last in the flank, wonder whether that is a dumb question, remember African movies — King Solomon's Mines no doubt — where the last bearer in a flank is suddenly picked off by a hungry cat and goes down yelling, “Aieee…!” One of the cast's expendable characters, good for a shudder of blood lust.

I glance at Jesper. His eyes seem to reflect my thoughts: We're meat.

Next day we stay in or very near the jeep from morning to evening, which suits me fine. It seems we are concentrating on less dangerous game. We see a cut-throat finch, blood red feathers topping its breast, and a brown snake eagle circling overhead and a yellow-faced little bee eater, green coat iridescent in the sun. We see the hole of a baboon spider, big around as a fat plum and sheer as polished pipe; Brendan pours water down the hole, but the spider does not emerge. We hunker down in whispering silence by a jackal pup asleep in a drain pipe which Brendan asks us not to tell about — otherwise the others will come to see it and frighten it and it might run off from its mother who is out hunting for her pup's food. We see bush babies and vervid monkies, waterbuck and zebra, a wild dog with spotted hide and big ears sticking up from the grass.

“Will they charge?” someone asks.

The bush staff consists of cooks and trackers and, of course, ranger Brendan. We dine in a mess tent, a canvas overhead mounted on four poles, a wood platform for a floor beneath our canvas chairs. We are served by Moses, who has cooked on an open campfire off behind us.. Brendan eats with us beneath the canvas ceiling. After he has served, Moses joins the black staff to eat seated on rocks and vehicle running boards around the cooking fire. I ask about that, and Brendan tells me, “They prefer to. Sometimes they invite me to join them and laugh because I use a fork instead of my fingers.”

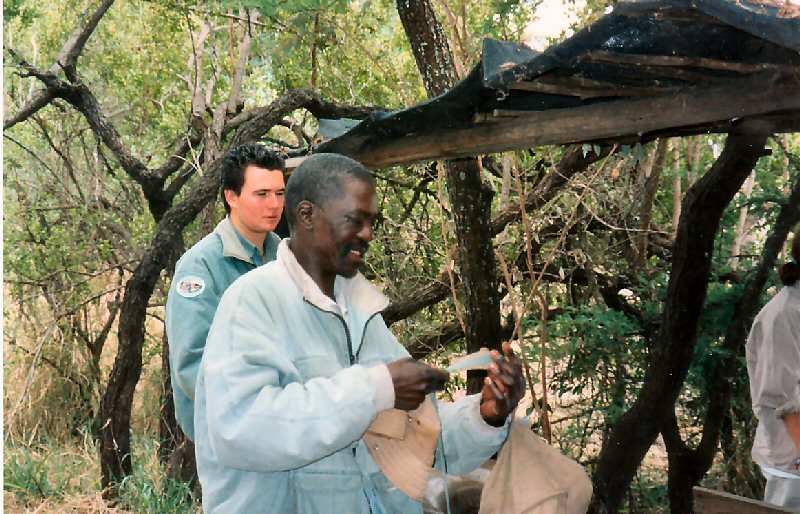

“Can I try that?” Brendan asks and takes the slingshot, loads it with a stone and draws back the rubber sling. Suddenly he turns, aiming it at Alfus' leg. Alfus chuckles. At the last moment, Brendan swings away and fires his stone at the wooden water tank. He hits it but the rubber sling recoils, smacking his hand so he yelps and drops the cattie. Alfus chuckles again and retrieves the weapon as the ranger cools his stung fingers in the air. Alfus loads and fires at the trunk of a tall slender tamboeti tree. The stone whacks the bark, chipping it. He quickly loads and fires again, slicing off a cluster of ticking seeds that fall and lay twitching on the earth, eager to release their blood-sucking larvae.

A Short Happy Safari in South Africa

Essay and Photos by Thomas E. Kennedy

. . . he saw a man figure detach itself from it . . ."

After two hours in a sweaty, dusty, banged up SUV from Pretoria airport to the Honeyguide camp, I snicker when the woman in the check-in tent has us sign disclaimers that we will take no legal action against the camp in the event that we are mauled, killed or in any way injured by wild animals. It was my idea that this area outside of Kruger Park in the northeastern part of South Africa would be a kind of variant of Disneyland, a realistic one, but not to include mauling animals.

We are instructed sternly never to return alone in the dark from mess to our sleeping tent without being accompanied by one of the rangers — there is danger of encountering an angry dugger boy buffalo. I begin to wonder whether I have been wise inviting my teenaged daughter and son along. Settled in my tent a few minutes later, I hear our travel companion — a six-foot-four-inch 200+ pound Dane named Jesper — holler in alarm that an elephant has stuck its trunk into his tent flap — and I begin to suspect this was not a good idea at all.

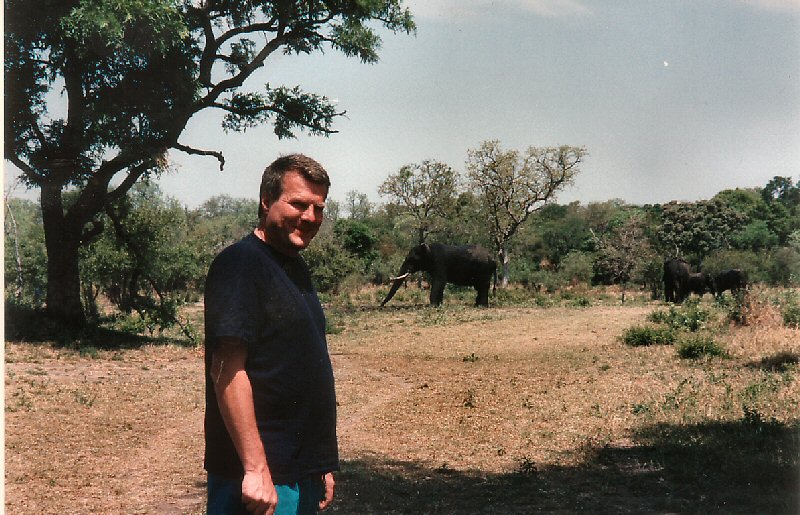

Our travel companion, Jesper, in front of the elephants who have discovered an underground water supply running through plastic pipes into the camp

The remainder of our first afternoon there is spent relaxing in the sun on the edge of the little pool, our bare feet dangling in the cool water — Jesper, Daniel and myself — drinking bottles of Castle beer and watching half a dozen elephants busy at something or other just outside the camp in a clearing some sixty meters away. One of the elephants is leading the others in some sort of game of tear up the earth with your trunk. Isabel wisely decides it is too hot in the sun and chooses the shade of a little lounge lean-to alongside the bar, drinking tea. Early afternoon by the pool is thirsty work. We three men, ranging in age from 17 (Daniel) to 52 (me), take turns fetching fresh rounds of cold Castles from the bar. After a couple of rounds we figure out why the elephants are digging into the loose earth with their trunks. One of them gets hold of something and steps backwards, tearing it from the ground. A plastic water pipe. Who says elephants are dumb? These ones have figured out that water flows into our camp through buried pipes. Apparently they've decided that if they get hold of the pipe and bring it home with them, they will have a ready steady supply of the wet stuff. They go running off, following their clever leader who has a couple of yards of water pipe tucked into his trunk.

“Think they'll elect a new leader when they get back and find out the water didn't travel with the pipe?” Jesper wonders aloud.

“Want another Castle?” Daniel asks. A neat row of empties along the edge of the pool informs me this will be our sixth. My 17-year-old son appears to be perfectly sober. I feel like a bad Dad.

“Daniel,” I say. “How in the world can you drink that much beer?”

He tilts his head quizzically. “Am I not your son, father?”

We sleep well that night after a succulent meal of antelope stew washed back with South African cab, each of us alone on crisp clean sheets in his or her tent, listening to the sounds of the jungle night. Bird cries, the WA-hoo! WA-hoo! of a baboon followed by the silencing grunt of a dog leader, the almost subaudible crunch of elephant and buffalo stepping quietly through the bush around our tents.

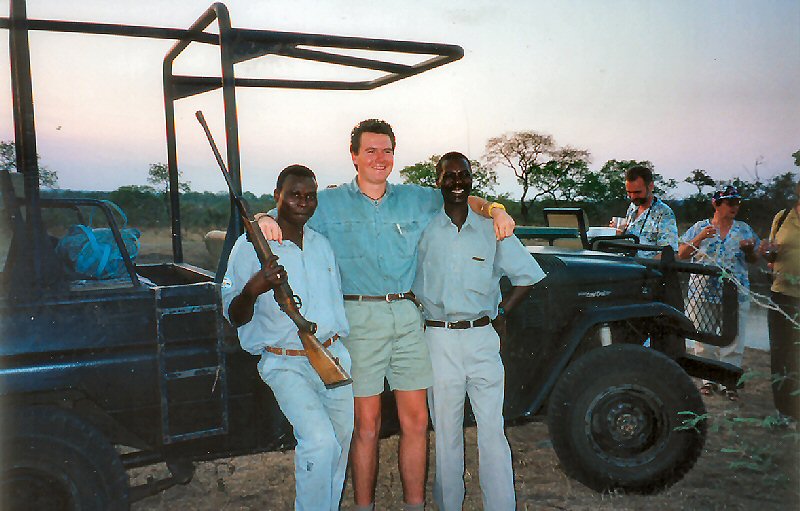

In the morning we are up early for a breakfast of eggs and warthog bacon and out in the jeeps. Our ranger is a 21-year-old named Brendan from Johannesburg, working for the summer to earn money for his education. He is aided by a tracker named Alfus and equipped with a rifle. If he fires the rifle, he tells us, he will lose his job because that will mean he has led us into danger. This sounds to me like text-book logic; I would prefer to know that he would not hesitate to use the rifle if necessary.

Our ranger, Brendan, flanked by two trackers. According to the hierarchy of the camp, trackers are not allowed to hold a rifle. The ranger could lose his job for this breach

Lion and lioness

Indeed, I think, remembering the short happy life of Francis Macomber when the point of view shifts to the lion's, who sees Macomber clearly only when he is out of the jeep. The way I feel at the moment Macomber was a pillar of courage by comparison.

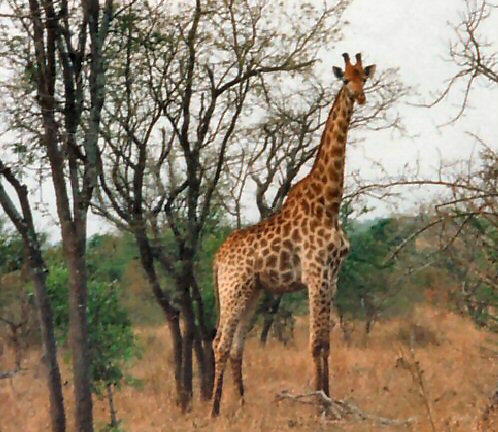

Next there are grazing rhinos, curious giraffe, thirsty lion sipping from a dam.

I grow bolder, seeing that the animals may glance curiously at us but seem basically unaggressive, disinterested mostly.

Brendan parks the jeep by the dam so we can stretch our legs. Daniel steps into the tracks left by an elephant that had been there before us for a drink — the print is thigh-high on him.

Curious giraffe

Daniel in an elephant's tracks

“I was named for a writer. An Irish one. My parents didn't have a name for me because I was unexpected, you know. Not planned. They were going to take me home from the hospital without a name but there was an Irish nurse there who said that was bad luck. She suggested 'Brendan.' The name of a great Irish writer, she said, who had died just ten years before.”

“Brendan Behan,” I say, touched by his openness and trust.

“Yes! That's who! And you're a writer. I'll do my best to make the safari as interesting as I can for you!”

Not too interesting, please, I think as he proceeds to lead me to a magic guarri tree, explaining what a good friend this tree is: sprigs of magic guarri placed close to the food keep the flies away and can also be used to swat them off in case that doesn't work. The wood is perfect for a cattie — a catapult, or slingshot — and the ragged edge of a magic guarri twig is perfect for brushing your teeth in the bush.

“Trees are the kindest of the earth's creatures,” Brendan tells me. “They stand and wait for your need and let you take without complaint. They feed the elephants and impala, the waterbuck, kudu, giraffe, and give a place for the leopard to drag her prey.” He points to the chipped bark of a tree. “See chere, a leopard climbed up with her kill. See how the bark is chipped away by her claws.” Then he turns and gestures toward a rocky rise, a weeping werbie tree, explaining how it provides seats for the baboons among the rocks and how the baboon eat the werbie fruit and in turn scatter the seeds in their droppings.

His eye catches something and he turns to the dam where a hippo floats, face just above water while an ox picker bird cleans its snout. “That cher hippo is called Sapo,” he says. “He comes up and wanders about at night for vegetables to eat. One time a woman — a nurse, a white woman — tried to beat Sapo on the nose with a broom because he kept stealing her carrots, and just as quick as that, Sapo jumped forward and bit off her arm. Hippo look slow but they're fast.”

I gauge Sapo to be about 150 meters out on the dam and wonder how fast.

Halfway into the meadow alongside the dam, Brendan shows me a dead leadwood tree — it looks like a short, ashen-faced man standing stiffly, one rotted up-thrusting branch like an arm raised to get our attention. Even dead, he explains, it provides perches where the buzzards can sleep while they wait for an updraft because the buzzards are so big they have trouble lifting their own weight with muscle. “And what the trees do for men!” he goes on. “Wood for your fire, leaves to heal you — silver cluster leaf to stop you vomiting, common spice leaves for a runny tummy, acacia thorns to pick your teeth and leadwood leaves for toothpaste, boiled knob thorn for a toothache, sour plum tree after too much wine or gin and the soft leaves…,” Brendan lowers his voice so Isabel does not hear, “…to wipe your bum.”

Brendan has only begun. He proceeds to tell of the many things he could do with the buffalo thorn: the leaf stops a wound's bleeding and a branch, the natives say, would catch the spirit of the dead if brushed across the place a person fell so you could bring the spirit home to rest in peace. Impala eat buffalo thorn leaves, and an Impala buck has to keep many she's happy. Brendan smiles. “Help a man with that, too.”

By now the notebook I thought would last me all week is already half full. I can hardly write fast enough to keep up with young Brendan's enthusiasm and knowledge. While I am still recording the last details he is onto another idea. He is telling Alfus that we should proceed from here on foot because Mr. Kennedy is a writer and they must give me good experiences to write about.

Before I can protest we are many meters from the dam, wading through thigh-high yellow grass, solemnly instructed that we are to walk in single file, that we are to stay together, that we are not to chatter, and that we are to obey the ranger's instructions without hesitation. The file is structured thus: first the tracker, next the rifle-bearing ranger, behind him the guests — Jesper is placed in front of Daniel and Isabel, he to protect them from the front, and I to cover the rear. If we happen upon something dangerous, the tracker will signal by repeatedly flapping the palms of his hands backwards at waist level toward the flank, which means we must step backward rapidly. Under no circumstances are we to turn our backs on a wild animal and absolutely never are we to run away. That is an invitation for the chase.

Before I know it, we set off on foot without the protection of the jeep, wading single file through thigh-high yellow grass

But Brendan is too far ahead at the front of the flank for me to shout out my question with dignity. Anyway, shouting is forbidden. We move forward through the grass at a brisk pace toward a tangle of small trees and bush when suddenly we stop. To my horror, I see palms flapping backwards, just glimpse a lean young lion male lying within the trees, another on his feet to the left of the clearing, eyes burning at us like Blake's Tyger. I manage to snap two pictures before the backward jog reaches me. Although I am last in the flank, I also flap my palms backwards. We are jogging quite swiftly backwards toward the dam, and the two lion are creeping toward us, one off to the left, the other to the right.

Brendan calls back over his shoulder to me, “Mr. Kennedy, just keep an eye open for any hippo in the dam! Don't get close to them!”

Oh, I think, you can be certain I will not.

In the clearing again, we huddle. The jeep is perhaps 200 meters off to our right. I am thinking how nice it would be to have my children and myself safely back in that big-animal-looking vehicle, but Brendan says, “Here's the thing. The one has cut us off and the other is flanking us. He knows we want the jeep and that's the way to get us.”

The one lion circles behind us

“I don't like that they're crawling,” Brendan says. “They're stalking us. They're hungry. They're too young to know it's best to stay away from the people.”

I'm thinking, I am not Ernest Hemingway nor was meant to be…

“I may have to fire the rifle,” says Brendan.

“Can you kill them both?” I ask.

“That would mean my job, and Alfus' job, too,” says Brendan. “I'd just hope to scare 'em off.”

We all exchange stoic glances as I regret having chosen South Africa over Greece for our vacation, and Brendan begins to make noise with his rifle, cranking the bolt and slamming it shut, smacking his palm hard against the wood of the stock. Alfus is doing a kind of dance in the grass which I very much hope is the right magic. Absurdly, I find my brain humming, Wim-o-way, Ah wim-o-way… when Brendan says, “Now they've regrouped behind us, see?”

I don't see — my eyes are shut tight.

“We have a clear path to the jeep.”

Across the spongy dam bank and soon we are piling into the beautiful, sturdy, olive-green jeep — truck really, big as a double-rhino, big enough to draw respect from a lion, two lions, even hungry ones. Brendan doesn't start the ignition. He sits there for a moment behind the wheel and Alfus turns back in his tracker's chair and begins to laugh. Brendan laughs, too, and soon we all begin to chortle, belly laugh, and that is when I realize how real the danger was.

As we pull away, Brendan points across to the tree line where a herd of bachelor impala leap off into a run — two hungry lions close behind, no doubt.

“They taste better than us,” says Brendan. “You'll see.”

For lunch there is impala pie in hot onion sauce, and after lunch we learn that Brendan has been reprimanded for putting us in harm's way. The story spreads, and no one is taken out that afternoon, we stay in the main camp. At dinner — zebra steaks in mushroom gravy — the other guests enquire with ill-concealed envy if it is true we were stalked by two lion today. Clearly they are disgruntled, feel they are not getting their money's worth. They did not get to go out on foot. They were not stalked by lion.

The leader of the camp, a short lean man with a neat brown moustache, asks if we would like a new ranger. Without having to consult, Jesper and I instantly agree we are perfectly happy with Brendan. We definitely want to continue with him. Isabel's apparent great relief is my first clue that other factors are at play here than Brendan's merely wanting to help me gather material for my writing. I am not oblivious to Isabel's beauty.

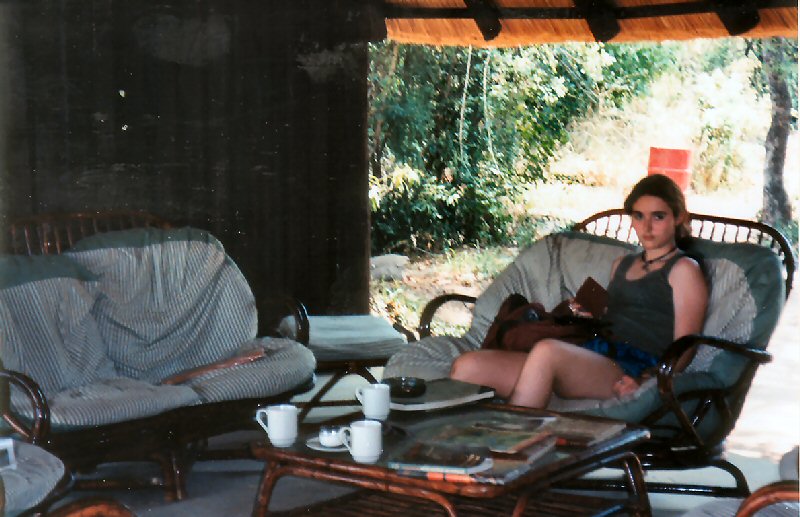

Isabel in the shade. She will become the object of our young ranger's admiration

Across the dam, a lone wildebeest, abandoned by the herd, dances madly, whipping its head in agony from the maggots planted in its brain. In the distance, we hear the bark of a dog baboon and a blacksmith plover clicking overhead, and a giggling lady flies near with a shiver of wings. Brendan shows us where a herd of elephant has passed, dragging their trunks through the dust.

When Brendan spots another tree with leopard claw marks in the bark, he parks and gives Alfus his rifle and tells him to go off to see where the leopard has gone. He wants us to see leopard. While Alfus is gone, we lounge alongside the jeep, waiting, and Brendan says, “You mustn't tell I let Alfus take the rifle. I could lose my job for that, giving the rifle to a black.”

It occurs to me that I am concerned — not because Brendan gave the rifle to a black, but because we are sitting here without a rifle to defend ourselves with. I begin to wonder about Brendan's judgment. Still, we have the jeep. Up above the crest of a hill, we see a giraffe running and an ostrich.

“There are not many ostrich any more,” says Brendan. “The lion eat them.” Then he leads us from the jeep a little way out into the field. “See here,” he says, “these are zebra tracks. Running. And see here. A leopard overtook her. The leopard are shy but they are here.”

Alfus comes back shaking his head and hands the rifle back to Brendan. I notice that Brendan is as tall as Jesper, though much thinner, and Alfus is shorter than I and has a younger face than I had thought at first. Early thirties perhaps. Brendan checks the chamber of the rifle and slings it on his shoulder.

“It's soon time for a sundowner,” he says. “Then back to the camp for dinner. Tomorrow we camp in the bush.” He drives the jeep to a water hole the size of a small pond in a clearing that slopes gently like a shallow bowl from all sides. We park. He and Alfus break out the chest with the cool drinks and snacks.

We stand around the jeep, chatting and sipping gin in the gathering dusk, sun stripes pale and low to the ground across the yellow grass and the darkening water of the drinking hole. Abruptly Brendan raises his arm for silence. “Listen,” he whispers.

At first I hear nothing, then an almost subaudible slow crunching sound. Brendan gestures with slow caution across the water hole just as the animals step out of the trees — tens, scores of them, hundreds. They keep appearing. Brendan whispers, “This herd has about 400 — I saw them on the Riebuck Plane the other day. They drink in order of rank — the bulls first. Look, you can see the last of the sunlight lighting up their eyes as they look across at us.”

Water buffalo take a sundowner

“No. They feel safe in a herd. It's only the strays that are dangerous, the dugger boys. In a herd they feel safe and would run from a sneeze back into the safety and comfort of the herd, powerful as they are. The dugger boys will charge without warning, and they don't mock charge either like most big animals. They won't tolerate anything getting too close. See that bull there, how he raises his nose to smell us. Stay close to the jeep.”

When the first wave of the bulls have drunk their fill, the next takes their place in the water, and the lead animals head slowly for the trees again. How lightly they step for an animal that weighs fifteen hundred pounds. Awed, we watch the quiet, orderly procession of enormous animals disappear back into the trees, leaving the empty landscape behind them, as though they had never been there, had been an illusion, a dream of buffalo in the dusk.

A dugger boy buffalo watches us from the trees. Wandering alone or in a group of two or three, a dugger boy is a young male separated from the herd and angry about it. Unlike other large animals, he does not engage in mock charges. Not fun to meet on a late afternoon stroll

Next day, we are in the bush where conditions are more primitive than the main camp — no roomy tents with private sinks and toilets and crisp folded sheets. Here was more like the army, though the tents were mounted on foot-high platforms to discourage crawling intruders. The shower consists of a suspended bucket with a watering can spout mounted in the bottom, and the toilet is porcelain but doesn't flush and is out in the open, behind the tents. Sitting on the bowl, you look down to the dry pit of the river bed below, dotted with fresh elephant droppings, bright brown and orange, melon-shaped balls and hyena spoor, white from the bones they eat, crushing them with their powerful jaws.

Bush tent

Bush shower

Bush toilet

We sit long after dinner, drinking gin and beer, talking by the flickering kerosene lamp, watching shadowy elephant circle by, snapping trees for night snacks, huge black shadows against the blue and green darkness of the jungle night.

Brendan tells us that the name the trackers have given him in Xitsonga is Mariband, which means one too cool to lose his temper. But that is close to another word, maraband, which means one who eats too much, so he has to listen carefully to be sure he is not being teased.

Lowering his voice so Isabel cannot hear, he says to me, “Tell me about the name Brendan, about the poet. I have heard two stories about him. One that he had many women, another that he was for boys. What is true?”

This brave young man has such concern in his eyes that I am touched. “I only know that he was a great writer and was well loved and that he had many women,” I say. Brendan smiles happily.

It is very dark, nearly ten. We have to rise early next morning. Daniel and I are sharing a tent, and I suggest we turn in.

“I'll stay up a little longer, Dad,” says Isabel. Brendan says nothing, nor does he move or look at me.

“Okay, Isabel. Ten minutes, right?”

“Fifteen.”

“I'll be sure she reaches her tent safely,Mr. Kennedy, ” says Brendan.

We light our way back to the tent by flashlight, alert to the possibility of dugger boys. Daniel retires and is soon snoring away in whatever dreams this day has inspired. I sit at the little table on the wooden platform outside the tent, shining the beam of the flashlight onto my watch from time to time. I can see the flickering kerosene lamp in the mess tent perhaps seventy-five meters away. I hear the burbling of a zebra, off in the distance the bark of a dog baboon. Brendan has trained our ears well. At ten-thirty, I step out to the path and follow my flashlight beam down to the mess tent where Brendan and Isabel sit alone on either side of the table, speaking softly.

“Better come to bed now, Bel,” I say. “It's late.” And to Brendan, “Thanks for a terrific day, Brendan.”

“My pleasure, Mr. Kennedy,” he pipes, and I follow Bel back to her tent, wishing I could be less of a stereotype.

Our last day in the bush, we drive to the Riebuck Plane. On the way we see two bull giraffe square off to fight for leadership of the herd, swinging their necks at one another's belly, gouging with skull horns. Much of the fight passes in stillness and glaring. I am unable to determine which of them, if either, is winning.

We reach the Riebuck Plane about noon and set out on foot, single file through the trees. Brendan explains that we'll follow an animal path which is a truer path, does not swerve around thorn bushes as a human path would. When we have hiked for fifteen or twenty minutes we come to the edge of a broad yellow clearing. The sun is high overhead. Sweat rolls from beneath my cap, down my back. There is nothing in the clearing other than a broad, round, chest-high bush about a third way across. The tree line on the other side is perhaps a hundred or hundred-fifty meters away. Brendan signals that we should follow him across. I'm hoping that we will see no n'goni here.

Nearly a third way across, almost at the bush, two white rhino step out of the tree line on the other side and pause perhaps seventy meters away. Brendan signals us to stop. Should we move back? “They're too fast for us,” he whispers. “And if we start moving they'll know we're here and might go for us. A rhino hits full speed in three strides and full speed is forty miles an hour. But they can't see us. They look like they can, but they can't. They're almost blind. But if the wind changes, we're in trouble. They'll smell us.” He looks at me. “If that happens, you all get down on your bellies under the edge of that bush. They'll smell you but they won't know what you are.”

This sounds dubious, but I can think of no alternative. “Daniel,” I whisper. “I'll cover Isabel. Can you manage yourself?”

“Yeah,” he whispers back.

Then we are silent. We watch the two big animals. I can feel a light breeze on my forehead. Then suddenly it riffles my hair from behind, and the two rhino heads swing toward us in one swift movement.

None of us speaks but Isabel, who says, “Shit!”

They start forward in a side by side charge. I'm poised to scoop Isabel under the bush, too frightened to feel my fear, thinking, Why doesn't Brendan shoot? But he is only making noise with the rifle, rattling the bolt, smacking the stock as Alfus dances about like a wasp on a doughnut. But the rhino are on stride three, maybe thirty meters away and moving fast as an automobile. The ground rumbles with their charge. Alfus has his cattie out and is firing stones now. The rhino are about twenty-five meters from the bush when one of Alfus' stones strike the underbelly of the bull. In unison they change direction in a ninety-degree turn and head for the trees to our right.

Brendan smiles at me. “You know that thing about hiding under the bush? I never actually tried it, but I heard it works.”

That night in camp there is much laughter. Alfus has his cattie out to show it, and he is laughing, too.

Alfus shows the “cattie” that saved the day

Jesper and I want Alfus to join us for drinks that evening, but he stays with his own while the four of us celebrate with gin and whisky and beer the continuing fact of our existence.

Next day we tip Moses and Brendan well, and we tell Brendan if there is any trouble at all about the rhino to lay the blame on us, that we insisted.

On the airplane home to Copenhagen, lifting up over the yellow landscape below, patches of green, mountain, river, blue lake and dam, I cannot help but wonder if I really experienced the days I am leaving behind there. A zoo will never again do it for me. I flip through my note pad, completely filled with my scribble and augmented by many extra sheets folded into quarters so they could fit in my back pocket. The stewardess comes with drinks. I take out a legal pad, let down my table as a writing desk. And I begin to write a short story.

The story is about a hero — the hero of our safari — Alfus*.

*The story is titled “Young Lion across the Water” and has been published in Prism International and is scheduled to appear in Atlas, An International Paperback Magazine of New Writing, Art & Image as well as in Kennedy's fourth collection of short stories, A View of the World, which is forthcoming.