NOT FOR GIRLS

Alice Maud Guldbrandsen

Thank heaven for little girls.

For reasons that have nothing to do with this story, the marriage was not destined to last. But fortunately, before my divorce in 1972, I managed to complete an education as a bilingual correspondent in English and Danish. In order to manage my work in the family business as well as being available for husband and children, I did that via evening classes. The reading and written assignments I had were done at night, while the family slept. Because, as my sweet mother-in-law said, “That's nothing for a young married woman and mother of three to waste time on!”

ALICE MAUD GULDBRANDSEN's books include A Noble House for Doctors (Copenhagen: DMA Publishing House, 1995) and Silence Was My Song (Copenhagen: Documentas, 2005), an excerpt from which also appeared in the Danish newspaper, The Berlinger Times, and is forthcoming, in English translation, in The Literary Review. Her latest book is also being translated into English with support from a Danish Cultural Council grant. Alice Guldbrandsen's paintings and photographs have been published in print and on line – inter alia on Web Del Sol and in various books, magazines and newspapers. She has also published articles in a number of Danish newspapers. She has worked as an international secretary, bilingual correspondent, photomodel, technical advisor in a legal department, publicist and press officer.

[copyright 2005, Alice Maud Guldbrandsen]

For little girls get bigger every day.

Those little eyes so helpless and appealing

One day will flash and send you crashing through the ceiling . . ."

-Alan J. Lerner

My mother survived him by two years, and I have an idea that was because she felt she needed the time to put some of the thoughts of her 85 years in order but also to treat her ears to a couple of years of peace and quiet. My father's indefatigable pounding of the keys was a pestilence for her to have to suffer within the four walls of their home, morning, noon, and night. For me, it seemed as natural as the sound of prayer in a church. Hearing and seeing my father write made me feel close to him and secure as well as making me eager to get to work at something myself.

M

y passion for the written word arose in early childhood when I had no job at all, other than as a daughter and a pupil in Miss Marie Kruse's Girls School. The energetic hammering of a typewriter was among the first sounds I ever heard. My father, a journalist, for many years a reporter for the Danish National Times, also worked at home — writing, for unknown reasons, under the pseudonym, “Mr Nobody.” He didn't take his fingers from the keys of his beloved manual until he breathed his last at the age of 83, at which time the family considered burying the machine with him.

My mother's often loud complaints about the eternal clattering made me wonder finally how those two people ever happened to get married. She knew in advance how the man made his living and moreover that writing was his greatest passion. Maybe that was the reason for her discontent. But the marriage lasted for more than fifty years — thanks to my mother's otherwise mild manner and strong will as well as the fact that she was, after all, only a mother and housewife with an out-of-date education behind her. So how could she have managed without him?

I am not quite certain whether my father's writing passion set its mark on my mind, whether it was an hereditary gene or just a coincidence. No matter, I have always loved to write and was unable not to.

All written school work, aside from arithmetic, was a balm for my soul; Danish and other languages were my favorite subjects. And it showed in my grades. That my Danish teacher lavishly praised my compositions didn't hurt either. I'll never forget the A++ he wrote in my essay book with the words, “You should become a journalist or author. Excellent!” I floated home from school that day, and his comment went directly into my “little black box” — the invisible place where I have always preserved my deepest secrets.

But lengthy theoretical lessons bored me to death and got me doodling in the margins of the book or staring out the window while I drifted off into daydreams peopled by creatures, places, persons and events, real and imagined. Too often the teacher would tear me out of those lovely dreams and force me back into grey reality. This showed in my grade book, too: “Alice dreams too much . . .” After school hours I wrote many of my dreams and fantasies down in small copybooks that I hid in my room. Into my blue diary, which had a lock and key, went more personal secrets. For example, only my diary knew that I was secretly reading Agner Mykles's Song of the Red Rubin and D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover. I also confided there that I read these forbidden books by flashlight under the blanket — because that kind of literature was not for girls.

So many things, in fact, were not for girls; my two-year younger brother was allowed so much more. For example, to be a scout. A secret, unfulfilled wish of my own — in my home, that was not for girls either. My father, who had been an avid boy scout, must have harbored a dream of seeing his own childhood mirrored in my little brother. Therefore, brother got the entire bundle of equipment at once: uniform, backpack, sleeping bag, knife, compass, the whole works. Now, my brother was not very large at that time, actually a bit of a shrimp.

It was a big day when the whole family had to follow little brother to the Central Station for the train to his first scout camp — but things didn't happen quite as anticipated. The weight of the heavy pack threw brother off balance so he wound up staggering backwards and falling on his backside — wham! — just two blocks from home. If anyone had seen the expression on my face, they would have had no doubt about my shadowy thoughts: God, what a weakling! I could have managed that much better than him. To make it all even more perfect, the little shrimp was sent home a couple days later with a belly ache and the runs from eating raw corn from the cob. He immediately quit the scouts. I was disgusted how quickly he gave up — when I wasn't even given a chance.

So I established my own scout troop, consisting of half a dozen classmates — all girls who were not allowed to be scouts. We called the club “The Stag Horn,” and organized trips to the nearest woods or park with lunchbags, soda water and blankets, all dressed in dark blue, secret little knives in our pockets. We climbed high up into the trees, unpacked our food and enjoyed the freedom of nature. On one of the first trips we found a little piece of antler from a deer which inspired the club name. The pocket knives were used to carve patterns in the bark of trees, and our parents — blissfully ignorant of the knives and tree-climbing — were pleased that we girls had finally developed a sensible, healthy interest in nature.

Then I got the idea for a club newspaper, and that was my first meeting with the world of publication. I drew an antler for the front page of The Stag Horn and filled columns of news about the experiences of our little corps. I particularly remember a “special edition” issued on the occasion of Hans Christian Andersen's 150th birthday on April 2nd, 1955. To supplement what we already knew about Andersen, we undertook substantial research in the library, bookshops, magazine stands to unearth facts and pictures. We were particularly interested in Andersen's unhappy love for Jenny Lind and other beautiful women. The Stag Horn's special edition was packed with pictures of them and of fairy tale figures as well as a little article in which I had undertaken an analysis of the relationship between the real people in Andersen's life and those from the tales. A true girls' school undertaking! In time, the paper went under, but my appetite for journalism was only whetted.

Like my fellow students, as my high school graduation approached, I gave some thought to a further education. Actually, I knew what I wanted. To be a journalist, like my father. But for the moment, I kept it to myself. I didn't dare risk evoking the words I most feared: that's not for girls. So instead, I firmly informed them of what I absolutely would not do — to work in an office. On the other hand, I was very interested in developing my language skills by taking a job in Paris as an au pair, perhaps combined with some French classes at the Sorbonne. The response was immediate: “No, that's definitely not suitable for a young lady.”

I have never understood that response. My mother, who had been born in 1910, travelled in 1927 to Paris, where she worked as a governess for a large French family for a whole year. When she returned to Denmark at the age of eighteen, she was received in the train station not only by her family, but also by a journalist from a prominent Copenhagen daily. Apparently it was something of a sensation at that time that a young woman had been on her own in a foreign country. The article was illustrated with a large picture of my young, beautiful, beaming mother with a bouquet of flowers on her arm. Her time in Paris made her fluent in French, and for the rest of her life she spoke, in Danish, about how enriching her experiences in France had been. Even now I can recall the exciting stories she told about that time. Perhaps my wish was driven by some little hope for similar experiences, but no. What had changed in the thirty years since? Or were there some unvoiced “memoires misérables” behind the happy tales she told.

“Perhaps I should be a nurse?” I ventured.

“What? A potty swinger!” my father snapped, killing the idea instantly.

A gym teacher? I had been the best gymnast in my school — could I use that for something? But there was one hindrance. I had no problem on the highbar, doing all manner of spring and flip, but I had a morbid fear of diving from the 10-meter board into a swimming pool. I didn't even dare dive from the edge of the pool — a poor qualification for a potential gym teacher.

There was no way around my first choice — to be a journalist. So I told them, decisively. I don't remember the expression on my mother's face, but I could see on my father's that he had expected this. He was too clever to use the not for girls phrase; instead, he spoke about educational expenses. In those days, there was no journalist school in Denmark. Even if I had the good fortune to get an apprenticeship, it would most likely be far away from Copenhagen because at that time you started the four-year education on a small provincial paper. Which would necessitate paying for room and board. There was no such thing as an educational loan then, and an apprentice's wages were minuscule. So my father had to, with regret, inform me that he could not afford to cover the expense. On the other hand, he had good connections in the Copenhagen news world which he promised to make use of. If I could get an apprenticeship in Copenhagen, that would be different — then I could live at home.

I began to hope. But at the same time I remembered how our Swedish cleaning lady, Miss Jönsson, everytime she received her wages, would drop a heavy coin into my little brother's piggybank and say, “This is to go toward the engineer education.” It was not envy I felt, but a strange confusion why this generosity and encouragement was only extended to him and not to me; only later did I realize why: education was not for girls.

My brother did, in fact, become an engineer — but to his credit, he did it all on his own.

My high school exams came, and I passed with flying colors, proudly wore the white graduation cap. I even had a boyfriend who was four years older and a photographer! Before the end of summer vacation, my father had pulled all the strings at his disposal, and one day, beaming, told me he had arranged an interview for me on the major Copenhagen daily newspaper, The Berlinger Times, where a position was vacant. But in the personnel office !

If nothing else, I have always been a well-mannered person, seldom allow my temper loose. But that day, on the spot, I exploded: “I will not work in an office! I told you that! Period!”

My father took the situation calmly. With great conviction, he told me that I should just say yes to that position, get my foot in the door of the newspaper world, and the journalist work would come by itself.

I was skeptical, but what did I know? What if he was right?

Since he had devised the creative strategy, I was not terribly surprised that my father decided to accompany me to the interview. At the main entrance to the newspaper house, he instructed me optimistically, “Now I'll go up first and speak with the personnel director. You wait here until I say so.” It seemed like forever before he was back, his face radiating happiness. “It's all set. You go talk with Mr Ipsen about the rest of it.”

“The rest of it?” I asked suspiciously. “What does that mean?”

“Mr Ipsen just told me there's a big chance for you to get in as a journalist if you just take the job in the personnel office first.” His smile was encouraging. “Just as I said, you only need a foot in the door.”

In Mr Ipsen's office, I was received warmly and offered a seat. I did my best to maintain eye contact and listen. Fifteen minutes later I was out the door, having accepted and signed a contract for a position I with all my heart did not want. Mr Ipsen had made it perfectly clear that if I wanted to be a journalist, this was absolutely not the way. And it was perfectly clear to me that I had been duped by my own father.

Before we were even out the main door, I blew up, hissing out a stream of invective at my overimaginative, overoptimistic and manipulating progenitor, who had pulled the shameless wool over my blue eyes. What was I supposed to do with that clown and with that nothing job in an arch-conservative office full of colorless, ugly, grey-headed old hags — office girls!

On the same street as The Berlinger Times was — and still is — an old serving house known as Bernikows Bodega. I knew very well that the scribbling Mr Nobody needed a stiff drink. So I held up my mask to the end and followed him into the bodega. I only drank soda water at that time and that went down quickly while I studied the honorable clientele — mostly men! For as my father told me, “This is where all the journalists from the paper come to meet and talk.” And I come from a girls school, I thought with a bitter taste in my mouth. So this is not for girls either.

My humor did not improve when my boyfriend, later that day, congratulated me on the job. He thought it was terrific; my father had also convinced him about the fantasy job that lay ahead.

In August 1958 I started as a clerical assistant in that dull office at “Auntie Berlinger” — the paper's nickname among the populace. But I left again a year and a half later to start working in my boyfriend's photography and advertising firm. For having decided that on my own, I earned a loud scolding from my parents, who believed that I had ruined my entire future career. On the other hand, I also received a surprisingly good letter of recommendation as well as a goodbye party. During my time there, in addition to my office duties, I had written two small articles — in the personnel newsletter! One about lost-and-found objects in the office wardrobe and one about a British apprentice's experiences in the various offices of the newspaper during his week's visit. I was invited to write those pieces because, as the dear old office ladies said, “Miss Alice is so good at writing.”

Actually I should have left my boyfriend, too, just because he had congratulated me on getting the job. Maybe then I would have had a chance to try my luck without my father's Utopian guidance and a boyfriend's lack of solidarity.

In retrospect, my disappointment over having been denied an education was so powerful that it all but killed further hopes for anything but love; I married my boyfriend, had three sons and worked in a photography studio with fashion, advertisements, scenography, and as a model — not to mention office work!

Perhaps all this makes it sound as though I was a bitter young lady. Not so. I loved my husband, and my three delightful sons gave my life meaning and fulfillment. I liked a lot of the work I did, too, which was challenging, and I was good at it. And I had nothing against posing for the occasional newspaper advertisement for laundry detergent and Prince cigarettes. But the flame of my wish to write, though nearly extinguished, was still flickering, there was still a glow of hope.

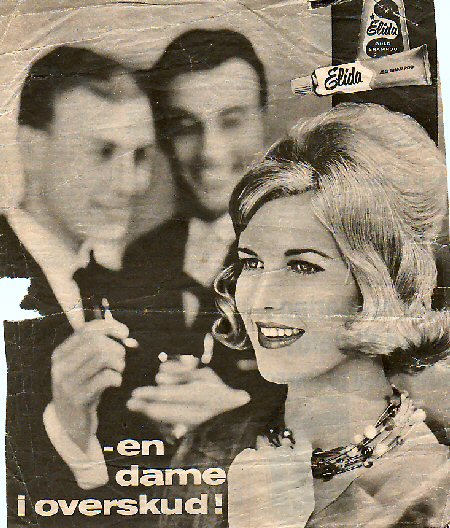

"A lady with a surplus" — 1960s Danish advertisement in which Alice Maud Guldbrandsen demonstrates the exceeding virtues of Elida egg shampoo

In the years that followed, I lived alone with my three boys, and that situation gave me new courage for my life. With the irony of fate, I managed to get a half-time office job and became a secretary in a large organisation where I had use for both writing and speaking English as well as Danish. To my delight, composing brochures, the personnel newsletter and like tasks were also part of the job. I supplemented the half-day post with freelance work for a fashion firm until the organisational position grew to a full-time spot in 1978. During those six years I scratched the writing itch by functioning as a press officer and publicist, which at least gave me a little taste of the beast.

You'd think that those jobs and my family responsibilities would have been enough to fill the day's twenty-four hours, but the spark of my dream to write began to flower again. I looked into the possibilities of applying to the Writers School in Copenhagen, at that time directed by the poet Poul Borum, who was quite prominent in Denmark. I phoned and spoke with him, but he informed me that unfortunately there was no room in the school for a person who had a full-time job. In those days, the school was only for people on the dole, aimed at giving them a further education which would put them back on the job market. Before we finished talking, Borum added, “If you ever do manage to be a writer, you'll have to change your name. There is already a Danish writer with the name Alice Guldbrandsen.” I told him not to worry about that — I had a middle name, Maud. That seemed to amuse him considerably.

Around then, I travelled on vacation in Spain and happened to meet a Danish journalist there. We hit it off, talking almost exclusively about journalism. When I got home again, he contacted me and offered a freelance job writing for the local newspaper where he was employed. I grabbed it, was mostly assigned to film and theater reviews but also to cover some ship launches and similar events. This lasted for a while and could easily balance with my other two jobs, but when I was offered a full-time post on another local newspaper, I had to decline. With three children, I didn't dare let go of my other jobs with all their security. I was 39 years old. Had I said no to a career as a journalist? If so, at least I had done so of my own free will, and when I think of my sons, I never regret it.

In my free time I started writing short stories. The more I wrote, the better I felt. I wrote poems as well and sent some of my work to magazines and contests, but nothing happened. All those manuscripts found their way into a brown cardboard carton marked, Writings. And they're still there.

In the '90s, I learned about a writers workshop run under Copenhagen County's Evening School and signed up. In the course of a year, the workshop opened my mind to the possibilities of weeding and cultivating the inner garden of my imagination. One of my stories evoked considerable enthusiasm in the workshop, and that was encouraging. The workshop leader and I, however, did not quite see eye to eye. He insisted on the necessity of working from an outline — a practice which I found stifling. I also recall him telling one of the writers, who was working on a children's book, “Animals do not talk in real life and should not talk in a book.” Apparently he did not think much of Aesop or George Orwell, Lewis Carroll, Richard Adams, or Kenneth Graham. Nonetheless, I did my best to struggle with some outlines — they all disappeared into the brown carton, never to emerge again.

Some time later, the workshop leader called to say he had selected me to join an “elite” group of writing students. I told him I was eager to join the group. By then I already had a contract for my first book, but when I tried to share that happy news with him, he dropped me. “You're already a writer. You don't need a writers group.” When the book came out in 1995, I sent him a copy; he never responded.

My inspiration for that book came from the place where I worked, an east Copenhagen mansion from the early 20th century. It had been built by a Danish baron for his large and eccentric family of painters, writers, antique book binders, photographers, and hippies, who lived there until 1948 when it was sold to its current owner, the organisation I was working for. The atmosphere of the building fired my imagination from the first day I set foot in it, in 1972. It was as though its walls whispered to me of its history. But neither I, the company management, nor any of the people who worked there knew anything about the mansion. In 1993, my curiosity could no longer be denied and I started researching its past and met the last surviving member of the clan that had lived there, a now 85-year-old baroness, an author herself and a decorated war heroine. Parallel with my day job, my research slowly grew into a book, published as A Noble House for Doctors in 1995.

I wrote in the evenings and on weekends and vacations. It was odd that throughout the day I worked as a secretary in the house whose past history filled the evenings of my imagination. By then my sons had moved out and begun to build their own lives. Having more time for myself to write also reawakened my desire to read, but also to dream. Now, however, I recognized my dreams not as an obstruction to my work — as had been written in my grade books as a pupil in school — but as a kind of research into my own existence.

About a half year before that book was published, my father lay dying. I visited him often and sat and talked with him. Toward the end, the only parts of him that still functioned were his brain and his words. There were only three subjects that concerned him: his joy that his first great-grandchild — my youngest son's child — was about to be born; next, his uncertainty about what awaited him after he died — heaven or hell? The third was my book, which he had read in manuscript as it came to life. He praised the book, and I'll never forget the day he looked at me with his one still-functioning eye and said, “You're a talented girl, Alice. If you had listened to me back then, you could have been a great journalist.”

My father's words are etched in my mind.

Mr Nobody died the day before his first great-grandchild was born and a half year before my book was published. But where did he go after his life was done? My guess is that he went straight down just to have a taste of it, then circled upward again to the top.

It took ten more years — including eight years of office work — before my next book was written. The idea of writing about a violent experience from my childhood, in the last year of World War II, had been working at me since 1988. But I didn't get down to it until 1993, right after I had completed my 47 years of office work. On the other hand there were other jobs in my life: a whole family, three sons, four grandchildren, a wonderful new husband, friends, all of whom deserved my attention and presence in their lives. Other activities also called to me — among other things, my painting; I had been painting and exhibiting on the side since the early 1990s.

It was not easy to let all of that wait another nearly three years while this book absorbed me, almost manically, day and night. Now the book is done, titled Silence Was My Song, published in 2005.

It is a source of wonder and amusement to me that the newspaper which gave the book its greatest attention was my old employer from 1958, The Berlinger Times, where despite my father's best hoodwinking efforts I had never managed to get a foot in the door. In March 2005 — forty-five years after my goodbye party — the Executive Editor of that newspaper telephoned me to tell how much he admired my book, to express interest in publishing one of its chapters as a Sunday feature along with an interview and picture of me, and to ask how I had ever learned to write so well. The week after, The Berlinger Times published a full two-page centerfold spread with a glowing review of my book.

That day I thought about my father and sent him a loving thought: Well, Dad, I never made it as a journalist, but I did become a writer. Not too bad for a girl, huh?

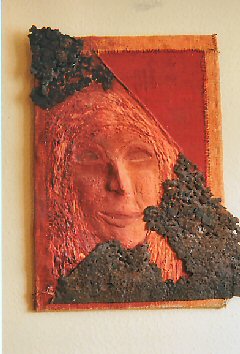

"Liberation" -- self-portrait by Alice Maud Guldbrandsen

(oil, cement, iron)