| an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins |

|

DISQUIET ON DOURADORES:

LITERARY LISBON

Bernardo Soares, the fictional author of Fernando Pessoa's The Book of Disquiet, both lived and worked on the fourth floor of buildings on Lisbon's Rua dos Douradores. Of that street he says,

And if the office on Rua dos Douradores represents life for me, the fourth-floor room where I live, on this same Rua dos Douradores, represents Art for me. Yes, Art, residing on the very same street as Life, but in a different place. Art, which gives me relief from life without relieving me of living, being as monotonous as life itself, only in a different place. Yes, for me the Rua dos Douradores contains, the meaning of everything and the answer to all riddles, except for the riddle of why riddles exist, which can never be answered.

(Richard Zenith translation)

Rua dos Douradores

Rua dos Douradores

|

Rua dos Douradores is a real street, just four blocks long, not far from the center of Lisbon, close to two large and impressive campos, the Praça Dom Pedro IV and the Praça do Comércio, and a short distance from the Tagus River. Also just moments away is the Elevador de Santa Justa, a 100-foot-tall lift built at the turn of the twentieth century that serves no function but rising to a restaurant with a panorama of the city and its harbor. |

|

Rua dos Douradores itself is nondescript , narrow and ordinary, too cramped to offer a good look at the buildings, a number of which have the height of four or five stories. Even though Pessoa/Soares wrote seven or so decades ago, the rua probably hasn't changed much beyond the shops at ground level and the people and businesses within. |

Elevador de Santa Justa

Elevador de Santa Justa

|

Praça do Comércio

While Pessoa subtitled The Book of Disquiet “A Factless Autobiography” filled with a collection of 481 brief musings on the meaninglessness of life, he does offer a few facts now and then—the names of Soares' co-workers and of other streets nearby. This precision of cartographical details seems typical of Lisbon writers, as if they have a need to ground their characters in specific locations because the neighborhoods are crucial to the identities of their people.

Soares was more than a pseudonym for Pessoa, but rather one of a number of what he called heteronyms, which differ from pseudonyms because they are distinct personas with extensive biographical details and with unique literary styles and subjects often nothing like Pessoa's own. They wrote and published prose and poetry in English as well as Portuguese. Pessoa began inventing them in childhood and developed many of these identities throughout his life. One of his English translators, Richard Zenith, has counted approximately 75. At the end of his version of Disquiet, Zenith gives brief histories of the 18 most significant.

Zenith regards Soares as less of a heteronym than others because his is a “mutilated” version of Pessoa's personality. One commentator finds a fundamental difference between the flesh and the fiction in that Pessoa was a sociable witty man, “fun to be with.” One is reminded of the comparison between the singing James Joyce and his somber alter ego, Stephen Dedalus.

Soares' connection to his city is paradoxical. While he reveals an estrangement from all things around him, he still cannot exist without them. In his concluding statement, number 481, he says,

Nostalgia! I even feel it for the people and things that were nothing to me, because time's fleeing is for me an anguish, and life's mystery is a torture. Faces I habitually see on my habitual streets – if I stop seeing them I become sad. And they were nothing to me, except perhaps the symbol of all life. (Richard Zenith translation)Anticipating his own death, his disappearance from Lisbon, Soares' final sentence is, “And everything I've done, everything I've felt and everything I've lived will amount merely to one less pass-by on the everyday streets of some city or other.”

In 1984, a half century after Pessoa's death in 1935, José Saramago, the 1998 Nobel Prize winner, resurrected one of the heteronyms and had him spend hours walking the streets of Lisbon. His title, in English, was The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis. Reis,a physician-poet, according to Pessoa, emigrated to Brazil and wrote classically inspired odes. Zenith characterizes these poems as advocating “a stoic acceptance of life with its small and fleeting pleasures, its inevitable sorrow, and its lack of any discoverable meaning.” Perhaps what distinguished Reis from Soares is that he kept his overt broodings to his short poems and became obsessed with two women.

For this novel, Saramago also resurrects Pessoa, in this case literally, because the story is set immediately after his death, and his spirit often appears to Reis at unlikely times to engage in discussions that border on arguments. As this Pessoa explains, the newly dead are granted nine months of earthly connection before they actually leave. In fact, Pessoa is sitting at the foot of Reis' bed, when Reis realizes that he too has died, having survived a number of months beyond his original creator.

On one of his walks about the city, Reis wanders onto the street of Soares' life:

Ricardo Reis went around the square from the southern side and turned into the Rua dos Douradores. The rain almost over, he could now close his umbrella and look up at the tall, grimy façades. Rows of windows at the same height, some with sills, others with balconies, the monotonous stone slabs extending all along the road until they merge into thin vertical strips which narrow more and more but never entirely disappear. (Giovanni Pontiero translation)

Rua do Alecrim |

Until he finds his own apartment, Reis spends most of his months in Lisbon living in the Hotel Bragança at the beginning of the Rua do Alecrim, taken there by a taxi driver immediately after he disembarks from the ship that brought him home after 16 years in Brazil. |

| No doubt the Rua do Alecrim was a conscious choice by Saramago because that street leads to what might be called the literary center of Lisbon as it climbs to Rua Garrett. Not only does it offer a number of book stores, there and on its renamed continuation, the Rua da Miseracordia, it passes the statue of the nineteenth century novelist Eça de Queiroz, who is dressed as a gentleman but inspired by an open-armed naked muse. |

Eça de Queiroz |

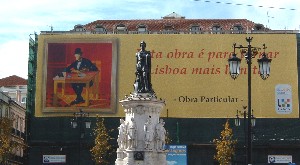

Pessoa and Camões

All this is on Rua Garrett, the main shopping street of the Chiado district of the city. The street is named for author and poet João Almeida Garrett (1799-1854) and the district with the nickname of the sixteenth-century poet António Ribeiro, who has his own statue not far from the seated Pessoa.

Pessoa lifesized

But a life-sized bronze three-dimensional Pessoa is seated across from the park on a chair among the pavement tables of the Café Brasileira, an empty chair beside him for who knows what companion and the posing of tourist photos. A bookstore occupies the shop next to the café, which has been a longstanding gathering spot for writers and intellectuals.

Eça de Queiroz located his 1878 satirical novel, Cousin Bazilio, firmly in Lisbon also, specifying streets, places, and neighborhoods. In fact, one character, Julião Zuzarte, an impoverished surgeon with no clientele, “was beginning to grow weary of his fourth-floor room in the city's low-lying district, Baixa, of cheap suppers and of his old-fashioned, threadbare overcoat.” Another dreary fourth-story life.

Though we all know national stereotypes are problematic, our Eyewitness travel guide to Portugal notes that “there is a deep-seated aspect of the national psyche which the Portuguese themselves call saudade, a sort of ethereal, aching melancholy which seems to yearn for something lost or unattainable.”

That characterization led my wife and me, as we wandered the same streets as Pessoa, Saramago, Soares, Reis, de Queiroz, and Zuzarte, to sample an evening of saudade embodied in the Portuguese folk music called fado, choosing Café Luso and following an eager host into a nightclub packed with American tour groups.

But once the tourists filed out, happily, and the audience shrank, a curtain closed the room down to about a third of its full size and the musicians relocated themselves for a more intimate performance, their voices strong, their fingers adept.

Between performances of the male and female singers and the guitarra solos, costumed dancers brought out banners that they handed to the Americans and led them in a parade across the stage while the house photographer snapped souvenir photos.

Café Luso

Although we don't understand the language, it was easy to tell that this was an emotional music of lament and longing. “Fado” translates as “fate,”, clearly not a happy one. One discussion of the music says that the success of a performance is judged by the tears of the audience.

Could it be that the Lisbon earthquake of November 1, 1755 still marks the city and its temperament? It was an All Saints' Day, and almost two dozen churches collapsed, crushing the worshippers. Fires erupted, the Tagus River flooded whole areas of the city. Approximately 15,000 were killed and half the city ruined. Not only was the earthquake a devastating event in Portugal, it shook the Enlightenment faith of all Europe. How could such a disaster have occurred in the best of all possible worlds? Was it divine wrath? Was nature less than hospitable to human kind?

Alexander Pope had stated a Leibnitz-like world view in “An Essay on Man” (1733-34): “One truth is clear, Whatever is, is RIGHT.”

Mocking such assumptions, Voltaire wrote “Poemè sur la disastré de Lisbonne” and used the disaster in Candide as evidence to attack Leibnitz's theological optimism. In a letter to M. Tronchin 24 days after the earthquake, Voltaire expounded on his pessimism:

This is indeed a cruel piece of natural philosophy! We shall find it difficult to discover how the laws of movement operate in such fearful disasters in the best of all possible worlds — where a hundred thousand ants, our neighbours, are crushed in a second on our ant-heaps, half, dying undoubtedly in inexpressible agonies, beneath débris from which it was impossible to extricate them, families all over Europe reduced to beggary, and the fortunes of a hundred merchants —Swiss, like yourself —swallowed up in the ruins of Lisbon. What a game of chance human life is!

The Marquês de Pombal in his Metro Stop |

Central Lisbon was rebuilt under the guidance of the Marquês de Pombal, who designed a grid pattern that resulted in the city we know today. But could there have been a psychic aftershock in men like Soares and Reis, doubts about the permanence of the ground beneath them? Despite his heteronym Soares' disquiet in Lisbon, Pessoa appears to have had a great affection for the city, writing an enthusiastic guidebook called Lisboa: What the Tourist Should See |

Perhaps making Lisbon so prominent in their works—despite the saudade of their characters—reveals that the writers truly care for the city as a living entity. My wife and I found evidence for that in the afternoon spent with an award winning poet and novelist, Orlando da Costa, whose 50 Years of Literary Life were celebrated in 2001 in Portuguese cities and in his native Goa. Born in

|

Mozambique and raised in Goa, he came to Lisbon for university studies in 1947 and stayed on, writing and opposing the Salazar dictatorship, with the result that for a time his works were banned and their author imprisoned. |

Orlando da Costa |

The Cenotaph for Camões

Senhor da Costa took us to lunch in a tiny restaurant space of tiled walls and excellent sea bream, then across the street to a pastelaria for a dessert of sweet pastéis (custard-cream tartlets) and rich coffee. The food, the sights, and the company were more than enough to counteract any inclinations of disquiet we may have felt. But we didn't return to the Rua dos Douradores. Once was enough.

[copyright 2003, Walter Cummins]