|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen |

Giving Up the Money

Essay by Thomas E. Kennedy

Photos by Alice Guldbrandsen, Nina Juhlin, and Gorm Valentin

Subjective scenes from Copenhagen's Poetry Day, Frederiksberg Garden, Aug. 27, 2006

The afternoon seems to start with a spark of triumph. For an hour, the weather has been dry. Even a few shreds of sunlight defy the dark clouds overhead, and Bob and I have been drawing them in, altogether maybe 100 to 150 people in groups of ten to twenty.

It's up to the individual poet and his sense of timing to grab them, trap them, make them stop and listen. Sometimes they stop with uncertainty or because they are polite or timid or kind. You usually lose those ones after a minute or two unless you seize them, fix them with your crazy eye like the Ancient Mariner and make them listen. We have to fight the language, too. Danes expect, reasonably enough, to be read to in Danish. They can tolerate English, but the mother tongue in Denmark is, in fact — and this should come as no surprise — Danish.

Danes don't shock. They smile. They laugh. They like it. They love cunt. (One fine-looking young woman says drolly, “He's stuttering.”) I don't even have to worry about offending parents with small children — all the Danish kids know and love all the foulest American words thanks to our movies and rap.

The odd lone wolf shows up now, wrapped in a black plastic garbage bag, looking for a poem. We provide a sandwich, a cup of wine, but they want words, too, poems. We read to them, alone or in twos and threes. Beautiful die-hards that have come to hear poetry — rain, shine or Ragnarok. We stand under the violet umbrellas in wet shirts, everything dripping, reading until, at last, the message comes from the command center, calling all poet troops in to dry off and get drunk, all hundred-fifteen of us

There is only one problem. I, too, am a member of the Board. I work on the arrangement of all this with the chairperson and both the lawyers and all the other poet members of the Board. My work is unpaid, and I have no doubt that my name was picked fair and square, but I also know, as surely as I know the human heart is powered by equal parts of yin and yang, that some, perhaps many, perhaps even most people in the audience are going to smile and think, Fixed! It's bloody fixed! I might even think that myself if I weren't such a trusting guy!

I can see that she is startled. “Can't you use the money yourself?”

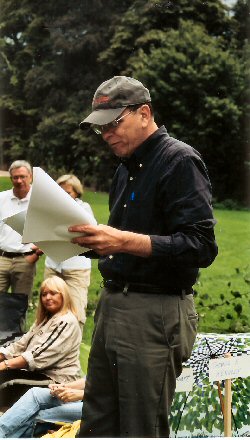

It is raining in New York and New Jersey. It is also raining in Kansas City. But here in Copenhagen —Frederiksberg rather, which is pretty much the same thing, Robert Stewart and I are stationed together before a gravel path, out on a broad plane of grass in front of a grassy knoll that prickles with trees, he in his grey New Letters Magazine cap, I in the leopard skin pillbox hat Alice gave me for my sixtieth birthday two years ago. Now it is Bob's turn for the six-oh, and this is how we celebrate, reading poetry aloud for three hours nonstop to a mass of people.

We are not the only ones. This Garden is huge, and there are poets everywhere, under trees, on the grass, in front of benches and lakes on whose banks herons strut, both the famous and the less known, young and old and in between, men and women, Danes, Americans, Germans, Muslims, you name it, over a hundred of us. Staked in the grass before us, two signs announce our names, blue-inked in fat felt pen.

Kennedy reads on the Green, Stewart in the bullpen

We take the grass alternately for five or ten minutes apiece, doing the carny act that is required to draw them to you. Here on Poetry Day — last Sunday in August every year for the past five — you've got a potential audience of thousands, but they don't come in to you and sit down in a theater or café and wait for you to stand up on a stage and read to them. Here the poets are ranged around at different posts throughout this huge garden, and the audience comes strolling past at its own pace, each holding a map that shows who is reading where. Some have come to see only specific poets. It is our job to change their minds.

Kennedy emotes for the public

Stewart does Kansas City word blues

My trick this year is to lead with a boldly aggressive poem that starts:

What is it that you most want me not to say?

I do not know what you are most afraid of.

What taboos tatooed on your brain

Do you most fear hearing break?

Do you know? I don't. Tell me!

What if I say cunt?

What if I scream it hard and ugly?

Cunt! Cunt! Cunt!

Will that do it for you?

By now, we have 20 or 25 people around us, and after ten minutes, I turn and say, “Ladies and gentlemen, Robert Stewart from Kansas City, Editor of New Letters magazine! And free sandwiches and wine after he reads, compliments of University of Missouri!” Actually the sandwiches are left-over from the party we threw yesterday, but the name of the university seems to lend elan to the offer.

Bob is on the crowd at once, chanting Midwest word-blues for them.

Things are great. We've got our honeys with us, a few friends on the grass backing us up with their presence, food, drink. I've been worried about all the things that could go wrong, but begin to relax with the fact that Bob and Lisa have flown thousands of miles at my invitation to be here. Everything is going to be fine.

Then there is a slow, low ripping sound as the skies tear open and rain pours down.

“When it rains this hard,” somebody says, “it doesn't rain for long.”

“That's right!” I shout over the pounding deluge.

We open our violet-colored, official Poetry Day umbrellas and continue reading. It continues raining. It rains. And it rains. People are no longer stopping as we boldly march forward flinging poetry at them. People are running away, jumping under trees, huddling, disappearing behind the sheets and sheets of water that hang around us.

Lene Poulsen and assorted poets and audience listening to poetry in the rain delivered by Jonas Gülstorff, Andreas Bennetzen, Michael Sandwick and Lennox Raphael, all of whom later shared one half of the popular prize

Lene Poulsen flanked by Samuel Bobie og William Lgekum, drummers from Ghana. The drums are in shelter beneath the blankets. They had sat at the entrance earlier in the day drumming vigorously to draw the crowd

The sandwiches we brought are wet. The clear plastic bags of Alice's unparalleled meatballs, of which she made 300 for yesterday's reception, are fogging up. Rainwater baptizes our plastic cups of wine, our beer, soggies our cigarettes and our butts, too. Our poetry is soaked. The pages stick together. Rain runs from the tips of umbrella frames, from the tips of noses. I notice a copy of Bob Stewart's poetry collection, Plumbers, floating in a pool of water in the seat of a folding canvas chair. (This collection will later turn up in the hands of the Chairperson, Lene Poulsen, who will incorporate it as an official Poetry Day 2006 souvenir. As of this writing, I am told that it is still not dry.) Robert Stewart does his rendition of "Readin' in the Rain"

Robert Stewart does his rendition of "Readin' in the Rain"

We straggle back towards the Knights Room, over by the main entrance, where the post-festival festivities are to be held, with various ceremonies and the annual dinner. We have quit the fields of poetry an hour early, however, so there will be a two-hour wait for the dinner. But we can drink. There is beer and there is wine and there is elderberry juice. It is dank and close and dark in the Knights Room, but we are so happy to be indoors that we don't care. Even if we are still wet. It has rained through the shoulders and sleeves of my jacket to the shoulders and sleeves of my shirt to my undershirt, and my situation is not as bad as Alice's who is wet through to her underpants and further in. No matter, we fling what we can of wetness from us and clank beer bottles with fellow poets. We are all wet. None is dry in this congregation. Nothing to do but laugh about it. I raise my bottle to Niels Hav and his concert pianist wife Christina and their little girl and to Henrik and Ellen Nebelong, to sweet Gunvor and to Peter and Frederik, to Lotte Inuk and Marianne Larsen and Sam Fleischer and to Kenneth Krabat, who is wearing a hat that is even weirder than mine.

The rain stops for a few moments, and we are driven outside to group up where the great Danish photographer Gorm Valentine stands on a balcony like a general commanding the amoebic body of 100 poets (like an army of cats) to assume a form that can be fitted into the scope of his lens. Being not tall, I take a place near the front rows and hear a woman mutter behind me, “There's the man with the hat,” but I refuse to doff my leopardskin pillbox.

Inside again, we take a seat in the theater upstairs where the ceremonies are about to begin. Is everybody in? Is everybody in?

Lene Poulsen, chairperson and founder and guiding spirit of the entire Poetry Day organization, steps up onto the stage. A pretty, smiling red-head of some forty summers, she wears an elegantly flowered gown and looks happy. She is, in fact, an actress by profession which perhaps explains that she can smile so blithely in this damp hall. Or perhaps it is her pleasure at delivering the accolades and the prizes. (By tomorrow morning we will all be kicking ourselves because in the furor and the damp no one had the presence of mind to jump up on the stage and say Hip Hip Hurrah for Lene herself! But next year we will make that up to her.)

The prizes consist of a bronze statuette sculpted by Peter Lunding — it represents a naked figure fighting its way through grass — and cash. First there is an honorary prize, a bronze “Grass Prize” statuette awarded to Grethe Kofoed of artcome.dk for her extraordinary, unremunerated engagement in establishing and maintaining the Poetry Day website, for her work on the posters, brochures, and maps over the past three years. All the others who have helped so much, of whom there are many, are also thanked with shouting applause and foot stomping

Next comes three further categories of the so-called Grass Prize — a statuette and twelve hundred dollars to each of three persons, all donated by the sponsors. The first, for poetic achievement, goes to the very distinguished Danish poet Erik Stinus, nominated by the poet Marianne Larsen, decided by vote of the Board of Directors. Next comes the Popular Award, Those who were in the Garden today listening to the poets read were urged to cast a vote for which of the readers they liked best. It turns out that only half as many people showed up to listen this year as last — but still, an audience of 2,000 on such a waterlogged day is considerable. Of those 2,000, precisely 475 have cast their vote for Jacob Hallgren and another 475 have cast their vote for Jonas Gülstorff. The two are called up to the stage to fight over the statuette and share the cash. Jonas Gülstorff goes one step further and shares his share of the cash with those performers who he shared his patch of grass with today: the tapdancer, Michael Sandwick, bassplayer Andreas Bennetsen, and dressed in tux and ruffled white shirt, playwright Lennox Raphael (whose 1968 hit underground play Ché! many will recall).

Finally comes what is called “The Poetry Day Random Prize.” For this the names of all 100 poets who have read today are thrown into an urn, and the two lawyer-poets who sit on the board are invited up, one to hold the urn, the other to pick a name. The lawyers, presumably, lend an air of legality to it all. Into the urn goes a hand and out comes a little green slip of paper. A name is read out: Thomas E. Kennedy. In other words, me! I am invited to come up to the stage to receive my prize.

Lene Poulsen, Poetry Day Founder and Chair, and Henrik Nebelong present "Random Grass Prize Award" to Thomas E. Kennedy, who did nothing to deserve it (photo Gorm Valentin)

I don't know how long it takes me to walk from my seat to the stage, but it seems rather lengthy, and all the while my yin and yang are duking it out: Take the money, put it in your pocket. Don't take that money. Someone will come after you. There will be allegations of corruption. You're an insider. Take it, you won it fair and square. Don't take it. You'll give the whole proceedings a bad name…

By this time I am on the stage and the chairperson is saying how happy she is that I have won this prize because both Alice and I have been part of all this from the beginning, and she recalls how it rained just as hard the first time, five years before, and all the while she is saying these lovely things, I am thinking: Give the money away to a worthy cause. But to which cause? To some writers' cause. And then it comes to me. Of course! PEN. I think of PEN because I know that they fight for the right of free expression and that they help writers who wind up in prison because of things they have written, and they help the families of these writers as well.

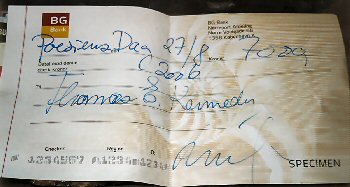

The chairperson, smiling her dazzling smile, hands me the bronze statuette — the Grass Prize. It actually looks like someone imprisoned — how fitting. She hands the microphone to me, as she is about to make out one of those giant “specimen checks” with my name and the amount and the date, and I say, “Please make it out to PEN. To the Danish chapter of PEN.”

One of the worst things in the world I can imagine is winding up in prison for something I wrote — or to fear writing something because I might wind up in prison.

The chairperson, smiling her dazzling smile, hands me the bronze statuette — the Grass Prize. It actually looks like someone imprisoned — how fitting. She hands the microphone to me, as she is about to make out one of those giant “specimen checks” with my name and the amount and the date, and I say, “Please make it out to PEN. To the Danish chapter of PEN.”

Grass Prize statuette

Giant "specimen" check for 7000 Danish crowns -- about US $1,200

“PEN, please. Make it to PEN.”

“Now,” she says, “This is the second time that this prize has been donated to PEN. Please tell us why you are making this generous gesture.”

I did not expect this, am not prepared, anticipated nothing but a polite smattering of applause. “Freedom of expression,” I say, struggling to compose some coherent statement, but at the moment I cannot even remember what the letters “PEN” stand for [they stand for Poets, Playwrights, Essayists, Editors, and Novelists], so I just say, “PEN stands for freedom of expression, and that is important.” I completely forget to mention the writers in prison program which is where I want the money to be directed. Meanwhile the chairperson is writing my name in huge felt-tip script across the face of the check. She kissed my check and released me with the enormous specimen check.

People are clapping as I come down the steps to the audience, but the first person I look at glowers and says, “PEN is a corrupt organization.”

And I remember the controversy. How could I have forgotten? The Mohammed drawings. The furor. The flag burnings. The embassy burnings. The diplomatic clumsiness on both sides. And the attack upon the editor of a rather right-wing newspaper who had printed those Mohammed drawings to see what it might provoke and the proposal by a faction in PEN Denmark that the editor in question should receive an award for his support of freedom of expression. Fortunately he did NOT receive the award, only some words. And fortunately, I did write a letter to PEN saying that I thought it was only fair that his right to free expression, like that of all others, should be supported, but that he absolutely should not receive any prize supported by my dues.

I tell this to the fellow who is looking skeptically at me, and he seems relieved. “That was a good thing you did that.”

Others are clapping me on the back and congratulating me. I begin to suspect that most of the people present do not know why I received this prize. It was mere chance, a drawing amongst the names of the 115 poets who read today, but people seem to think I have done something wonderful which is being recognized with this prize. I almost begin to think that I did receive the prize because of something wonderful I did, but I just can't remember what it was. Perhaps I really am wonderful, but in truth, I know that I only gave away the money for fear of being suspected of corruption and that I only received the prize because of a quirk of fate in a drawing of names, yet I continue to clutch the little bronze statuette as though I deserve it. I even begin to plan how to phrase it on my CV. I have done nothing wonderful. I am a despicable person. I only came here to have fun, and now I got a prize for that.

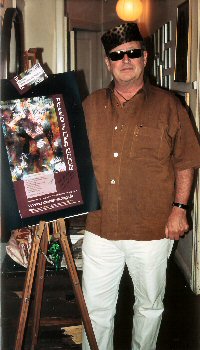

I stand near the bar in my leopardskin pillbox hat, trying to explain to anyone who will listen that I have done nothing wonderful, but people keep beaming at me, murmuring, Wonderful! Terrific! Good work! Nice move! Bob and Lisa and Alice and I clank bottlenecks. How I wish that prize had gone to Bob. He could have taken the money and run back to Kansas City — a partial refund on his travel expenses. He could have put the brass statuette of the Grass Prize in the New Letters office on Rockhill Road and said to people, “See that? It's a Grass Prize from Copenhagen Poetry Day. I was there.”

A previous winner of this Random Prize comes over to explain earnestly to me that he too used the money for a good cause in Africa, and I want to explain to him that I did not really use it for a good cause. I did use it for a good cause, but all I really wanted to do was clear my name.

Trying to echo the presumably mock-cynical tone, I say, “Well, you know, as Bernadette Devlin said, 'When I sell my soul, the price will not be measured in small bills.' Now if it had been twelve thousand dollars…”

Then an American guy I have never seen before and who looks like a young Dennis Hopper is there smoking a joint and telling me, “You know there were two Africans sitting beside me in the audience when you gave your prize to PEN. They didn't understand Danish so well and they asked me disbelievingly, 'Did dat guy jus' give away all dat money!?' And when I said yes, they just walked out in disgust.” But his own reaction, he explained, was that when he saw me there with my tortoise-shell eyeglasses and my leopardskin pillbox hat he figured me for a New York Jew. “But then I started thinking, Hey a guy who gives twelve hundred bucks away is a guy I want to know. He must not need it. He must have plenty more…”

The author in leopardskin pillbox hat with Poetry Day (Poesiens Dag) 2006 poster

He snuffles into his joint and wanders away.

The day is reaching its end, and as I stand there wondering whether the American guy was really anti-semitic and whether I should be annoyed, I see him quietly gathering up all the heaps of left-over food and wrapping it carefully in delicatessan paper in order to transport it over to a homeless shelter. “I play a lot of places where there's food left over,” he says. “There are people who can use it.”

I nod. “You're carrying on like a New York Jew yourself, buddy.”

“Well,” he says, “At least the Muslims won't burn your flag for saying that!”

What remained of the 115 wet Poetry Day poets at 5 p.m.

(Photo: Gorm Valentin)

[copyright 2006, Thomas E. Kennedy]