THE WIND BLEW IT AWAY:

Memoir of a Summer Day on the Contrescarpe

Thomas E. Kennedy

-For Walter Cummins

Place de la Contrescarpe is a square, a circle really, of cafés – Café de la Contrescarpe, Cafe des Artistes, Café des Chopes, recently renamed Café Delmas – around a plashing fountain where French clochards lie sunning themselves in their rags, arms wrapped about their bottles. Only today there Is little sun. There is chill and damp this Bloomsday plus one, but I am thirsty nonetheless, having witnessed hundreds of sweating Parisians run a marathon through the dog droppings in the Bois de Boulogne.

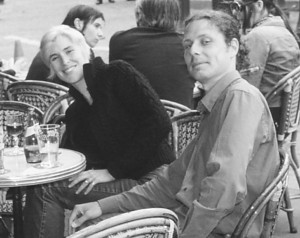

photo by Ron Davis

As soon as we find a table at the Café de la Contrescarpe, I seek the waiter's eye with great purpose and say loudly enough not to be ignored even by a French waiter, "Une grande pression, s'il vous plaît, monsieur!" Useful words for a beer drinker in Paris to know. He does not ignore me, but the tilt of his visage speaks volumes: All in good time, my good sir.

With us at the table so far are Ron and Lauren Davis. Lauren is a Canadian fiction writer, whose background is a brew of Irish, Objibway, French, and Mohawk. Lauren's first collection of stories, entitled Rat Medicine, appeared last year from Mosaic Press in Canada, and her first novel, The Stubborn Season, is scheduled for spring 2002 from HarperCollins Canada; set in the 1930s, it is an exploration of madness in the family and how the mental illness of one member affects the whole. Ron is a business executive and a photographer of impressive talent – I could see the source of some of his photographic inspiration that morning over breakfast on their balcony, gazing out at the rooftops of Paris from the Eiffel Tower to Sacre Coeur. They are a handsome couple, a muscular dark-bearded man and a slender, light-eyed, graceful woman. Manolita Farolan, a psychiatrist and fiction writer from the Philippines via Geneva, has joined us as well, and now Walter and Alison Cummins appear.

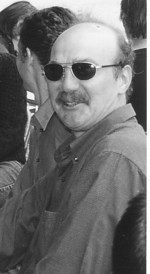

photo by Thomas E. Kennedy

Walter Cummins is the element around which this group of writers, poets, and editors has crystallized on the Contrescarpe the day after what had been the 97th anniversary of Leopold Bloom's famous walk through Dublin – which I involuntarily celebrated in a dim hotel conference room in Sliema, Malta, listening to the representatives of fourteen organisations of the European Union debate whether to kick France out for non-payment of dues. But that was yesterday. Now I've fled to France to celebrate not Bloom but Cummins

An Iowa graduate from 1962, Walter studied there with Philip Roth (then fresh from the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus), George P. Elliott (whose "Among the Dangs" I recall marvelling over as a student at CCNY four decades ago), R. V. Cassill, Vance Bourjaily; his fellow students included Charles Wright, Mark Strand, Mark Costello. He graduated the year before Andre Dubus and Raymond Carver came to town. He has edited The Literary Review at Fairleigh Dickinson University for the past eighteen years in addition to producing a considerable body of fiction – a hundred stories, in fact, a number we have to pry out of him during the course of the conversation; as soon as he admits it, he turns the attention from himself to someone else, a modest, gentle man who sports a Cape Cod fisherman's beard. His forte as an editor is the art of encouragement. More than half the dozen people present or about to be have been published by him – essays, stories, poems, whole features. He picked one of my early stories for the annual award presented by his journal, and in the years that followed we have collaborated on many theme issues. This is only the third time we have met in person, always briefly, although we are in near daily contact by email between our respective offices in New Jersey and Denmark, our business communications growing more personal as we share our appreciation of jazz, travel, beer...

photo by Ron Davis

|

|

Now the beer and wine and other drinks are coming, and I am happy with my golden Stella Artois as three representatives of the Paris-based American literary journal, Frank, appear on the square. The editor, David Applefield, is the eponymous force behind David Applefield Productions, the imprint which has published Lauren's first book and a number of others, including the quirky novel Our Lady by Dale Gershwin, about a plot to blow up the Notre Dame, and a recent novel by a former high level U.S. spy, Eric Jordan's Operation Hebron. Applefield returned from Mali the evening before where he interviewed the president of that country for no other reason I can discern than that he had seen the opportunity to do so. In addition to his numerous literary involvements as editor, publisher, novelist, and his sometime role as a prizefight announcer, Applefield has interviewed an astonishing array of people including Vaclev Havel, Robert Coover, Rita Dove, Samuel Beckett, and his collaborator John Calder, who has published eighteen Nobel laureates and over five thousand books in the past fifty years.

I am fond of quoting something Applefield got Raymond Carver to say when he interviewed him in the 1980s – to the effect that people are no longer interested in fiction that is concerned with innovation; readers are now interested only in "the real things that really matter to real people." When I was writing literary criticism a dozen years ago, I used that statement as an indication it might be time to burn your Kafkas. Or as Donald Barthelme put it, "Postmodernism is dead. Get out fast before your stock crashes."

Applefield is currently in line to interview Fidel Castro, with whom he has a connection through a Cuban artist resident in Paris. But now the honor of a David Applefield interview has befallen me. He has the page proofs with him in the bulky bag of literary things he lugs about, Frank's first "Literary Conference Call" – a double interview with novelist Duff Brenna (The Book of Mamie, The Holy Book of the Beard, Too Cool, The Altar of the Body) and myself, with chapters of our latest novels thrown in. Now at last I see the proofs upon which his two associates – Ethan Gilsdorf and the beautiful Lisa Pasold – have lavished generous attention. They cleaned up the graphic material I supplied, including a picture of a very hard to photograph neon chicken laying neon eggs that adorns a dark wall in my Copenhagen neighborhood. They have also selected quotes to highlight as side-bar eye-catchers, such as:

I want to know

what has happened to me

in my life.

"Did I really say that?" I ask.

"Did Tom really say that?" David asks Ethan and Lisa.

"He really said it."

"I'll tell you what happened," I say. "I stole breakfast." David smirks and says nothing. We are bound by a guilty secret from a dozen years before when we biked through the Dutch countryside and stopped with empty pockets to take our morning meal in the breakfast room of a luxury hotel and escaped like two ageing desperados.

"What about the vodka ad?" I ask. David has been angling to sell Absolut Vodka a back cover advertisement focusing on the fact that my novel chapter is titled, "The Sacrament of Vodka." He has proposed to have a picture of me in the shape of a vodka bottle – or perhaps a vodka bottle in the shape of me – above the caption, "Absolut Kennedy! There is only one god and one vodka!" I am crazy about the idea, picture a framed glossy of it adorning my living room, but there is one problem: the one vodka the character in my novel refers to is Stolichnaya; in fact, he questions the credentials of Swedes to burn vodka at all.

"The ad didn't fly," Applefield informs me with a smirk.

His associate, Lisa Pasold, a tall, slender, striking woman in slinky jeans and red, pointed cowboy boots, is about to launch her own magazine, Lieu a publication about place; each issue will inhabit and explore a different architectural environment. "Does a place have a soul or a memory?" she asks. "This is a type of haunting; a raising of the past and the future through creative interpretations of a building's life. How do we hear the voice of a building?" She is also a free-lance journalist, currently completing a novel about art forgery based on her experiences as an artist's model and art critic. photo by Thomas E. Kennedy

There is talk at the table about Lisa's husband, Bremner Duthie, a classically-trained singer, a baritone. Lauren Davis told me over breakfast about his performance in his own musical theater piece, Whiskey Bars, which portrays the imperfect life of a performer interpreted through the music of Kurt Weil, including both Bertold Brecht and Langston Hughes lyrics. The show has toured Canada and is now on its way to New York, and Lauren tells about the bravado of Duthie's opening scene, coming out on stage fresh from the shower, wrapped in a towel, to don jockey shorts and nothing else while he sings a satirical version of a Nazi drinking song..

Ethan Gilsdorf is in his early thirties, a poet and film critic, free-lance journalist, who has just published an article in Poets & Writers entitled "Revising the Myth: The Expatriate Writer in Paris" (May/June 2001) – very appropros. I am fascinated by these people, the new Paris expatriates, living out the dream of a life so many generations before have tried, or merely dreamed of. And what better place for a gathering of such dreamers, in this circle of cafés where Ernest Hemingway sat to work on The Sun Also Rises, around corners from two of his earlier residences (74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine and 39 rue Descartes, the hotel turned restaurant where Paul Verlaine died in 1896 and Hemingway lived from 1921-25) and around another corner from a house where Descartes spent three years of his writing life.

Hemingway's A Moveable Feast tells about those years, a beautiful book marred, I think, only by his inability to resist settling old scores. But here we sit in his old neighborhood, a dozen expatriates ranging in age from early thirties to mid-sixties, five generational decades of writers, and perhaps I am naive, but I feel certain there are and will be no scores to settle here, nothing short of pleasure at our coming together this day, no animosity of the sort Hemingway apparently felt for Gertrude Stein, Ford Maddox Ford, others he learned from and surpassed in celebrity. Perhaps we're not important or determined enough to engage in feuds or grudges. Or who knows? Perhaps one day some of us will despise and scorn one another, hurt by our own success or the lack of it or the success of others.

I rise to take pictures, and the poet Ellen Hinsey -- whose face makes me recall a description in Hemingway's Feast, "She was very pretty with a face fresh as a newly minted coin if they minted coins in smooth flesh with rain-freshened skin, and her hair was black as a crow's wing and cut sharply and diagonally across her cheek." -- says, "I hope they're black and white."

"Right. These will be pictures footnoting the nostalgic books about Paris fifty years from now."

"Har! In your dreams!"

A winner of the Yale Younger Poets Award, Ellen has been in Paris for thirteen years with her partner Mark, who is director of new media at the Asian Arts museum, Musée Guimet. She is currently, simultaneously, working on a novel and her third book of poems.

photo by Walter Cummins

Across the square appears David Poe, tall and rangey, one-armed, with his angular Polish face, high forehead, and dark moustache. He waves, heads for our tables. Poe it was who first showed me this square half a decade ago, an expatriate married to an economist named Candy who works for the OECD. He is from Buffalo, studied at Syracuse with George P. Elliot, Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolf, dormed with Ralph Lombraglia, and is a fine writer with a drawerful of short stories he is too shy to publish, all about American expatriates in Paris. I saw one which won the Prairie Schooner prize a few years ago, about an American infatuated with the wife of his building's concierge, and I managed to squeeze another out of him for Cimarron Review, when I was International Editor there, another compelling piece about basketball and racism in Paris. I know he has a good dozen others which he refuses to publish. He wants to rework them one more time. I fear he will hammer and chisel them until nothing remains but a scatter of stone dust.

Poe has only one hand, though he can do with it more than I can with both of mine. He literally single-handledly renovated his two hundred year old house on the Seine in the tiny village of Vieux Port, north of Paris; he travels around the countryside in search of healthy wood from the same period as his house to replace rotted beams and rafters, and when I see what he has done with the house, it occurs to me perhaps those stories are also near perfect by now. (Editor's note: Another of Poe's stories will appear in the next issue of Story Quarterly.)

When I visit him in Vieux Port we sit out on his deck and drink beer or wine or cognac and watch the Seine stream past. We have a tradition of sharing strong drink near flowing water, dating back to our first meeting at a writers seminar in southeastern Netherlands a decade ago. We sat every day in the August sunlight on the bank of the River Maas drinking glowing golden pints of Amstel and Oranjeboom and vowed to meet at least once a year someplace where there was water and repeat the experience.. And we have done that, every year – in Belgium, Portugal, Denmark, France, Cape Cod – always raising our glasses to big Mike Lee who was with us then and joins us whenever he can. Mike, with his two purple hearts from the Nam, is a humorist whose Cape Cod columns about encounters with Brigitte Bardot and Larry King and Norman Mailer deserve national syndication..

Now Dave Poe and I happily clack our schooners of Stella, nod to the burbling Contrescarpe fountain and drink. Poe's voice is deep and there is humor in his face. He also has a sense of humor about his so-called handicap. Visiting Lourdes once as a tourist he saw the place where healed people hung the discarded accoutrements of their disabilities on a line by the sacred source – those who had been made to walk leaving behind their crutches, those who had been made to see leaving behind dark glasses and white canes. Dave had in the trunk of his car an old hook he no longer needed or used, and he hung it on the branch of a tree nearby, a puzzle for the faithful to decipher and marvel over.

In Holland, a beautiful young student became fascinated by his hook. She used to trail along after the old salty guys when we went to sit on the bank of the Maas in our favorite café where the 90-year-old owner, Nellie, now alas no longer whinnying with us, served us pints of cheerful beer, and the river flowed across the flat yellow countryside beneath the clear blue sky. The girl was always near Dave that summer, always touching his hook until finally one evening, he had enough. "Hey! Cut it out! I'm getting blue hook!" He also refers to the instrument as the world's most expensive roach clip.

Janet McDonald appears now to give a hug, author of the memoir Project Girl, published to great acclaim by FSG in 1999. Walter is about to publish my interview with her, which I felt compelled to do when I met her by chance in Copenhagen, a black woman from the Brooklyn slums who lives in Paris bumping into a white guy from working class Queens who lives in Denmark. I never had a gun, never took heroin, but I hit the bottom of another well in a kindred world governed by violence and racism and stupidity. Janet's second book is due out from FSG in the fall, Ellen Hinsey's second poetry collection from Wellesley next year, Lauren's novel next spring, and my book of essays from Wordcraft this fall. We lift our glasses to these four miracles – every serious publication in this world of television gab and action films is a wonder, every published book a miracle.

photos by Thomas E. Kennedy |

|

Janet grew up in the Brooklyn projects, came from a life which at one point found her stalking the streets of New York City with a pistol in her belt and murder in her heart, cutting college classes to score heroin, surviving a rape, but she managed to rise above very hard conditions to win degrees in French literature from Vassar, journalism from Columbia, and law from NYU. She now lives in Paris where she works as a lawyer and is completing her third book for FSG, and she is now on her way to the Sunday evening Paris Connections Soiree Dinner at 35 quai d'Anjou, Paris 4, where she will be Patricia Laplante-Collins guest of honor. Paris Connections is an event similar to the Sunday night dinner gatherings arranged by Jim Haynes, at his Atelier A2, 83 rue de la Tombe-Issoire, Paris 14 (telephone first – 4327-1767) – Haynes also publishes Hand-Shake editions (the contract is a hand-shake). Two places to eat for a reasonable price and meet interesting people.

Janet leaves us, and as we drink and talk, we look up from time to time for others who might be joining us. Several have come from behind to lay surprise hands on our shoulders. "Are you...? Aren't you...? Is this...?" This must be the place. Walter and I are on the look-out for the poet Julie Fay who gave us a fascinating poem about the word "interstitial" and an essay for our Poems & Sources issue last year and whom I have never seen, though she taught my daugher poetry for a month at Converse College. Little do we know that at some unfortunate point when we are not sufficiently alert, she circles the group, looks, decides we are not them after all, and leaves again.

A wind whips across the café, wallops up under the awning and throws a cascade of rainwater down its sides. From one of the café tables, a collection of bills the waiter has delivered with each round of drinks, tucked in under the narrow chrome edge of the formica table top, are grabbed by the wind. They fly up like confetti, and several of us lunge for them. We manage to salvage most, though I see at least one scooted away between legs, under tables, out to the square where the clochards lie with their bottles in the grey light.

It is time to pay. People are leaving. A tug of regret touches me. It is too soon for this to end. We've hardly begun. The waiter gathers the little pieces of paper and shuffles them through his fingers, inspecting them glumly.

"Monsieur!" he cries. "One of them is meesing!" His comment is directed to me. Clearly he has decided I am responsible, the loudmouth who demanded beer so ungallantly at the beginning of the day. I remember Julie Faye telling me that another celebrated poet who might be coming with her had suggested 3:00 p.m. was not an appropriate hour for drinks. It was only appropriate for tea. Drinks must await l'heure bleu.

"I'm sorry," I explain to the furious waiter. "The wind blew it away."

He smolders. "C'est impossible! C'est moi qui est le patron! Monsieur, you cannot come here and do this thing!" He slaps the little stack of bills against his palm and fumes. Dave Poe huddles with him, and they find a solution: To take an average of all the remaining bills and let that be the amount of the one that has blown away. I give the now contented waiter my master card, gather up the franc notes and coins heaped before me by the others. The waiter returns with a pen and mastercard voucher for me to sign and says, "Monsieur. Je regrette. Your Mastercard. Pft! It is gone."

"Gone!"

He nods solemnly. "Oui. Pft! Gone." Then he laughs happily, pleased with himself, vindicated. "Zis ees my joke."

Eight of us stay on for dinner at Maison de Verlaine at 39, rue Descartes where in 1895, the year before he died, Verlaine wrote the preface to the first edition of the complete works of Arthur Rimbaud, who'd died four years earlier, at the age of thirty-seven. We are all happy with our three-course ninety-nine franc menus that include un petit pichet de vin rouge. At least I am happy, and the others seem so too. Alison Cummins looks radiant, and Walter is grinning broadly in his white Cape Cod beard. Ron is smiling and Lauren is smiling. Perhaps I am drunk. Ethan's wife, Isabelle Sulek, who has spent the afternoon at the cinema, joins us. A slender dark-haired woman she is a student of West African dance at a studio in Ménilmontant, the Centre Momboye, taking classes in Guinean, Cote d'Ivoirian and Malian dance. I wish that I could see her dance right now, but am amazed to learn that the film she just came from is one I saw in 1960 when I was sixteen and which I was certain no one else in the world would ever remember, Paris Blues with Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier. Somehow she gets me explaining why I think Pasolini's Oedipus Rex is a masterpiece: because he takes everything that Sophocles summarized and dramatizes it. He pulls the story out of its classic concentration, takes the drama away from the moment of narration and tells it from start to finish. The passion and violence and fear and love become immediate rather than retrospective,experienced rather than explained. Apparently I am sober enough to refrain from exclaiming, Shown not told!

As I expound, I notice that the drippings of the candle on our table uncannily resemble Rodin's Citizens of Calais and wonder if I have had one pichet de vin rouge too many, ask if others see it, too, and enough agree with me that either it is true or we have all had too many pichets.

photo by Thomas E. Kennedy

--where in 1895, the year before he died, Paul Verlaine,

wrote the preface to the first edition of the collected

poetry of Arthur Rimbaud, who had died four years before,

at the age of 37. Hemingway lived here as well,

on the 6th or 8th floor, from 1921 to 1925.

Outside we photograph the plaque which tells that Verlaine died and Hemingway lived there, and I remember in A Moveable Feast Hemingway telling how he lived on the 6th or 8th floor there one winter of the early twenties and was afraid to take the chance of lighting the fireplace for fear the cold chimney would not draw and would leave him broke and cold instead of just cold. Instead, he goes to a café to write and spends the fuel money on rum St. James which he drinks as he writes. The memory of reading that fills my chest with longing and pleasure for an experience unique to this city and still here so many places, in so many cafés, amidst the history of all the writers and artists who have come here--Kerouac, Burroughs, Ginsburg in the Beat Hotel at 9 rue Git-le-Coeur, the wild young Rimbaud not yet turned gun-runner, still a poet, at 10, rue de Buci, Van Gogh at 54 rue Lepic with his brother Theo, Proust at 102 Bd. Haussmann, Colette at 9 rue de Beaujolais, Dali at 7 rue Gauget, Victor Hugo at 6 Place des Vosges, a beautiful square, Balzac living under the name of M. de Brugnol at 47 rue Raynouard, Ezra Pound on rue Notre-Dame des Champs, the Fitzgerlands at 14 rue de Tilsitt, the house at 7 rue des Grands Augustins just off the Seine where Balzac wrote "The Unknown Masterpiece" and Picasso painted Guernica , the apartment at 17/19 rue Beautreillis where Jim Morrison died just thirty years ago this year, on July 3rd.

I do not want us to part yet, propose that we go and look at the Hemingway apartment on Cardinal Lemoine and at Descartes' home.

The old Hemingway apartment, up the street from where poet Carolyn Kizer summers, is now above a travel agency that has borrowed his name, there where the Bal Musette once was that Ford Maddox Ford drew a map for Hemingway to find despite Hemingway's protests that he lived right on the third floor of the building.

Down the street we stand before the Descartes maison where a plaque tells about the three years it was the philosopher's home. Here we are surrounded by taller, darker buildings than on the Contrescarpe, and we stand there for a time, milling about, talking. It is past eleven. In a corner behind us, another tall, narrow, windowless building looms strangely above us. We decide to have one more nightcap in the café that used to be the Café des Chopes where Hemingway worked on The Sun Also Rises.

As we shuffle up the dark street where Descartes once trod, toward the lights of the Contrescarpe, I delve into my memories of Philosophy I, The Sphere of the Doubtful, and recite, "Let us imagine that instead of an all-knowing benevolent God, our world was created by an evil genius whose sole intent is to deceive and trick us..."

"But monsieur," says Dave Poe, "It was!"

"You mean the world is evil?"

"Does that surprise you?"

"O seasons! O châteaus"

And we laugh and head toward the lights and the drink.

photo by Ron Davis

Isabelle Sulek, and Ethan Gilsdorf

[copyright 2001, Thomas E. Kennedy]