| an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins |

|

N'Yawk N'Yawk:

Digs & Haunts of Writers

New York August heat is enough to drive a man mad. Woman, too. Airconditioners churn at full force, dripping on your head as you pass beneath them, but they have yet to concoct an airconditioner that can cool the streets. Out here you work up a constant thirst with plenty of cool places to quench it. I have idle hours and wade the naked steaming streets in shorts, armless teeshirt plastered to my sweaty back, paying attention as best I can. To give my visit form, I seek out places where writers have lived or drunk, as good a structure as any, though an impossibly ambitious one. It would no doubt be easier to draft a list of the writers, artists and musicians who didn't live here at some time or another than the ones who did.

How many, for example, are aware that Antoine de Saint Exupéry (1900-44) wrote The Little Prince here, on the 23rd floor of 240 Central Park South at Columbus Circle where he lived during the German occupation of France in World War II? He died on a military reconnaisance flight over France in July 1944. It exasperates me that I have only just learned that he lived there, just across from where I worked for several years in the 1960s, on the 12th floor of the now demolished Coliseum Office Building at 10 Columbus Circle, at the time I first read The Little Prince. And what, you may ask, would it have mattered if I had known? Perhaps nothing. Perhaps a good deal. Is it of value to cultivate our awareness of great things that have been accomplished just across the street from where we toil in drudgery? I think it does. I want to know these things. I want to know the geography of it, the housing.

Columbus Circle, New York Coliseum coming down. Across the street from here in 1944, on the 23rd floor of 240 Central Park South, Antoine de Saint Exupéry wrote Le Petit Prince

In order to make my search for such knowledge nominally superable, I focus mostly on the Village, but even that is too much. Should you want to plot the poetic production of Alan Ginsberg against his residences, for example, you will find that in the East Village alone he lived in half a dozen apartments between 1952 and 1997. For those fellow-obsessives who might want the list, here it is:

206 East 7th Street (1952-53)

170 East 2nd Street (1958-61)

704 East 5th Street (1964-65)

408 East 10th Street (1965-75)

437 East 12th Street (1975-96)

404 East 14th Street (1996-97).

Ginsberg, too, unbeknownst to me, lived just around the corner from where I lived in 1966, at 184 East 3rd Street, between Avenues A and B.

The Croton, 170 E. 2ndSt between A & B, one of Alan Ginsberg's many NYC residences

Hell's Angels NYC Headquarters on East 3rd Street

|

I wade through 95 degree humidity and 92 degree heat to revisit my old digs and to acquaint myself with his. On the way, I pass the Hell's Angels NYC Headquarters which has been considerably spruced up since they were my neighbors 3½ decades ago. Their building is decorated with a flag-bearing patriotic poster: Support the troops…Love It or Leave It – which perhaps suggests something about the mind-set of our current leaders' policies and of the authors of the the Act entitled “Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001” mostly known by its |

|

Understandably my own ex-digs at 184 East 3rd Street between Avenues A and B retain no mark of my six-month stay there in 1966-67, during which I wasted my time inhaling, although in my cups one night I commissioned a psychedelic grafitti artist to adorn the walls of my first floor studio with magic marker murals. The apartment became a curiosity amongst the neighbors; strangers would knock on my door to come in and view the array of naked dayglo popes, uncomplimentary effigies of Lyndon B. Johnson and Jedgar Hoover and assorted other caricatures, cartoons and obscenties. My departure in February 1967 was at midnight with forfeiture of my $100 deposit. |

184 East 3rd Street between Avenues A & B where the author lived and inhaled in 1966 in a $100 a month studio apartment that now rents for ten times that

|

The redneck bar across the street, with its nasty little yapping dog named Susie, is gone as is, south across Avenue B, the once great Slug's at 242 East 3rd Street (between Avenues B and C), just around the corner from where Charlie Parker lived from 1950 to 1954 at 151 Avenue B. Slug's hosted new jazz (Ornette Coleman, Pharoah Saden, Albert Ayler, The Sun Ra Arkestra) from 1965 to 1972 when it was closed after trumpetist Lee Morgan was shot to death there.

I said my own final goodbye to the area in 1971 after my girlfriend's neighbor fired a rifle through her apartment door because her dripping faucet was driving him nuts. He had warned her the day before he would kill her if she didn't fix it. By luck, although she was standing behind the door, she was not hit, but the sight of the bulletholes was enough to make me lose interest in the area. She and I moved to Queens the next day.

When I had moved to the East Village it seemed a place where classes and races mingled in peace – Salt 'n Pepper City one of my friends called it – but in 1967 a hippie named Groovy and his coffee heiress girlfriend had their skulls smashed with cinder blocks by two black dudes in connection with an amphetamine transaction; the headline in the East Village Other said it all: Groovy is Dead. I recall ominous incidents in Thompkins Square Park – inter alia a very strange guy who used to shuffle around mouthing a mantric chant of Ever see a naked white woman? Hangin' by her hair? All covered with blud?

Murder statistics for the city as a whole climbed steadily from 1963 to a peak in 1990 of 2,245. The figure for 2002, at 587, was the lowest since '63. A recent article in the New York Times reported, as if consolingly, “…on average fewer than two people are murdered in New York City each day.” Nice for everyone except the chosen two.

236 East 3rd Street between B & C. Nuyorican Café, home of Puerto Rican and other poetry

|

Since 1972, East 3rd between B and C has beeen the home of the Nuyorican Poets Café at 236, founded to give voice to Puerto Rican poetry but also to poets like |

Kenkeloba Sculpture Garden on East 3rd St between B & C

|

Further down 3rd is the Kenhelbaba Sculpture Garden which advertises an entrance on East 2nd, though I am unable to find it. What I did find on 2nd was Ginsberg's |

I have plans for lunch with a Penguin-Putnam editor so I take the crosstown journey beneath the anvil of the sun along the entire river-to-river span of Houston Street (out-of-towners are cautioned that the street's first syllable is not pronounced like the city in Texas, but like the name of the poet A E Housman), a transverse of decrepit marvels too numerous to list, but well worth the walk.

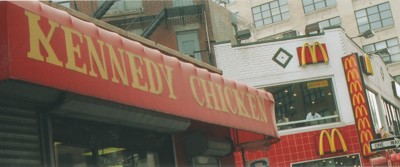

On my way to Hudson Street in the west Village, I learn to my dismay that the name of Kennedy has joined that of McDonald's in the world of junkfood chains as I discover a Kennedy Chicken nuzzled wing to nugget with a MmmmmcDonald's.

Kennedy Chicken: In the West Village, the authors learns to his dismay that his surname has joined that of McDonald's in the junk food chain

At 375 Hudson I meet Jeff Freiert at Penguin; after lunch we stroll to nearby St Luke's Place – a short, leafy, shady row of townhouses that hooks between Hudson and Leroy Streets. Here, across from a playground and the Hudson Park Branch of the New York

|

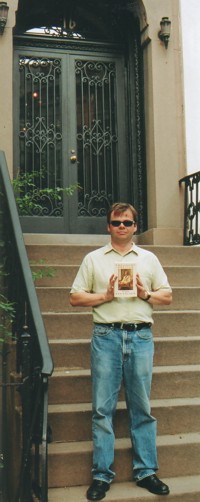

Public Library, livedTheodore Dreiser (1871-1945) at number 16 from 1922-23 while he was starting An American Tragedy, which he completed in a rented office at 201 Park Avenue. Since Penguin recently reissued Dreiser's The Financier from 1912 in a Meridian Edition, I persuade Jeff to pose on the townhouse stoop displaying the volume. Bill Morgan's excellent Literary Landmarks of New York (New York: Universe, 2002) tells me that a meeting was held on the parlor floor of Dreiser's house here in which F Scott FitzGerald, Horace Liveright, H. L. Mencken, and Carl Van Vechten discussed strategies for Dreiser's work to evade the wrath of the censors who had been plaguing him ever since Sister Carrie (1900) for “too vividly describing the seamier sides of life,” though perhaps also because of his championing of economic democracy; he died a communist in 1945. |

Penguin editor Jeff Freiert displays Penguin's re-issue of Theodore Dreiser's The Financier on the steps of Dreiser's old St. Luke's Place residence, which is now up for sale

|

No. 14 St. Luke's Place where Marianne Moore lived

|

the street in the library. In 1929 she moved to Fort Greene, Brooklyn, but returned later to the Village, when she lived at 35 W. 9th Street. In 1951 Moore's Collected Poems won the National Book Award, Pulitzer Prize and Bollinger Prize. A little sign on the door lintel of no. 14 proclaims “Peace and Love” in letters of modest size. It has always seemed to me that reading a single poem thoroughly is a job of work, and I recall as a student, having been assigned far more poems to read than I had time, strength, or inclination for, finding succor in the first line of Moore's “On Poetry”: “I, too, despise it…” |

|

Number 12 St. Luke's was the home of Sherwood Anderson. Morgan tells of Andersen's having to work up the nerve to knock on Dreiser's door to introduce himself, only to have it shut in his face after a curt greeting; Dreiser, it seems, was also shy before Anderson, but the two later became friends and Anderson also attended the anti-censor strategy planning session described above. No plaque commemorates Anderson's residency here. Indeed, the only sign in evidence is one advertising the house for sale – information from Jaime Farmer and James Roubul at 212-588-9490. Cell phone in fist I consider calling to ask the price, but decide against depressing myself. Jeff returns to work, and I am startled from my leafy shady reveries of famous poets and fictioneers by someone shouting out in the hot yellow sunlight on Hudson. A man is running, yelling, on the pavement across the street, while a red- |

No. 12 St. Luke's Place where Sherwood Anderson lived

|

Man dressed as tooth decay for Dentyne chewing gum commercial on Hudson and Bleecker streets

|

Avenue some 35 years ago, I do realize this is a film in progress and successfully resist the impulse to intervene, other than to join the melee with my own camera. The running man is wearing a costume I can only describe as resembling a six-foot turd. The camera crew take five and I sidle over to ask the costumed man if I might do a portrait. He appears quite pleased to comply and even grants permission to publish. I ask what the film is, and he tells me it is an ad for Dentyne. “You know? The gum? Cleans your teeth?” Ah! Not a turd but a personification of tooth decay, oral bacteria, gingivitis. |

|

Where St. Luke's meets Seventh Avenue is a short turn north from a cluster of small old-world-style streets crammed with literary history. “The narrowest house in New York,” at 75½ Bedford Street, between Commerce and Morton Streets, bears a plaque commemorating Edna St Vincent Millay (1892-1950) who lived here in 1923-24, the year she won the Pulitzer Prize for her poetry collection, The Ballad of the Harp Weaver. Among others who have lived in the house are John Barrymore, Margaret Mead, and Cary Grant. The plaque above the door quotes what are perhaps Millay's most famous lines, testimony to her relatively short life: |

75½ Bedford between Commerce and Morten Streets, home of among others Edna St Vincent Millay

|

It will not last the night.

But oh my foes and oh my friends,

It gives a lovely light.

Beneath the plaque an elegant lamp illuminates the door lintel.

Further along Bedford Street, at number 86, between Grove and Barrow, is a most remarkable place behind an unmarked door one would be likely to pass without notice unless forewarned – the restaurant, bar, former speakeasy which since 1928 has been frequented by more writers than perhaps any other single bar, or three, in New York, or anywhere: Chumley's.

Established by Leland Stanford Chumley, an organizer of the International Workers of the World (IWW), a former laborer, soldier of fortune, stagecoach driver, wagon tramp, waiter, artist, newspaper cartoonist and editorial writer, and taken over on his death by his widow, Henriette, from 1935 until her death in 1960. Since then, it has continued under a number of owners and managers without changing character.

What is now the main entrance at 86 Bedford was formerly an escape route during prohibition raids up to 1933 when the Volstead Act was repealed. In those days, the entry was through an archway at 58 Barrow Street, through the Pamela Court backyard to a very speakeasy-looking door within. When the cops came to raid, Chumley would detain them at the door while customers were advised to “86 it” – to take the 86 Bedford Street exit.

Chumley's has been host to James Agee, Djuna Barnes, Brendan Behan, John Berryman, Humphrey Bogart, Vance Bourjaily, William Burroughs, Willa Cather, John Cheever, Gregory Corso, Malcolm Cowley, e e cummings, Simone de Beauvoir, Floyd Dell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, James T. Farrell, William Faulkner, Edna Ferber, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, F.Scott FitzGerald, Alan Ginsberg, David Ignatow, Erica Jong, Buster Keaton, John F. Kennedy, Jack Kerouac, Ed Koch, Ring Lardner, Jr., Sinclair Lewis, Norman Mailer, W. Somerset Maugham, Mary McCarthy, Margaret Mead, Edna St Vincent Millay, Arthur Miller, Marianne Moore, Anaïs Nin, Eugene O'Neil, Henry Roth, J D Salinger, Delmore Schwartz, Upton Sinclair, John Steinbeck, William Styron, Dylan Thomas, Lowell Thomas, James Thurber, Edmund Wilson, and that is only a few of them. Acorrding to a rumor, furthered by David Yeodon and Roy Lewis, even James Joyce himself is said to have written a couple of chapters of Ulysses at a corner table here, though of course this is nonsense: Ulysses was completed before Chumley's was ever Chumley's; an even stronger argument against is that Joyce was never in New York City.

In her 1948 book, America Day by Day, Simone de Beauvoir wrote:

In Bedford Street is the only place in New York where you can read and work through the day, and talk through the night, without arousing curiosity or criticism: Chumley's. There is no music so that conversation is possible. The room is square, absolutely simple, with little tables set against the walls which are decorated with old book jackets. It has that thing rare in America: An atmosphere!

|

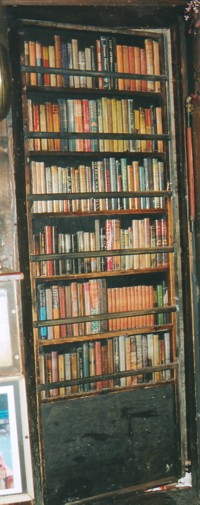

I myself frequented the place in the late '60s and early '70s – when I could find it. Usually I found myself there with a few glasses under my vest and rarely could find my way back sober. I recall arguing with a Danish girlfriend in the Bedford side alley, behind the door which is camoflauged as a tall narrow shelf of wooden book facsimiles, painted and carved with intricate verisimilitude. I don't recall the argument, only that I sulked in the alley for a time singing, for some reason, “Wi-ild ho-orses! Woulden drag me a-way….” While she sulked in Pamela Court, and my friends Jay Horowitz and Barry Brent sat inside looking for Ferlinghetti's “beautiful dame without mercy picking her nose in Chumley's.” Here, too, I ran into Gregory Corso on, according to him, his 40th birthday. He wore an army field jacket and was drinking a classic martini in a cocktail glass, straight up with an olive, and tried to sell me what he purported to be the first postage stamp ever |

Bookcase door of carved books in Chumley's

|

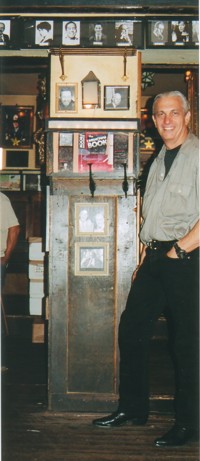

Today, I've found it after only a single martini and let myself in the unmarked 86 door, excuse myself past a tall man with long, distinguished grey hair and a beautiful woman with a tall exotic dog. Another man with a broom is sweeping around the bar, and I order a pint of Chumley's own pilsner. The tall man tells me the place is closed, but because I have been looking reverently at the book jackets on the walls, my order is filled, and he shows me around. His name is James Dipaola, and he seems to be the curator. He shows me the centerpiece jacket, titled The Unknown Book by Unknown Writer; where the author's photograph should be on the inside French flap is a small mirror – a

|

tribute to all the patrons who have labored to produce books that never saw print. The beautiful woman with the dog – a sleek-coated half English pointer named Maverick -- is Gina, a bartender studying at NYU. Jim Dipaola presents me with a pamphlet the size and shape of a bookjacket complete with French flaps, titled Chumley's, A Historic Narrative by Leland Stanford Chumley. Jim invites me to send him the jacket of my own most recent book along with a signed photograph of myself, preferably with a dog if I have one, so that he can add it to the collection on the walls. A few weeks later, I do so, and I hereby urge all reading this who visit Chumley's to investigate whether the jacket of Kerrigan's Copenhagen, A Love Story and/or Bluett's Blue Hours by Thomas E. Kennedy have been added to those venerable walls.

|

Jim Dipaola in Chumley's in front of the Unknown Book by Unknown Author

|

Chumley's many offerings of their own brands of draft

Reluctantly, I leave Jim and Gina and Maverick and the comfort of Chumley's, bound for Grove Court between Bedford and Hudson Streets where O Henry's daughter is said to have lived and which is said to have been the inspiration for the setting of O Henry's “Last Leaf.”

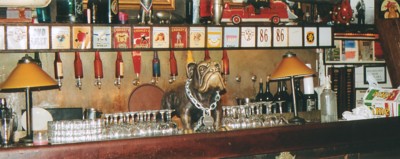

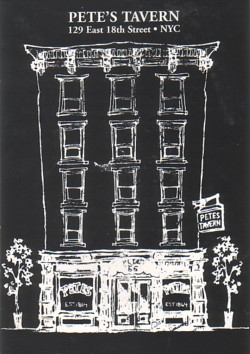

O Henry is of course all over the city, not least in the excellent Pete's Tavern at 129 East 18th Street that I won't have time to visit today, though often have in the past,

It is easy to imagine this as the place where Johnsy lay withering and waning in her bed, watching the leaves of an ivy vine on the brick wall outside her window disappear by the day with her strength and where the unsuccessful abstract artist, Behrman, refurbishes her will to live with a realistic painting of an ivy leaf on the wall – at the cost of his life; he falls from the ladder into the snow and, drunk, unable to rise again, he freezes to death. As all of O Henry, melodramatic, sentimental, contrived, moving and unforgettable – it sticks like gum to a shoe. The gate to Grove Court is locked behind a sign that sternly identifies it as private – an elegant place that once was a home for the struggling poor.

sitting whenever it is vacant at the booth by the front doors where O Henry wrote “The Gift of the Magi” – another of his unforgettable concoctions, five of which were filmed in 1952 as O. Henry's Full House, introduced and narrated by John Steinbeck and starring, inter alia, Marilyn Monroe. Pete's Tavern has been in continuous operation since 1851, first as a “grocery and grog,” during prohibition disguised as a flower shop. The kitchen is Italian, the food excellent, the martinis near psychedelic.

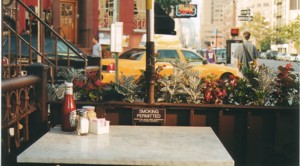

Across the street at the Village Cigar Shop, I purchase from a dour clerk a fresh, $8.00 Partagas, rolled of “100% tobacco” grown on Cuban seeds, which – while across the avenue yuppie types dine on expensive junk in the Gourmet Garage – I smoke at an outdoor table of the Riviera Café, nursing a bottle of Heinekin. I gaze across to the Segal sculpture, considering how at least some aspects of life have improved. On the table, a sign informs me that smoking is permitted, though the Surgeon General wishes to remind me it is a nuisance for others and a danger to myself. The Surgeon General makes no comment on the carbon monoxide fumes pumping from the pipes of scores of gasoline-burning automobiles that roll past just below my nose.

But I am now headed for Carpo's. I cross Sheridan Square at West 4th and Christopher where I stop to marvel at the irony of juxtaposing sculptures of General Sheridan in dark heavy bronze and two life-sized gay couples with white-painted finish by George Segal (1924-2000). These commemorate the birth of the Gay Liberation Movement in 1969 when the police tried to bust the Stonewall Bar at 51-53 Christopher Street and found, to their surprise, a gay clientele not willing to lay down and whimper. It took some doing and many years before the city finally allowed this memorial to be christened in 1992.

The only other customer is a young businessman at a nearby table. He sits over a juicy Riviera burger and speaks into a cell phone: “No no no, Chuck, no. You meet me here, you'll meet a tonna fuckin' people, ya know what I'm sayin'? Ya know what I mean? Don't meet me here.”

Riviera Café, W. 4th & Christopher Streets: Smoking is permitted but discouraged, inhalation of carbon monoxide inevitable

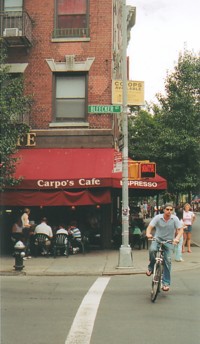

From Sheridan Square is a short walk over 4th to 189 Bleecker at Macdougal Street to Carpo's, formerly San Remo's, where I order a five-dollar Heinekin from a sweet-faced waitress and sit at a table out on the narrow strip of

“Are you dreaming of San Remo?” I ask. The brightness of their quizzical smiles tells me they are either out-of-towners or hard-core members of the post-911 corps of pleasant New Yorkers. I recently heard someone bemoan the passing of the rude New Yorker: If only someone would growl at me, I'd feel like things were safe again! The first 30 years of my life were spent here, and I know the New York crust covers a friendly heart; I wonder what the new New York smile might cover.

Bleecker sidewalk. Here in the free and open air, an endless fleet of yellow cabs excrete carbon monxoide into my air. I deserve it, I think, lighting a Petit Sumatra. The formerly smiling waitress descends upon me with wrath: “You cannot smoke here, sir!”

“Actually,” I explain feebly, “I don't inhale.”

“Well I do, sir!”

I stub out the lovely, barely-smoked Petit, apologizing. “Have a good monoxide.”

At a table behind me, two attractive women chortle, one blonde and the other auburn-haired, the latter wearing high heels and a polka-dotted summer dress that strikes me as 1950s.

I explain to the ladies that Carpo's used to be the San Remo Bar, opened by Joe Santini in 1923, a Bohemian headquarters until well into the '50s where the regulars included people like James Baldwin, William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Miles Davis, Norman Mailer, Jackson Pollock, William Styron, Dyan Thomas, and Tennessee Williams. Jack Kerouac was a regular for years, and it served as a model for the café “Mask” in San Francisco in his 1958 novel, The Subterraneans. According to Bill Morgan, the idea for the Living Theater was also born here.

“Oh!” says the polka-dotted young lady, “I'm studying acting myself. In San Francisco.” It turns out she is the daughter of the other young woman, from West Virginia, who confides to me she is 40. I had thought they were both around 27, but it seems too feeble a line to pitch. “Why don't you go knock on the door of the Actors Studio while you're here?”

“That's exactly what I told her,” the mother says. “Tell her to do it.”

Mother and daughter at Carpo's

“Do it,” I say, though actually I walked past it earlier in the day and the front doors were wide open, but with a chain across them on which hung a sign that read, This is not an entrance. Which I suppose could be interpreted in a number of ways. Considering how to tell about that, I am suddenly distracted by shouting on the other side of the street, and a cameraman runs past my table on the sidewalk. His red hair looks familiar. Then I notice a guy yelling and dressed up like tooth decay.

“You guys get around, don't you?” I call to the cameraman, who flashes a smile, and the West Virginian mother asks if I will introduce her, as she is a photographer herself. “I've taken some good pictures,” she says, “some of Shari, too, even where her ankles don't look so thick.”

Dos Passos and, Bill Morgan notes, “a very drunken Dylan Thomas.” In the late 1950s cummings was also once arrested for public urination on the Rue Git-le-Coeur in Paris, described on the French police blotter as ”un Américain qui pisse.” But that is another story.

But the cameraman and the running decay are already gone, and I finish my beer, bow and take my leave, on to Patchin Place at West 10th between Sixth and Greenwich Avenues. Here, at 4 Patchin Place, lived Edward Estlin Cummings (1894-1962) from 1923 until his death. I recall cummings outstanding line, “there is some shit I will not eat,” and wonder if I can boast the same. Among cummings houseguests here were Eliot, Pound,

Across the narrow way, at 5 Patchin Place, Djuna Barnes (1892-1982) lived reclusively for the last 42 years of her life. Her best known novel, however, Nightwood (1936), was written in Paris where she lived until the war forced her home.

Other literary residents of Patchin Place at various times included John Reed (1887-1920), “terror of the

Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) resided, author of the 1883 sonnet, “The New Colossus,” which contains perhaps the most quoted lines of any American poem, inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty:

industrialists”; John Masefield (1878-1967) in the years before his four decades as poet laureate of England; the Irish writer Padraic Colum (1881-1972) and Janes Bowles (1917-73).

Further north and east at 14 West 10th between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, at the beginning of the 20th century lived an author not commonly associated with the Big Apple: Samuel Langhorne Clemmens, a.k.a. Mark Twain (1835-1910). In fact, according to my guidebook, it was in New York that Twain first donned the white serge suit that became his trademark.

These days when one enters the country by flying ship, the poetry of welcome takes the form of questions printed on a green form about whether one suffers from contagious diseases or mental illness, whether one has ever been arrested for a serious crime, engaged in espionage, sabotage or moral turpitude: answer yes or no, please.

“Give me your tired, your poor,/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,/The wretched refuse of your teeming shores,-/Send these, the homeless, tempest-tosst to me,/I lift my lamp beside the golden door.”

At 23 East 10th at University Place in the Albert Hotel's room 2220 from 1923 to 1926, Thomas Wolfe (1900-38) stayed while he taught writing at NYU and worked on Look Homeward Angel – “ a stone, a leaf an unfound door…” In his Of Time and the River, The Albert appears as the Hotel Leopold.

Wolfe – and many other writers, artists and musicians – also stayed for a time at the Chelsea Hotel between 7th and 8th Avenues at 222 23rd Street. The Chelsea's many celebrated guests included Arthur Miller, Dylan Thomas, Mark Twain, O Henry, Edgar Lee Masters, James T Farrell, Mary McCarthy, Brendan Behan, Arthur C. Clarke, Nelson Algren, Nabokov, Yevtushenko, Burroughs, Corso, Ferlinghetti, and the punk rocker Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols who murdered his girlfriend in Room 100 here before ending his own life, although there have been recent assertions that both were murdered by a third person.. Bob Dylan, too, in his song “Sara” on the Desire album, reports having written “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” in the Chelsea.

Among the fiction of Thomas Wolfe is the extraordinary story “Only the Dead Know Brookyln.” It seems to me only the dead could know the immensity of New York's literary history. I give up, refrain from visiting Kerouac's apartment at 454 W 20th between 9th and 10th, or Auden's at 77 St Mark's Place between 1st and 2nd or the statue of Washington Irving a Irving Place and 17th Street.

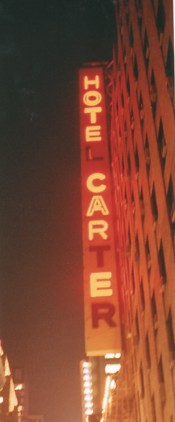

Instead I head back to my hotel, still on foot, wading through the heat of the darkening evening to the Hotel Carter on 43rd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, a family-owned hotel recommended to me by Mike Lee of the Cape Cod Voice, across the street from the New York Times offices.

Once known as The Dixie, the Carter was subject of an April 1986 Village Voice exposé by Laurie Stone entitled “Heartbreak Hotels,” about the more than 3,000 homeless familes temporarily housed in run-down, overpriced hotels. Clearly, the Carter has seen better days as well as worse days, but on the Manhattan hotel market it can hardly be called overpriced today. My room on the 21st floor costs $89 a night and has a view, or a scrap of a view out the bathroom window, of the Hudson River. I am in room 2131, which is about 7 by 15 feet with a ten-foot ceiling, a walk-in closet which looks like a basement utility room, deckpainted green. There is a good bathroom, three windows, three good mirrors – one strategically positioned at the foot of the king-sized bed for those who like to watch themselves en embrace. Above the bed hangs a single, faded, framed print that seems to want to simulate Paris, and another view out the windows in the sleeping room down to the traffic on 43rd and Eighth.

At night when the tall narrow neon sign that climbs the outer wall blinks on, the name of the hotel changes to HOTE CAR E, the 'L', 'T' and terminal 'R' having burnt out a couple of years before. It occurs to me that if the E's go, one at a time, in succession, the hotel will assume, by turns, the names HOT CAR E and HOT CAR, maybe at some point it will be just HOT.

Hot it is tonight as I greet the night manager, Abdul, seated at a desk and swivel chair in the middle of the broad dim lobby. He knows I am writing about New York and invites me to join him in the elevator to visit the ghost floor on 24, peopled now by old laundry wagons full of discarded cables and bedding, old mattresses and other rubble. A sign on the wall still advertises the defunct Circle Bar and Lounge and Terrace Restaurant (Dinner from $3.75, lunch from $1.25), but the stairway to the roof is impassable, blocked with chunks of plaster and refuse.

Just as well. I retire to my Bogart noir room with its battered mismatched furniture, a bed table with a drawer but no pull knob, a plastic chair. Thank god it has functioning A/C. I drink a tepid cocktail of Stolichnaya from a cellophane tootbrush glass and munch a turkey curry sandwich purchased from the 24-hour deli that adjoins the lobby, watching kids skateboard a few floors below on the roof of a building across 43rd.

It occurs to me that those kids' New York is one I will never know. And perhaps they will know little of the New York I see. William Sidney Porter (1862-1910), aka Oliver Henry, aka O. Henry, wrote his New York tales of The Four Million (1906), and each episode of the 1960s TV series about New York, The Naked City, concluded, ”There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them.” It seems to me now, watching those roof-top skateboarders I will never know, that perhaps there are eight million New Yorks.

No one will ever know more than a tiny fraction of them.

Chumley's, A Historic Narrative by Leland Stanford Chumley, published by Eight Palms Ltd (pamphlet, 1988).

East Village Map Walking Tour & Poster. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Ephemera Press (www.ephemerpress.com

Historical Atlas of New York City, Erick Homberger and Alice Hudson, Cartographic Consultant. New York: An Owl Book, Henry Holt and Company, 1994.

Literary Landmarks of New York, Bill Morgan. New York: Universe, 2002.

New York: An Illustrated Anthology, Compiled by Michael Marqusie (Introduction by Jay McInerney). London: Conran Octopus Ltd, 1988.

New York Book of Bars, Pubs & Taverns, David Yeadon and Roy Lewis. Ontario, Canada: Hawthorn Books, 1975.

New York Literary Lights, William Corbett. Saint Paul, Minnesotta: Graywolf Press, 1998.

New York Unexpurgated by Petronius. New York: Grove Press, 1966.

[copyright 2004, Thomas E. Kennedy]