| an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins |

|

I KISS YOUR FEET:

A VISIT TO BARONESS VARVARA

by Thomas E. Kennedy

”There's no use storing memories in your brain. There no one can read them!”

-Varvara Hasselbalch

”There must always remain some secrets in a woman's life.”

-Varvara Hasselbalch

Varvara Hasselbalch lives in a thirteen-room patrician apartment on one of Copenhagen's broadest and greenest boulevards, overlooking an “impressionist's garden” of last-century bronze sculpture – a naked boy bearing a vessel of wine, a voluptuous reclining nude, on a background of castle moats, weeping willows, linden trees, neatly trimmed softly sloping grass plains. Varvara is 83 years old, one of the last Danish aristocrats, a baroness from her third marriage, a direct descendant of the Russian Princess Varvara Gagarin, whose line dates back to the ninth century.

Varvara in her library, seated in chair designed by Princess Varvara Gagarin 150 years ago

Through the massive oak double- portal we enter her building, agreeing as we climb the stairs to the second floor that we mustn't exhaust the woman; how could we know that five hours later we would be descending the stairway again, more exhausted than our hostess who opened to us a glimpse of the great story and the history that is her life.

Author of five books with two more in progress, Varvara has lived a life of many facets. Professional photographer, writer, traveller, highly-decorated ambulance driver during World War II, Red Cross relief driver delivering supplies to the prisoner-of-war camp inmates of German-occupied France, award-winning equestrian . . .

Varvara's decorations: from left Légion d'Honneur, Croix de Guerre with two bronze stars

”I was always being decorated by tiny men,” she says. ”It was a problem.” She stands easily six feet tall and would see them coming and wonder what to do when they proferred the kiss of honor. ”Bend down so my bottom was sticking up in the air?” Finally, she learned a technique of dipping at the knees which preserved both her dignity and the royal pride.

Now she greets us at the door with a broad smile and laughing brown eyes behind large spectacles, wearing a yellow tee shirt and red slacks, leaning on her rollator. A long angry scab marks the back of her right forearm.

”I fell off my bicycle,” she explains. ”I was out shopping and stopped to buy two dozen oysters. It threw the weight of the bike off and I fell. Some kind strangers helped me up, and I had to kind of rattle all my bones to see if any were broken. None were, but the real indignity was when I got home I found there were only eleven oysters in the basket!” She laughs – a melodious, self-ironic laughter which is almost a giggle but too musical and dignified to be called that.

Having learned that she rides her bicycle amidst heavy traffic – on Great King Street and Broad Street, I ask hesitantly, ”Don't you have a three-wheeler?”

”Oh yes but it's much too difficult to balance.”

The foyer is crammed with a variety of objects: a counter-like display behind which stands a mannequin dressed as a housemaid, a stuffed deer that seems to be peering out from behind a display of colored glasses, a dozen or more books, face out, a sign that says, Any idiot can keep things orderly; it takes genius to master chaos; another lying on a table says, In case of fire turn this sign. I turn it to the obverse which says, In case of fire you idiot!

Varvara chuckles and guides us into her library where snacks and champagne are waiting. We sit in chairs designed some 150 years before by Princess Varvara Gagarin and with silver forks spear tidbits of smoked oysters, pickled salmon and pâté de fois gras from sardine-tin-shaped porcelain bowls richly decorated with gold plait. The plaiting on one is cracked. ”I put it in the microwave,” Varvara explains with a laugh. ”It couldn't stand the heat.”

This room has the soul of a poet's, I think as I gaze around, a living museum. It makes me think of Pablo Neruda's Isla Negra home which I visited five years before, chock full of any and every manner of thing that captured his delight during his lifetime. On a shelf above where Varvara sits is an LP-sized 65 million-year-old ammonite snail fossil. “Did you know by the way,” she says, “that only one in a million snailshells – the ordinary edible snails – coil anti-clockwise. Very rare. I had a pair as ear rings once. Whenever I mention that to people eating snails, they go mad examining the shells on their plates!”

There are delicate ivory carvings, an antique porcelain hashish chillum, an 1850 British cockfighting chair, to be straddled like a horse with secret drawers to store one's winnings. Atop the back of the chair is a kind of platform on which to rest one's forearms while the cocks do battle; there Varvara has placed an official-looking book entitled, Known Danish Alcoholics: Published in Cooperation Between the Sociological Observation Clinic and the Danish Alcoholics Association. Naturally I cannot resist opening it – to find inside nothing but a mirror. She laughs happily. ”I once showed that to a woman who became livid. I had no idea she was really an alchoholic.”

Mounted head of deer hunted by Varvara, crowned with rhinestone tiara |

There is an exquisitely cast gold cigarette box that had been her great-grandfather's a century and a half before – she suggests I pick it up and admire the work. “You can't find a seam or a hinge or a joint on it,” and adds, “That's the sort of thing I pack away if I expect questionable visitors." There are a South American fingernail file made from the tongue of a fish, a fox-hunting bugle (”To call the guests in to dinner,” Varvara explains.), a glass containing the 12-ringed tail of a rattler she shot on the Bernard Baruch estate in South Carolina. On one wall are the mounted heads of two animals she hunted – a fox and a deer, sporting a rhinestone tiara; |

|

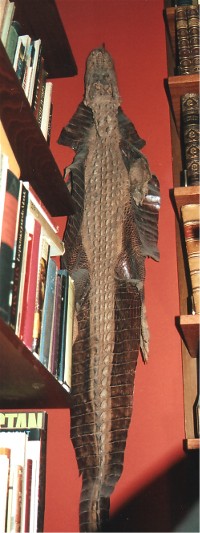

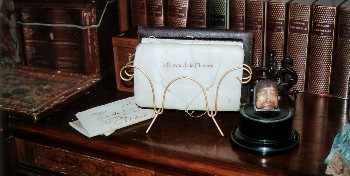

on another, between two ten-foot shelves of leather-bound gold-embossed antique books, the hide of an alligator she shot in South Carolina. On the table before me in a glass case are her Croix de Guerre with two bronze stars, Légion d'Honneur, and Italian diplomatic decoration. A letter on powder-blue writing paper is folded alongside the case. Indiscreetly I fold it open – an invitation dated a month before from King Michael of Romania for Varvara to attend a surprise party for his Queen. Too polite to raise an eyebrow at my indiscretion, she confesses,”I'm proud of that invitation. Unfortunately I had to decline.” To my left is a large, painted, equestrian Frederick-the-Great table clock; alongside it an array of small non-functional brass clocks from Afghanistan, frozen at odd hours – 12:11, 6:17, 9:43... ”They contain kohl,” she explains, a fine powder of native stibnite or antimony, used in the East to shade the eyes. |

Crocodile shot by Varvara in South Carolina |

“An order of Italian monks who are forbidden to possess clocks or watches wear those skulls on their rope belts in the cloisters, with the clocks concealed in the skulls. They mustn't read the clock without thinking of the fact they have to die.” She sips her champagne. ”Personally I find it exciting to speculate about what will finally kill me. I told my doctor that the other day, and he said not to worry, all his patients live to be 101. Oh, I said, that's too boring, and he said, 'Ah but I must keep you alive, I can't afford to lose you.'”

|

Her merry, almost child-like laughter contrasts agreeably with the deep vigorous baritone of her voice whether she is speaking Danish or English. She also speaks French, German Swedish and Portuguese, and her blood is a mix of Russian, Danish, German, and Swedish. “Do you think of yourself primarily as a Dane or as a European?” I ask. “Well, a Dane is a European, isn't that so? I'm absolutely a Dane. I've always waved the Danish flag wherever I was. Even when I |

Oil portrait of Princess Varvara Gagarin |

Varvara was 19 years old when she enlisted in the SSA, driven from the beautiful seaside of Le Touquet by an unhappy romance, an experience she describes in her book, Private Varvara 5272, published in 1944 after her return to Denmark when the Germans were still occupying the country. In the book, she describes among other things the bombing by the Germans of a French hospital. This detail particularly annoyed the German Gestapo in Denmark who visited her in her Copenhagen mansion. Fearful she would be interned in a death camp, she received the little Gestapo functionary from behind an enormous Louis XVI desk “to make him feel even smaller than he was,” and dismissed the quisling Danish translator who had accompanied the Nazi – a decision made on the basis of disgust for the turncoat but also for strategic reasons. If she was interviewed in German, she would have an excuse to take more time formulating her responses since her German was slower than her Danish.

She was working as a photographer at the time and had arranged with her dark-room assistant, working on one of the upper floors of the mansion, to telephone every few minutes to underscore for the Gestapo man that it would be noticed if she were to disappear.

The Gestapo functionary asked why she had claimed that the Germans bombed a hospital in Bar Le Duc in 1941. She asked the man if he had been in France at the time, and he named a city neighboring Bar le Duc where he was stationed. “But then you were there!” she exclaimed. “You saw it yourself! You were right there! Don't tell me you missed that!”

She feared she may have gone too far, but the little man became flustered, gathered himself and left her with a warning that her book would have to be removed from the bookshops. When the Gestapo order came through to ban the book, they were told only two copies remained. These were handed over without mention of the remaining two thousand in stock which were then sold under the counter to those who came in requesting Varvara's cookbook. When she received an accounting from her publisher of the distribution of the copies, it included a notation that read, “Two copies to the Gestapo.”

Varvara's mother's life, ever since the untimely death of her husband not many years after Varvara was born, had been ardently dedicated to horses and men. Her mother forced Varvara to become an equestrian herself and to compete in jumping competitions throughout Europe from a tender age. “If I didn't take first prize in the competitions I caught hell from her. Unless we were in the same competition. Then if I took first prize and she took second, I caught hell for taking first prize from her. But if she took first and I took second, I caught hell for not taking first.”

Both Varvara and her mother served as para-medicals during wartime, Varvara as an ambulance-driver in World War II in a combat zone, her mother as a nurse in a military hospital in neutral Denmark in World War I. Her mother's career, however, was cut short, so to speak, when she attended the amputation of a wounded soldier's finger and afterwards tossed the finger to a hungry dog who evoked her sympathy.

“I get the definite impression you are a pacifist,” I say.

She looks horrified – or perhaps she did not hear what I said. “A what?!”

“That you are against war.”

“Well, of course, I am. It is ridiculous that people keep wanting to kill each other and fight instead of enjoying this beautiful life. But of course they have been doing that forever. That's what they do.”

We have finished our hors d'oeuvres now, and I long for one of my little cigars, a petit Nobel, the cigar maker whose estate funded the excellent Hirschprung Collection here in Copenhagen, not far from where we sit. People who are sensitive to smoke tend not to like the smell of the various tobaccos – my current batch being Brazilian. I ask if she would mind.

“Only if you don't mind,” she says and takes a cigar of her own from a fur-covered cannister alongside her and lights up. Then I recall that one of the signs in her entryway actually said, Thank you for smoking!

She observes me as she smokes her little stogey. “You don't intend to publish this interview in the tabloids, do you?”

“Certainly not. And wherever it's published, you will have the final decision over what stays in and what does not.”

“I have been enjoying your essay about Søren Kierkegaard and Regine Olesen in The Literary Review,” she says, “and your novels as well. But I must say, I don't care for all that fucking stuff. In Kerrigan's Copenhagen, you used the word 'fuck' 27 times and in Bluett's Blue Hours 29 times. Might be time to find a synonym.” Her smile is sphinx-like.

Alice has told me that while reading my novel, Kerrigan's Copenhagen, A Love Story (Wynkin de Worde, Galway, Ireland, 2002), Varvara phoned her to remark about the vulgarity when she came to the chapter in which the main character, Kerrigan, goes into a pissoir bedecked with mirrors where the patrons can view their own members; Kerrigan is startled to see his own “little mouse” peeking up at him.

“Alice,” Varvara says, gesturing. “Are you nimble enough to climb up on that chair and take down that long white object in front of that ammonite snail fossil for me?” Alice does as requested, and Varvara hands the object to me. “Can you guess what that is?” she asks.

It resembles a sun-bleached thigh bone of some sort, about a foot and a half in length and an inch or two in circumference. Then I spy the head, the single eye. I hesitate, but plunge on. “Is this the penis of a whale?”

Varvara with whale appendage |

“It's a whale's prick!” She bellows with merry laughter. “This would give any man an inferiority complex,” I say. “It's certainly more than the little mouse you describe in Kerrigan!” To Alice again she says, “Look on that wrought iron stand over there. You'll find the elk's prick. There, the one with the little feathery head on the end.” It's as long as the whale's but a third the circumference. Varvara's laughter resonates through the room. She has a way of looking into one's eyes when she laughs, sharing the pleasure of her humor directly and openly through the light in her warm brown gaze. |

We fall silent then, nursing the last of our wine, and I find myself contemplating the extent and quality of the life she has lived in a mere 24 years more than my own – her laughter at the air raid shelters in the basement of the Ritz Hotel in Paris, complete with liveried footmen doling out distilled water to aristocrats in high-fashion air-raid outfits from Molyneux, reclining in chaise lounges; tending the wounded in Bar le Duc amidst the reek of gangrene, blood and sweat in hospitals full to bursting, her hands and uniform and the stretchers drenched in blood; being roused from sleep after five minutes by the air raid sirens; the ceremony she attended in which the Croix de Guerre was awarded to a man near dead of gangrene infection and her admiration of the officer who bowed down through the awful reek of the man's dying to deliver the kiss of honor. The trains kept coming, one after the other, packed with the wounded and the dying – French, Italian, British, American, north African, German, the shell-shocked gone mad, and German bombers appearing out of gloriously sunny skies, and the Brits at the Hotel de Metz taking their five o'clock tea from teapots full of whiskey; a Senagalese-French soldier with a nosebag full of dried out enemy ears he was gathering for his fiancé – cut off with his coupe-coupe knife, hanging to this day on the wall beneath the mounted head of the deer she hunted; her colleagues with dark circles beneath their dazed eyes as they were dive-bombed and straffed while people in Rolls Royces and Cadillacs, one to a car, fled along the roads.

When she was awarded the Croix de Guerre at the age of twenty, it was with the section that had driven over 50,000 kilometers and helped transport 14,500 wounded under difficult and dangerous conditions, under fire from German artillery and bombs at Bar-le-Duc and Beaune. And when she was finished there, after the German occupation of France closed down the SSA, she returned to Paris and was enlisted by the Red Cross to drive a five-ton Matford truck through occupied territory to deliver supplies to the nearly two million French POW's in hundreds of POW camps, playing diplomat to the Germans in order to be allowed to deliver tons of bread, underwear, socks, sleeping bags, gloves, scarves, pull-overs, shoes, shirts, biscuits, while trying to procure information on conditions in the camps without enraging the volatile German commandants or endangering the prisoners.

And later, back in occupied Denmark where she began her career as a portrait photographer, she took pictures of secret documents on microfilm for the Danish underground and smuggled them into Sweden. Then, in fear, she went underground, disguised herself as a man, but forgot how she was dressed and called by nature once went into a public toilet – a woman's toilet – and was thrown out by the attendant.

Her book ends with a call to end war: “Soldiers have to learn to practise peace.”

It occurs to me then, some four years earlier at a book fair, not yet really knowing who Varvara was, that I had attended a launch of her book Varvara's World (Aschehoug, Copenhagen, 1997), mostly about her life among the European aristocracy. I was in the audience at a public interview of her conducted by the editor of a magazine which is roughly the Danish equivalent of People. With enthusiasm, he asked her, “You have actually been in company with nobility, with kings and queens, princes, and princesses: What are they really like?”

“Oh, pretty much like you and me,” she said. “Only not quite as snobbish.”

She leads us further through her thirteen rooms, shows her collection of handcuffs hung on the wall above one of her ten-foot bookcases. “They are up there where they can't be reached because I don't have the keys anymore and don't want people playing with them. When I was to be married, a 2éme bureau friend – you know, that is the French equivalent of the CIA – cuffed us together, and we didn't have the key!”

Everywhere are objects of elegance, charm or humor. She has a fascination with gadgets – a battery-operated hand in the palm of which one can place a drink to be run down the table to someone else, stopping automatically if it comes to an edge. She laughs happily when we cry out, expecting it to crash to the floor. On another table are a collection of expensive ceramic shellfish – only the lobster has a special feature; she presses a button and it begins to writhe and sing, “Don't Worry, Be Happy!” Again, her child-like laughter, and it suddenly registers on my vision that in the center of the room is a low table set with an oval of tiny doll-house chairs, as though set up for Alice-in-Wonderland's Madhatter's tea party – in many of them are seated figurines, tiny animals mostly.

We ask about that side of her humor and somehow are led to an account of the TV team that came in not too long before to film a full-length prime-time program about her and her apartment. She greeted them at the door, an entire crew with tons of equipment, and Varvara had dressed herself with an enormous bandage on her head and an old smock, hobbling on crutches. The director of the program looked aghast. “But we have to get ready for filming!” he yelped. She still laughs at the thought of it. “It was just a joke,” she says. “The bandage came off just like that, and I had on fine clothes beneath the smock!”

There is a collection of mini-cigar boxes, silvered roses, the silvered casts of first shoes of the family's babes, a torreador's hat and picador spears (presents from the toreadors, as Varvara was a bullfight afficionado in Portugal and Spain), a waste-basket trimmed in genuine leopard skin, a small bronze squirrel.

Squirrels were her mother's favorite animal after horses. She carried a small ivory squirrel that had belonged to Princess Gagarin in her handbag, and in fact – instigated by a Danish prince who wanted to test the skills of a celebrated British tattoo artist – had a squirrel the size of a saucer tattooed on her thigh. A French scandal sheet in the 1930s reported that the animal's beady little eyes were focused in a naughty direction. And young swains bragged to one another that they had seen the squirrel in person.

“Gagarin?” I ask. “Are you in family with the Russian astronaut, Gagarin?”

“Actually he bears the name because one of his ancestors was a loyal servant to my great grandmother's family – in Russia, a loyal servant was granted the right to bear the family name of their masters.” She stubs out her cigar in an electronic ashtray that coughs – she laughs merrily at the sound.

Like the Danish scandal-magazine editor, I cannot help but wonder what it is like to attend royal parties and receptions.

“Dreary,” she says. “They have to take the hands of hundreds, thousands of people they don't know – and really don't care about and who don't really care about them. Prince Axel of Denmark used to go around at receptions murmuring to everyone whose hand he clasped, 'I've just murdered my mother-in-law; I've just murdered my mother-in-law,' and he swore no one even noticed.”

Now we have finished with the library where we started and proceed to the sitting room, the largest single space in the apartment. There are two great sofas, each adorned with a half-score of elegant-looking pillows decorated opulently with colorful elephant portraits. “I bought those for ten crowns apiece in Netto,” she says. (Ten crowns are not quite a dollar and a half, and Netto is a cut-rate Danish supermarket.) “That's where I buy my smoked-oysters as well.” On the wall above is a massive gilt-framed, 18th-century oil painting of Josef II of Austria, brother of Marie Antoinette. Across the room by a tall sweep of windows hangs an enormous canopied garden swing of Indian teak flanked by portraits by Winterhalter (1805-73) of the lovely faces of Princess Varvara and her sister as young women. Winterhalter was German, a painter of the Russian court and Queen Victoria's preferred portraitist. Behind the garden swing are three very large colored bottles, some five and a half feet tall. “Those were hand-blown in Portugal. I asked the glass-blower to make one as tall as myself, but he said he didn't have enough breath for that!”

|

To one side of the garden swing is a 19th-century British smoking chair – the leather seat is saddle-like and mounted like a horse, so the smoker can lean forward on the chairback which contains an array of drawers for smoking paraphernalia.

On one table sits a lamp made from a very large salt lump hundreds of thousands of years old from a German mine; atop the salt is perched a rare caricature of a sitting giraffe. “That's because they used to call me the giraffe in school – I was so tall,” she explains. The next room, facing cattycorner down to the green willows, is Varvara's bedroom. One corner is occupied by an enormous canopied bed that closes like a bedouin tent. Either side of the top is decorated by a yard-long renaissance angel, and on the floor to either side, imported from Portugal, is a life-sized painted |

One of two painted brass lackies flanking Varvara's bed |

Varvara's sculpture of Afghan warrior woman |

brass lackey on a pedestal holding aloft a multi-colored feather-duster. The one on the right sports a “smile” sticker. Varvara tells us how she fell getting out of bed not long ago and instinctively grabbed for the one lackey for support, toppling him. “Thank God he didn't fall on me. He weighs a ton! I would be gone. That would be ironic!” Behind me, as I turn, I am startled to see, seated in the corner, a robed Afghan woman, her face veiled, a bandolier of 30-millimeter bullets crossing her breast, her feet decked in supermarket slippers that glow in the dark – another mannequin which Varvara has dressed up . |

“I only recently rediscovered that,” says Varvara. “For years it was lost among the umbrellas.”

Between the balcony and a window is a triptych bookcase. “I bought them in Ikea for a pittance,” she says. “Aren't they wonderful?” And indeed they fit into the otherwise antiquely furnished room without a seam. The shelves are crammed with books about early 19th-century Russia, the research sources for one of the books she has in progress, based on the love letters – 20 thousand handwritten pages – exchanged between her great-grandmother, Princess Varvara of St. Petersburg, and great-grandfather, the Danish diplomat Baron Otto de Plessen. There are several cabinets filled with their letters. “Thankfully,” she says, “They corresponded in French, not in Russian, or I wouldn't be able to read the letters at all!” I ask if she has a title for the book, and she smiles at me. It takes a moment before she answers. “Yes. I Kiss Your Feet.” Varvara laughs. “It is taken from the letters. The complimentary close. I thought, Oh! Don't you get any higher than that! There was no sex, but that's what he said, how he closed the letters, and he asked her not to wash them!” Varvara shudders merrily. “Oooo! I thought of giving it a formal title – My Great-Grandparents, the Princess and the Baron, etc – but it needs some humor. It was they who decided that the family needed new blood in their veins, so when their son Joseph (Baron Joseph de Plessen, 1860-1912) – he was the one who had the Copenhagen mansion built – reached his maturity, they found, a Swede for him – Sophie Louise von Eckermann who lived outside Stockholm. They presented Joseph to her, saying, 'This is the man you will be marrying.' Think of the poor girl. My grandmother.”

It is clear from the expression on Varvara's face, in her dark brown eyes, her smiling, appalled mouth, that she finds herself close to the mystery of humanity, of human history, the history of her own family. She has a vantage point of age, of experience, where amazement, amusement, affection and repulsion can all occupy the same space of consciousness simultaneously. “Unfortunately, there is a gap in the letters. They would have been the juiciest ones.”

“Today,” I suggest, “there is a genre called creative nonfiction. Why not imagine what happened in that gap?”

She gazes musingly at me. “Yes,” she says. “I will have to use my imagination. But I will also have to requisition the missing letters from the royal archives.”

Our eyes meet – her dark brown experienced gaze upon my blue fiction-making one – and I wish I could enter her mind just then, I wish I could compare our thoughts, our speculations about ourselves and one another. Does she see before her a charlatan who invents from today that which cannot be known of yesterday? Do I see a woman so wedded to fact that she will not venture beyond it? Do I see, in the momentary lapse of humor of her brown eyes, cool appraisal? Or a mirror of my own image of myself? Is her world one of action and objects opposed to my world of the imagination? Is it a moment where we cannot meet, or simply choose not to?

Alongside the Russian books is a balcony, glass doors open to admit the air of the cool September afternoon, a view out to the weeping willows and sun-streaked grass, and alongside that a Japanese chest upon which lies a reclining Buddha. “They say a lying Buddha brings good luck,” she says.

Antique passports – left, of the Baron von Plessen (Varvara's grandfather), right carved bone Liberian tribal ”passport”

Then there is a steamer trunk, and on a chest of drawers behind it the 19th-century passports and letters of transit of the Baron and his wife. It takes several moments to untie and unfold them and read all the official inscriptions and pronouncements by the “King of Denmark and of the Vandals and the Goths.” Just beside them is a Liberian “passport” – a painted, carved bone face about the size of a yo-yo, used to show by members of one tribe travelling through the territory of another where they are from.

|

On the wall above is a large oil painting by an unknown artist dated 1689; it depicts a young Dutch girl with a light, round, charming face, holding a 'Fallsun' hat – (“I don't know how that word is spelled,” Varvara says) – one designed to protect a child's head in case she should fall. Beneath the Dutch painting is a marvellously ornate gilt frame; looking closer, I see there is no picture in it – it frames the Aubusson tapestry curtains. “The frame is a work of art in itself,” Varvara says. I begin to realize as we enter the next room, a dining room currently in use as her study, that it is impossible, utterly impossible, to report all the great variety of things here. Beside the doorframe is a tall glass case of antique samovars, which reminds |

17th-century Dutch oil painting; below, framed Aubusson tapestry curtains |

There, under a canopy suspended from the center of the ceiling, Varvara serves refreshments: Neuman bittersweet chocolates offered directly from the box and shot-glasses of north Jutland aquavite. Within the canopy are all sorts of artificial stuffed birds on perches – but, wait! They are singing! Varvara watches us, a mischievous glint in her eye, her hand on a button beneath the table which produces the bird song. While I study the living fish in a large aquarium to one side of the room, she rummages in the refrigerator for fresh batteries and film for my Nikon which has gone dead. On the refrigerator door is a picture of a skeleton with an English caption: I Miss Your Cooking. And another sign in Danish, Since You Have So Little Time Left, Get Busy!

Varvara in her kitchen

I close my notebook, put away my camera. The life here is too enormous to capture in a few pages, a few photographs. Alice and I are exhausted. Varvara looks tired but raring to continue as she pours a third snaps for each of us, herself included. We have our jackets on now. Varvara glances at us with a smile that seems at once pleasant and sad. “I can see you are on your way.”

“Please don't get up,” Alice says, but Varvara doesn't even entertain the possibility of not following us to the door. She is three quarters of our ages combined and has twice the force. We walk through her photography studio, the ceiling studded with spotlights, the one wall adorned with a folding rack of black and white portraits of faces from Danish society and nobility of decades past, the other with folding poster-sized colored portraits she has done of Africans in full regalia. Varvara has had a long and distinguished career as an international portrait photographer. Down the long hall, she gestures. “There's the dark room,” she says with a smile. “But it's dark.”

At the door she and Alice kiss. I am allowed to embrace her lightly, wishing I could pull her close to me, wishing to hold that force of life and passion and humor and history and experience and, yes, humility, close to my body for just a moment.

My Devil-May-Care Mother (Min Fandenivolske Mor), Varvara Hasselbalch. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1993 (in Danish) ISBN 87-00-13332-9. 186 pp. (also available on tape).

Private 5272 (Menig 5272), Varvara Hasselbalch. Copenhagen: Hasselbalchs Forlag, 1944. (in Danish – also available unpublished in English).

Madeira (photographs), Varvara Hasselbalch. Copenhagen: Endes & Calendes, 1955.

A Nobel House for Doctors (Fra Adel til Lægestanden), Alice Maud Guldbrandsen. Copenhagen: Lægeforeningens Forlag, 1995 (in Danish – English summary available). 64 pp (copiously illustrated).

[copyright 2003, Thomas E. Kennedy]