|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen |

Knossos as Creative Nonfiction

Essay and Photos by Thomas E. Kennedy

At the top of Mirambellou Bay in eastern Crete, in the pit of the mountains at Porto Elounda, pleasantly sunburned, Lady Alice and I sit at the little bar, sipping a pre-prandial raki. Raki, or haraki, is the Turkish name for tsikoudia, an 80-proof grape-distilled spirit. Pale as Irish potjeen or American white lightning, it tastes like them both – an earthy, sneaky, illegal taste that I fear might leave me, if I have more than a couple, feeling as I did after emptying a quart Mason jar of home burnt with an artist named Mac Boggs in Spartanburg, South Carolina a couple of years ago, feeling empty as the Mason jar. This raki is from the private stock of Yassou, the night bartender who left it in the ice-box for me in thanks for a cigar I offered him the night before, but it is served by Antoniou, the smiling barman who comes from a village of 150 across the inlet.

“How old is this raki, Antoniou,” I ask.

Antoniou giggles. He has his vineyard across the inlet, his fruit trees, his melons, his cucumbers, his olives; he has his summer wages from tending bar, but there is almost nothing he has to buy. He has been nowhere. Once he went to visit the ruins of Knossos, 35 kilometers northwest. “Once,” he repeats emphatically. “Eet was e-nough.” And laughing goes off to serve another couple.

“Does not matter,” he says with a thick smile. “Raki ees always raki.” Antoniou has an impeccably young, full-lipped face which, when he smiles, opens like a puffer fish, though without the spikes. He is a bachelor. “I have plenty time,” he says, laughing. “How old you theenk I am?”

“Twenty-five?” I lie, and his big puffer smile flashes. “Thirty-five!”

“The bachelor life keeps you young,” I say. “No woman, no cry.” Everyone misunder-

stands that song anyway, so I might as well perpetuate the misunderstanding and use it for communication.

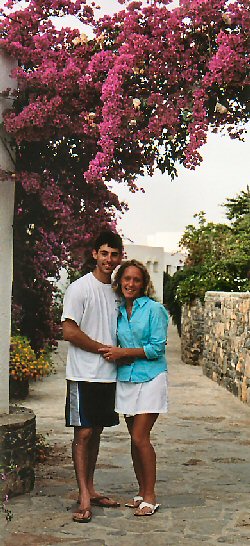

On our Cretan balcony: Lady Alice as Creative Nonfiction, Jugend style

“You see?” says Lady Alice.

I see. We are on holiday. We have both been writing all year, working ten to fourteen hour days to finish our books, which have just been published. We are here to relax. No literary traveler articles this time. No cultural journeys to Gortyn or Knossos. We will sit in the sun in our chaise lounges, sleep in our well-tended cliff bungalow in the enormous expanse of our luxury bed, raid the minibar for 7-star metaxa and diet coke, use the remote to adjust the air-conditioning to suit the late spring climate. We will swim in this incredible bay where you cannot sink – the water is like the palm of a kindly-disposed Poseidonio beneath you, holding you afloat. Lady Alice cuts flowers for the mantle over our cold stone fireplace and picks the wild spices that grow around the grounds, smudging them between thumb and finger then putting her fingers to my nostrils to demonstrate the tangy fragrance. We share fat purple plums on the terrace, enjoy the royal-sized tub. We read a bit.

Every other day I trek up to the main building of the resort here and do an hour in the fitness room before breakfast, then try to resist the eggs any style with fried mushrooms and tomatoes, Swiss potatoes, Greek sausage and succulently greasy bacon in the breakfast room that looks out over the cliff to the bay.

Lady Alice reading in the sunlight on the jetty beneath our window

I am reading René Steinke's Holy Skirts, Thomas McCarthy's Flannery's World, James Slama's Wedding Ale, and Henry Miller's Colossus of Maroussi; she is reading Elisabeth Lynneborg's Daughters of War, Frederic Dessau's Little Book on Love, and Lotte Tarp's autobiography about having been born of a Danish mother and Nazi father in German-occupied Denmark. Lotte Tarp was a beautiful Danish actress I remember from the '70s and '80s, and her book was a gift from her widower, the jazz composer Niels Jørgen Steen, whom we met in a little bar called The Fiver in eastern Copenhagen. Inside the cover, he wrote this inscription to me: “Get rid of your Irish heritage and be you! Love, NJ” So these days, I am trying to act more like my French mother than my Irish father, but it is difficult; my mother didn't drink vodka. Perhaps I should switch from Boru to Grey Goose.

And I do not write. Writing has become an illness. When the creative withdrawal pains are too hard, we translate a bit. I work turning Alice's book about the bombing of the French school in Copenhagen from Danish into English, and she works turning my literary traveler essay on the Baroness Varvara into Danish.

There are also “The Animators” to amuse us, two young Italian girls and a Dutch woman employed by the hotel to keep the guests from boredom with offers of volley ball, aqua-robics and Hollywood quizzes. There are games of chance, too – guessing the number of olive leaves in a cocktail glass or playing the human slot machine. The latter consists of their suddenly appearing like a triplet version of the ghost twins in The Shining, speaking in unison: “Hel-lo! You want to play the slot machine with us?” One of them extends an arm which you are meant to tug like that of a one-armed bandit whereupon they begin to burble until you say stop and they reveal the three cards concealed behind their backs. If they come up three the same, you've won an ouzo. Alice and I have each won once already so cannot resist the silly game or their indefatigable infectious young happiness.

It is a good life. A break. We need it.

Now, at the bar, I look out over the little inlet – mirabellou, I think, must mean beautiful sea, not snot-green or even wine-dark, but topaz-blue, turquoise-green, aquamarine, pure and clear, filled with sleek fishes who peck at the hairs on your legs and whose dark shadows fleet across the white sand floor. Small waves roll in and lap at the beige sand beach. The mountains surround us in a tall, rising-falling line against the darkening blue sky, and two sailboats bob on the water, anchored a hundred meters out.

“This is paradise,” I say.

“It's paradise,” Alice says.

“It is paradise,” says an American voice from behind us at the bar, a young woman. Her name is Denise. Her eyes are blue as Alice's, which are blue enough to light your way, and her hair is a mass of golden ringlets.

“We decided to come to paradise for our honeymoon,” Denise says, and her new young husband, Rob, steps up to introduce himself with hand-shakes, a tall, handsome guy of 29, like Denise. They have just flown in on a nineteen-hour series of connecting flights. They're half our age and if I were half a foot taller, half a hundred pounds slimmer and better looking, they might have been us half a lifetime ago.

who says Tallinn or Tashkent or Knossos.”

Denise and Rob, honeymooning young Philadelphians, underneath the bougainvillea

After a dinner of mushroom soup, dolmades, tsatsiki, pikilia, dukatas, lamb, swordfish, al dente pasta, three kinds of cheese (goat, cow and sheep), and two kinds of layer cake (bitter and white chocolate), we take coffee in the piano bar. Denise and Rob reappear to a background of music simulated by a Wizard-of-Oz machine pumped and pedaled by a young standard-singing Greek. We learn they are from Philadelphia. Rob is an independent realtor, and I think, Jesus, why didn't I think of doing that! Not only is he a pleasant good-looking fellow, but he'll be rich if he isn't already. Denise works for a publishing house but will soon switch to teaching high school geography.

“American kids don't know the world,” she says. “I'd like to do my part to make sure they don't just look stupidly at someone

They knew each other for eleven years, and then married. They had 180 guests at the banquet and cream-pied one another's faces with the wedding cake, which is apparently what people do now. Tomorrow, they tell us, they are going to Knossos to visit the Minoan ruins.

Knossos! Minoan ruins! I glance at Lady Alice. We have been avoiding this topic. Can we really come to Crete without visiting at least Knossos? Gortyn? Without a snapshot of the bust of El Greco? Or seeking traces of Odysseus Elytis (born in Iraklion in 1910, Nobel laureate in 1970) or George Seferis (1900-71, Nobel laureate in 1963)? Or following the footsteps of Henry Miller in his Colossus of Maroussi or visiting the grave of the Zorba-creator, Nikolas Kazantakis: “I hope for nothing, I fear nothing, I am a free man.” So what if the Zorba dance Anthony Quinn does in the film was composed by Theodorakis on a Turkish background and choreographed by Hollywood; most Cretans don't know that either.

Or, anyway, at least a visit to Knossos?

We sit on the balcony with Denise and Rob until the wee wee hours over metaxa and negronis and, finally, big schooners of locally-brewed Heineken, and I trot out my archive of stories which they are sufficiently well-bred to receive with enthusiasm. It is easy enough when you have thirty years on someone to give them a more or less exciting tour of their own long-gone times that they were too young to register back then. I tell about my days on Route 66 and in Alphabet City, in Big Sur and Haight-Ashbury during the Summer of Love, which was already over before it had a name. Then, because she is too modest to tell it herself, I tell Alice's story about the bombing of the French School in Copenhagen, where she was buried in the rubble for many hours at the age of five and had to dig herself out, about which she has just completed the grueling task of writing a book.

We are in bed by three, and just before I sleep I regret that instead I had not gotten more of the stories of Denise and Rob.

with friendship and good stories, adding, “The friendship and love you have for each other is something we aspire to…”

Petrified puffer fish in Elounda harbor

Next day we spend in Elounda looking at puffer fish and sea bream and clawless lobster and come back too late for dinner so we miss Denise and Rob before they sail on to Santorini and Mikonos. But there is a note under our door when we wake next morning, thanking us for helping start their honeymoon

I thought of this young couple going to visit Knossos, and I thought about how I would look when we got home and were asked if we had seen Knossos. I would look like one of the American kids Denise wanted to save from looking stupid when such places were mentioned.

II.

In the mountains above Elounda, outside a locked-up building whose roof sign identifies it as Kaklis Nightclub Live Music, the bus to Iraklion and Knossos breaks down half an hour into our journey. Alice begins to chew the red pigment from her fingernails – no doubt instead of chewing me, which I do appreciate. After another half hour without news from our young driver, a Danish woman in a red-striped blouse hugs herself and bends forward in her seat, saying, “I have a stomach ache.” Which in Danish is the nice way of saying, “I have to shit. Now.” There is a WC on the dead bus outside the closed live-music nightclub, but it is filled with spare parts and boxes where the toilet might have been. Alice offers words of comfort to the woman in the red-striped blouse.

I cannot help but feel this is all my fault. If I hadn't succumbed to the urge for another literary traveler piece, this would not have happened. We could have been sipping ouzo on the breezy beach. I pass the time with my nose in Miller's Colossus of Maroussi – with ironic appropriateness the part where in the museum at Iraklion he gets “the jitterbugs and does caca in his pants” and is told to eat nothing but soupy rice and lemon for it which is nowhere to be had so he winds up eating cold fish and olives and goat cheese and has to dash into the bottom of a dry moat and defecate alongside a dead horse beset with poisonous green flies. I pray to the Greek gods of bowels, dead horses and green flies not to cause this to happen to me or anyone I love and, if possible, to also spare the Danish woman in the red-striped blouse who is still holding her stomach.

Sigà-sigà, they say in Greece. Slowly, slowly. And slowly, slowly, a new bus appears and slowly, slowly collects the fifty other tourists on their way to Knossos. We have many stops to make, but we are on our way. Down through Agios Nikolaos, up again through the winding mountain roads to the north coast, through the dreary rows of beach towns where Germans, Scandinavians, Brits, Irish, Dutch package tourists get drunk on cheap booze and gobble questionable hamburgers and reconstituted French fries from fast-food spin-offs – Mr Sandwich, Blue Dolphin Fish & Chips, Dedalus Supermarket, Dedalos Hotel, Happiness Hotel, Maria Mini Market, Electra Apartments, the Galaxy Bar (est. 1975, sponsored by Guinness), entertaining themselves in Borsallino Video Games, and the Peach Pit Fast Food. Everything here seems ironic somehow: Amadeus Tobacco, Christi Jewels, Afroditti Coiffure, Photo Phantastico, Cash & Carry (carry what?), Byron Rent-a-Car…

It occurs to me that the good Lord, George Gordon, might have left a child here, Giorgios Byron, perhaps, whose descendants rent out cars. Childe Harold did drive his chariot to the stars…

Our bus collects its last group of tourists from the last hotel, and we are joined by our tour guide, a tall young dark-haired Dane with large smiling teeth. His name is Brian (Bree-an), and he lectures us through a hand-held mic on Greek mythology:

“Just as we Christians have our myth about the creation of the world, so too did the Greeks…”

With gleeful expectation, I crane my neck to study my fellow passengers, hoping to see an apoplectic Republican creationist, but only Nordic faces gaze mildly back at me. To them, everything is a myth – except for the revenue service which every month collects 0.5% of their income at the source and pays it to the state church.

Bree-an seems to know his subject. He tells us about Gaia, the earth mother who arose from Chaos along with Tartarus (the underworld) and Eros (love), how Gaia gave birth to the starry heavens (Uranus) and the sea (Oceanus), how twelve Titans were born of Gaia and Uranus.

To Lady Alice I offer a feeble joke: “Must be the first anal birth.” Only Lady Alice can convey, with such a mild glance, a message of such scathing contempt.

Two of the Titans, Bree-an continues, were Chronos and Rea. Chronos, the original father, feared being dethroned so he ate all his children (Hestia, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, and Hades) – all except for one, Zeus. Zeus induced vomiting in Chronos, then cast him into the underworld and divided up the kingdom with his brothers: the sea to Poseidon, the underworld to Hades. For himself, Zeus claimed power and took up residence on Mount Olympus.

“With over 30,000 gods, goddesses, demi-gods and supernatural creatures,” Bree-an informs us, “it is impossible in the short time we have to give an overview of the gods and their various relationships.” But he names some of the more prominent among them: Athena (wisdom and the art of war), Hera (the wife of Zeus and protectress of marriage), Aphrodite (love, fertility and beauty), Demeter (agriculture), Dionysus (wine), Ares (war), Apollo (light, clarity and song), Artemis (sister of Apollo, goddess of the hunt), Persephone (Demeter's daughter and queen of the dead), Hermes (messenger of the gods, protector of travelers, businessmen and thieves)…

It occurs to me I once knew all this, in Greek and Latin both, thanks to the tireless efforts of Brother Anselm at Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School in the '50s, but must admit I have forgotten most of it. It occurs to me I have forgotten so much of what I knew. How can a person forget so much? I can so clearly remember Brother Anselm, a small dark quiet man who wore large dark-framed spectacles that left red marks on the bridge of his nose when he removed them to rub his eyes, and who habitually moved his lips as though his teeth might have been bothering him. I can remember the mimeographed sheets he printed for us, purple ink on mimeo paper, forty-five years before. I can remember the inky smell of those sheets, but I cannot remember more than a few of the words on them.

Out in the middle of a plateau that rolls past is an enormous sign that says, INTERAMERICAN, and Bree-an is now telling us that the first art appeared on Crete some 8,000 years ago, clay urns and statues. Five thousand years ago came the Bronze Age and the Minoan civilization arose, lasting a thousand years with its half-timbered palaces. The Minoans are said to have been a peaceful, mercantile people (even if they did feed Athenian youngsters to the Minotaur!), light-haired and blue-eyed, about 5' 4” (165 cm) in stature. Men and women enjoyed equal status, although the women were considered closer to the gods. The Minoans also believed in a life after death. Here began the Linear A alphabet about six thousand years ago, followed by the so-called Linear B.

The Minoan culture was at its high point about 1450 BC, but its great palace at Knossos was destroyed by an earthquake. The palace was rebuilt, but a second earthquake struck around 1400 BC, and this time, they could not manage to rebuild. Then the Myceneans, a warrior people, came and took over.

Bree-an relates the myth of King Minos and the Minotaur and the labyrinth of Knossos. Minos was of divine origin, sired by the king of the gods, Zeus, with Europa, at Gortyn. Poseidon had sent Minos a white bull which the god wished Minos to sacrifice to him, but Minos wanted the white bull for himself and substituted another as an offering. Offended, Poseidon caused Minos' wife to fall in love with the white bull, and Daidolos – ever helpful artificer in residence – built a model of a cow in which the queen could conceal herself and couple with the white bull. From this union was born the Minotaur, a monster with human body and bull's head.

In another context, Minos forced an Athenian king to send seven boys and seven girls periodically to be fed to the Minotaur in the Labyrinth, also designed by Daidolos to contain the monster. In Athens, Theseus volunteered to join the third group of victims sent to the monster, in order to have an opportunity to kill it. In Knossos, Theseus won the love of Ariadne, daughter of Minos. Ariadne appealed to the helpful Daidolos to assist her in saving her lover. Daidolos showed her the way in and out of the Labyrinth, and Ariadne gave Theseus a “clew of thread,” tying one end to the entrance. Theseus killed the Minotaur and found his way out. On the return voyage from Crete, Theseus and the other young men and girls went ashore at Delos and danced the sacred crane dance (which sounds rather piquant). But afterwards, he abandoned Ariadne on the beach (ungrateful bastard!) where she was discovered by Dionysus, who fell in love with and married her.

Minos was now enraged with Daidolos, who fashioned wings for himself and his son Icarus on which to fly away, but the wings were made of wax, and despite his father's warnings, Icarus flew too near the sun, his wings melted, and he drowned in the sea that is named for him (the Ikarion Sea).

Minos pursued Daidalos to Italy where he was killed and buried in a great tomb there at Minoa in Sicily, as reported by Herodotus.

At this point in the historical-myth of the Cretan world according to Bree-an, our bus has reached the archeological museum in Iraklion, and Bree-an leads us into a sweaty, shadowy archway where people swarm and queue to buy tickets and get into the museum. Four hours has been allotted to the museum tour, but clearly half of that time will be passed waiting in this sweaty archway, so we ditch the tour and go to drink retzina on the Four Lions Square in the Four Lions Café. At the center of the square a burbling round fountain is adorned with four stone lions at each of its compass points. In the café, from behind my sunglasses, I watch the passing Callipygian wonders while Alice watches the waiters stationed at each of the café's four corners, ordering passersby to patronize their restaurant:

“Come een! Sit! Eat! Eat here! Why not!?”

“Those four waiters are the real four lions,” says Lady Alice. “Hungry vons.”

Restaurant Four Lions on Four Lions Square in Iraklion, where one may eat many small fish washed down with cold retzina for a pittance

On either side of the café is a police station and a tattoo parlor, and just across from us a red rounded 'M' on a signpost beneath which is printed, in English, “I'm lovin' it” and an arrow on whose bar it says, “300 meters.” What would excavators a thousand years from now make of that rounded 'M'? I wonder.

'M', symbol of the late American Empire deity of commerce, grease, and mass manipulation. The 'M' became not only a unit of global economic comparison, but also a means of control and manipulation of the masses whose stomach acids were programmed to be triggered at the sight of it, creating the need to ingest the sacred slab of beef and deposit an offering to the benevolent god of M. The 'M' communion food was also used to deplete the strength and vitality of the potentially rebellious youth of the lower classes and racial minorities in that declining period of the American empire.

I was hatin' it. Who would eat a McAnything when for a pittance you could have a platter of small grilled fishes, a salad of tomato, cucumber, olives and goat cheese – all fresh – and a liter of resin wine? That's what I was lovin'.

While we gobbled our little fishes and quaffed our retzina, I boned up on the Knossos literature I had purchased, several slender books with copious illustrations, and Lady Alice chatted in French with two elderly postcard-writing lady tourists from Provence at the next table – elderlier than us, that is, I think; gazing out through the fortress chinks of one's own eyes, one loses sight of how elderly one might oneself be perceived to be. I tend to think of myself as a lad until I catch a glimpse of my agéd hands.

“Ah, Provence!” I say to the elderly French ladies to assert my presence.

“Non!” says the one. “Provence!”

“Right, Provence.”

“Non, monsieur! Provence! Provence!”

Soon we are on the tour bus again for the brief transport from the museum to the palace in the company of all those who had had the benefit of the Iraklion museum briefing.

“Was it worth the visit?” I ask a very old, super sized Swede whose bald, bullet-shaped skull makes me think of Tor Johnson, the Swedish Angel. He is smoking a king sized Mayfair and reflects before replying.

“I could not get an answer to my question,” he says and puffs. “I vant to know if it is pos-sible that Knossos was destroyed by ancient tsunami.”

His wife, a little blond-grey slip of a thing, smiles at me. “It is funny,” she says, “with all of those symbols they had in olden time.”

As the large Swede mentions the tsunami, I notice the sky darkening. It is funny with all those symbols, I think.

Near the entrance to the ruins, on a tall pedestal, rises a bust of Sir Arthur Evans, author of all this. It must please him that we all, even the two-meter tall Swede, must

“That script,” Bree-an informs us, “was the so-called linear A script. It has never been deciphered and so the Minoans original language is still a mystery for us. The Linear B script was spoken when the Palace was destroyed the last time in 1450, a Mycenean language. It was deciphered in 1952 by another English, named Ventris, which proves that around 1450 a Mycenean dynasty ruled at Knossos, speaking the oldest known form of Greek, also used on the mainland at that time.”

look up at him, for in life he was a mere 5´1” (157 cm). Behind and above him, the trees and sky are strangely dark, and I hear the distant murmur of summer thunder. Diminutive of stature, short of sight, long of imagination, and strong of will, Sir Arthur purchased the area around Knossos in 1893, inspired by the archeological findings of Heinrich Schliemann and convinced by his own studies that a pre-Homeric script dated back to Crete and what he would call the Minoan culture on the background of the myth of King Minos. I wonder if the king's wife really copulated with a white bull and gave birth to a monster.

Sir Arthur Evans, prime mover of the Knossos excavations and reconstruction, was present in 1935 at the unveiling of this bronze bust. He died in 1941 at the age of ninety after forty years of research into the Minoan civilization, which includes his four-volume study, The Palace of Minos (1921-35). Although there has been considerable controversy about his archeological reconstructions of Knossos, his work was scientifically recognized when he was awarded a professorship at Oxford in 1911.

The large Swede, puffing a freshly-lit Mayfair, asks, “Was this also the language they speak at time of the palace destructions by tsunami?”

Bree-an blinks at him and smiles with his many teeth. “Who knows?”

Stub of admission ticket from Knossos

|

And we file in through the gate, presenting our tickets on which are reproduced the image of the alabaster throne considered the oldest throne in Europe, found in situ here, and on which Henry Miller claimed to have sat. More recent speculation, however, suggests it was the throne of a queen because it is too narrow to accommodate the backside of a king. Curious. Possibly it was intended for a high priestess of the mother goddess cult. |

Ancient reproduction of the original throne, an exact copy carved in wood and placed just outside the knossos throne room |

The Cretan snake goddess of Knossos (circa 1600 BC) |

Bree-an proceeds to spout from his fount of knowledge. Unlike modern palaces, the Mycenean palaces served many purposes – as a seat of administration and justice, a commercial and manufacturing center, as a store house for goods, for the levying of taxes on goods, for art workshops, and they also played a religious role. The west wing of Knossos was dedicated to the cult of the mother goddess to which was connected the bronze statuette found here of a bare-breasted goddess handling two snakes. |

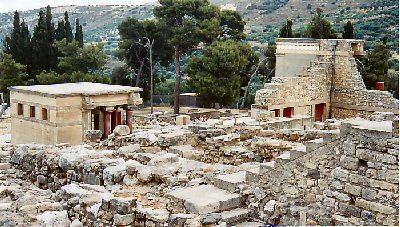

I had expected something more like a building, but what lies scattered and stretched out before us here is a series of ruins, broken walls, reconstructed pillars. The original pillars were said to have been of wood, but Sir Arthur's attempt to reconstruct them failed so he had concrete pillars poured and had them painted red to distinguish them from the original structure. Some of the beams are also concrete, but painted, I notice, to resemble wood grain.

Concrete supporting beams painted with wood grain simulation

The restored west bastion of the north entrance passage, equipped with a copy of the relief fresco of the charging bull in an olive grove

Artificial, painted reconstructions amidst genuine rubble of Knossos.

What is real here?

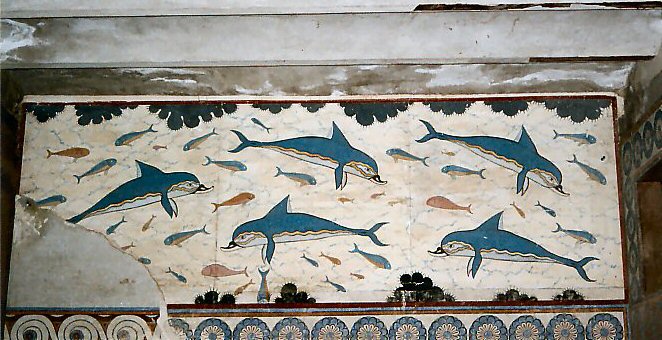

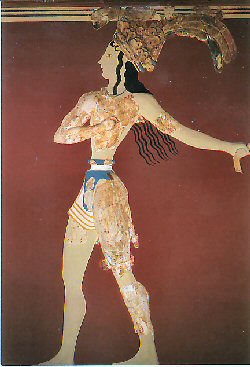

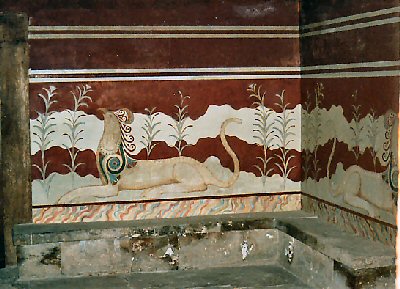

The ruins are crawling with tourists, mostly large groups like our own, being shepherded by a guide. The air is filled with the mutter of tour leaders lecturing in many languages. As we thread through the west portal, the procession corridor leading from the west court to the South Propylaeum, we pause to admire the Fresco of the Procession – young Minoans carrying ritual vessels which one of my guidebooks, hurriedly thumbed through, informs me dates to the fifteenth century BC. From another of my books, I learn that these are replicas, reconstructed replicas. I begin to get another thought about the wonder I felt seeing reproductions of the beautiful frescoes here and there throughout the ruins: “The Ladies in Blue” from the east wing, the Dolphin Fresco from the queen's Megaron, the reclining griffins flanking the throne in the throne room, the co-called “Prince of the Lilies” next to the south entrance. I've been seeing reproductions of these images everywhere, even on the little paper bags from the hotel newsstand, and am puzzled by the modernity of their appearance.

The Ladies in Blue fresco from Knossos' east wing

Dolphin fresco from the Queen's megaron. Sweet as a Disney fish

The dolphins make me think of Disney and the ladies in blue and prince of lilies look strangely like art deco figures. Following the procession of tourists and tuning out the knowledgeable yammering of Bree-an, I find a note in my Davras guidebook about “The Prince of Lilies”:

According to a recent study, this rich yet simply clad figure with bare torso and crown or diadem with standing lilies surmounted by three large backward trailing peacock plumes constitutes, unfortunately, an erroneous reconstitution of fresco fragments belonging to three different figures, two boxers and a priestess, who wore the lily crown.

The Prince of the Lilies fresco, concocted by a Swiss Jugend painter out of fragments from three diffeent frescoes and the glue of imagination

I dig into my shoulder bag for another of the guidebooks – this one in Danish by Annette Dockweiler:

The restoration of the frescoes was delegated by (Evans) to Swiss father and son artists named Gilliéron, who employed picture fragments to reconstruct large colorful works of art, guided more by the desire to see a complete work of art than by scientific exactitude. Thus the frescoes stand forth today as a peculiar mixture of the Minoan original, historicist (blending of many styles and forms) and the then contemporary and prominent Jugend style.

Reclining gryphon fresco in the throne room

The thunder rumbles closer overhead. I feel a drop of rain simultaneous with an epiphany: Sir Arthur Evans practised creative nonfiction! These reconstructed ruins are an artifact built of tiny fragments of reality, hunks of Homeric myth, an assortment of historical forms and elements of art and architecture, and a scatter of original stones and facts. This ancient place is some kind of cross between an historic ruin and a Disneyland interpretation of a mythic history boiled together by a Henry Miller like hyperbolic enthusiasm.

I feel as though I am dangling somewhere between history and a comic book, animated into a Tintin or Donald Duck adventure. It is one thing to contemplate a myth or the fragment of an ancient urn, yet another to experience an archeological site as Disneyland, the archeologist auteur as a carnie barker, five foot one in spats with megaphone and cane baton, wearing a British title: “Hur-ree hur-ree hur-ree! See the Lilly Prince and the dancing ladies in balue, see the cult of the bare-breasted snake goddess in her su-linky gypsum throne!” I cannot help but wonder how Denise and Rob might have experienced it here yesterday, what Denise will tell her high school geography students about this place.

Raindrops are falling more frequently now, and the thunder seems to roll closer from far off across the vast, low ceiling of sky.

III.

Later, back at the hotel restaurant, brushing raindrops from my shoulders, I ask the waiter with the bushy mustache what weather to expect tomorrow. He usually knows. He thinks for a moment, then without smiling, he says firmly, “Snow.”

In the middle of the night an enormous explosion wakes me. I sit up in bed. Lady Alice is staring at me, her blue eyes wide in the dark. I check my watch. 3:30 a.m. The room illuminates with eerie silver light that reflects in her eyes, and but a second later, another explosion of thunder cracks against the wall of our balcony outside. An ultra short flash-to-bang time. The lightning is very close. Again it flashes, explodes – too quickly for me to measure the lapse by counting.

My job now is to reassure Lady Alice who grows restive at the sound of thunder. I usually find it exhilarating, but I've never heard or seen anything like this before. I go to the window and look out to the little harbor. The rain is torrential, flinging itself downward. The two boats anchored there are bent flat against the water. Currents of lightning crease the sky like silver-white laser blades, and the thunder is so close I can feel it in the floor, in the soles of my feet. Branches and lounge chairs are flung about the beach and the walkways below. The towels we hung out to dry on our balcony are gone, the balcony itself several inches deep in water. I think of the big Swede and his tsunami fixation. But there have been so many catastrophic storms lately. I remember the waiter's prediction of snow. A joke, right?

This will end any moment now, I think and pour myself a triple vod, a steep Fernet Branca for Lady Alice. We drink in the dark, smoking, startled by every flash and explosion, and after a half hour it still has not ended, after an hour it is still going strong. Lady Alice packs a shoulder bag with her credit cards, cash, medicine, passport, one of the books she has been reading, make-up, clean underwear. She zips it shut and places it on the floor alongside her chair.

I want to smile and kiss her forehead, but I'm too busy considering gathering my own valuables. I begin to contemplate what I would do if I looked out the window and saw a ten meter wave sweeping across the harbor toward our bungalow. We are surrounded by mountains. Could we run uphill fast enough to escape the water? I think of the Minoans and Mycenians, what they might have thought when the ground began to tremble and crack beneath their feet, walls crumbling around them. I think about what the Thailand and other tourists and locals might have thought as they saw the tsunami rolling toward them. I wonder if this bungalow is grounded. Everytime I see Lady Alice's wide eyes illuminated in the lightning, I try to think of something to say that will help her to relax, but no words find my mouth.

Then some impulse has me rise and balance on one foot, bending forward sharply at the waist, one leg extended behind me, arms straight out like open wings, chin thrust upward, teeth bared.

Lady Alice's mouth hangs open, her blue gaze seems to waver between terror and amusement. “Vhat in the name of Satan are you doing?”

“This is the formal posture of invitation to the sacred crane dance,” I explain, almost giggling, uncertain whether I am on the edge of hysteria. “Hurry,” I say, “before my lumbago kicks in!”

“You are a crazy von,” says Lady Alice, rising to join me.

And we dance, as best we can, the sacred dance, washed over by silver flashes of light.

Sleep comes before the storm exhausts itself.

In the morning the balcony is still deep in water, but it is dripping off. The beige sand of the beach is mud-dark, strewn with refuse, but the water of the bay is still, the sun shining. Within a couple of hours we are sunning ourselves on chaise lounges out on the wide stone jetty. I've invested in a diving mask and snorkel and a fishing net. Hotel employees are out gathering up the garbage, cleaning the sand, draining the lawns. By eleven the bar is open, and my sandaled feet flap me up to order a schooner of draft and a campari-orange for Lady Alice.

The three animators are there, crazy triplets from the Overlook Hotel. “Hel-lo,” they say in unison. “You want to play weeth us?” And they begin to burble like a slot machine.

Puffer-smile Antoniou watches from behind the bar. “How you like our storm last night?” he asks.

“Loved it,” I say. “Can you do us up another for tonight?”

He giggles wildly as though I am not making any sense at all.

Davaras, Costis. The Palace of Knossos (tr Alexandra Doumas). Athens: Editions Hannibal, undated, 50 pp.

Dockweiler, Annette. Turen Gør til Kreta. Copenhagen: Politikens Rejsebøger, 2003, 132 pp.

Michailidou, Anna. Knossos: A Complete Guide to the Palace of Minos (tr Alexandra Doumas, Timothy Cullen). Athens: Ekdoltike Athenon SA, 2004, 128 pp.

Miller; Henry. The Colossus of Maroussi. New Directions, 1941. 244 pp.

Sakellarakis, J. A. Herakleion Museum, Illustrated Guide (tr Sylvia Moody). Athens: Ekdotike Athenon, 2003, 144 pp.

Vasilakis, Adonis S. The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (tr Aliki & Koutsaki-Vasilaki). Heraklion: Editions Mystis, undated, 86 pp.