"Reading has become an active, participant-directed process rather than

passive, author-directed ... the rational-visual act of reading has become an

experience of sight, sounds, and colours."

Paul Kloppenborg

|

|

CONCRETE TO COMPUTER:

The future of visual poetry.

by Paul Kloppenborg

Visual forms- lines, colours, proportions etc -are just as capable of

articulation i.e. of complex combination, as words. But the laws that

govern this sort of articulation are altogether different from the

laws of syntax that govern language. The most radical difference is

that visual forms are not discursive. They do not present their

constituents successively, but simultaneously, so that relations

determining a visual structure are grasped in one act of vision."

-Suzanne Langer, Philosophy in a New Key (1942)

CONCRETE POETRY (Then)

The concrete poetry movement had been started in Europe and Brazil in

the 1950s and 1960s. In the mid-fifties, Eugene Gomringer in

Switzerland and a group of poets working together in Brazil, defined

concrete poetry as writing that "begins by being aware of graphic

space as a structural agent", so that words or letters can be

juxtaposed, not only in relation to each other but also to the page

area as a whole. The Brazilians - Deico Pignatari, Augusto and Haroldo

de Campos-defined "concrete" with an emphasis on the word as a unit

in space.

Traditional verse forms internalise a poem through its language so

that meaning becomes clear when read and assimilated. Consider this

poem by Gomringer, the father of concrete poetry, which can be read or

felt along any of its axes.

"Wind" by Eugene Gomringer.

This type of writing highlights the movement of words and the

balance between form and content.

The visual and semantic elements constituting the form as well as the

content of a poem define its structure so that the poem can be a

"reality in itself and not a poem about something or other."

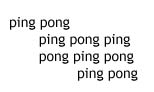

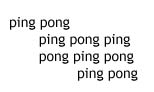

"Ping Pong" by Gomringer shows the tension between similar words that

can create feeling to the reader. There is an acute balance of meaning

possible because of the word arrangements available to the poet.

Their principles are that concrete language structures do not follow

tradional verse forms and are largely visual. As such, the content is

strongly related to the question of attitudes towards life in which

art is effectively incorporated and hence concrete or visual language

is parly reflected and partly unreflected information which often uses

sign schemes.

Importantly, visual language is reduced language;

this is achieved primarily through an acute awareness of graphic space

as a structural agent within the composition of the piece. Finally,

visual poetry aims at the least common multiple of language. It is

simple mind presentation and uses a word arrangement and linguistic

means (such as sounds, syllables, words) which are independent of and

not representative of objects extrinsic to language.

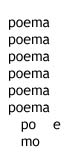

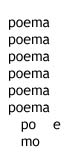

Consider these three famous examples of concrete poetry:

Edgard Braga (1963)

poema = poem

po = dust

e=and

mo = millstone

******************

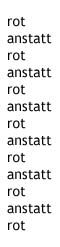

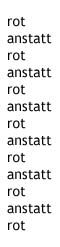

Freidrich Aclleitner (195?)

rot=red

anstatt=instead of

Here the plot thickens when the poem is seen with each "rot" in a

different colour.

****************

Claus Bremer (1966)

The letters of a simple text, "for you and for me", are arranged in

the last five lines to their alphabetical priority.

The concrete poetry movement of the 1950s and 1960s had its roots both

in Surrealism and Dada and prior to that in the writings of the French

symbolists, especially Apollinaire. All these movements are related in

some way to the upheaval of thought and events that characterise the

dramatic differences between the 20th century and the preceding one:

advances in the technology of transportation, communication, and

warfare; new concepts in philosophy and psychology, and the resultant

confusion and change in the behaviour and even the structure of

society.

In a sense, they were artistic movements taking advantage of the

tremendous changes in the nature of everyday life at the beginning of

the twentieth century. While the Impressionists acknowledged the

importance of grasping the fleeting moments of experience, the

tendency in the painting of that movement and of the

Post-Impressionists was to freeze those moments rather than to glorify

the inherent motion. Similarly, the poetry of the Symbolists,

Surrealists and the Cubist movements represented in many cases a

withdrawal from the activities of an industrialised society and the

seeking of a new form of poetry that would communicate emotion in this

"brave new world."

Consider this example of Apollinaire where he has used his own

handwriting to make the letters of his figure.

COMPUTER POETRY (Now)

The publishing industry has remained virtually unchanged since 1455

when Guttenberg first printed the Bible. Not only the publishing

industry, but also the act of reading, unchanged for several

centuries, is now being altered. In the case of computer CD-ROMs,

reading has become an active, participant-directed process rather than

passive, author-directed: turning pages in a book has been transformed

into hypertext links. The rational-visual act of reading has become an

experience of sight, sounds, and colours. As would seem obvious,

writing techniques are also being profoundly altered. The poet of the

future will have to be a more complete and unspecialized artist who

will need to blend his writing skills with oral and artistic abilities

and even more so with technological-computer knowledge. This, together

with computer software that allows active participatory reading and

even the introduction of modifications made by the reader in the work

of art, will perhaps help to rehumanize literature and achieve the

Surrealist, Cubists and Dada poets and writers's unfulfilled dream of

merging art and life.

Consider these examples of animation through the use of Java software

where the words employed in the poem are set in motion.

Or, a poem written with binocular reading in mind where the poem

presents different letters and words to each eye simultaneously.

Binocular reading takes place when we read one word or letter with the

left eye and at the same time a completely different word or letter

with the right eye.

Colour is important in computer poetry. Have a look.

Here colour is not fixed. The poem changes colour and shading.

Discontinuous space computer poetry is where the static presentation

of the three-dimensional space of a poem is broken down into different

spaces that may or may not overlap in space or time. i.e a poem can be

3 dimensional.

Another trend of computer poetry is discontinuous syntax where the

words/syntax alter throughout the reading.

Other future directions are the Hyperpoem which is a digital

interactive poem based on hypertext that branches out as the reader

makes choices along the way. Hyperpoems promote a disengagement of the

textual distribution characteristic of print.

In common with the great concrete poets of the 1950s and 1960s,

computer poetry is composed more for the eye than the ear. The form

of the poem on the page or compuer screen affects how we read it and

so affects our experience of its meaning. In computer poetry,

however, the image or text becomes an object of comprehension "within

itself". In common with the past this is achieved by syntactic

techniques within the text and the use of white space;

juxtapositioning of images and ideas as well as the use of other

printed mediums within the visual poem.

Computer poetry will and does employ these techniques. Moreover the

Internet and associated software has opened poetry, and in particular,

visual poetry, to a feast of new possibilities including animation,

clip-art, hypertext links, rhythms of perception and new

possibilities of spatial form.

A final question: Will the future poet need to be as much of a

computer software expert as they are artist or craftsman? The future

will tell us.

FURTHER READING:

Richard Kostelanetz, Wordworks, N.Y. BOA, 1993.

Seaman, David, Concrete poetry in France, Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1981.

Sharkey, John (Ed), Mindplay: An anthology of British Concrete Poetry,

London, Lorimer, 1971.

Williams, Emmett(Ed), An Anthology of Concrete Poetry, N.Y., Something

Else, 1967.

Solt, Mary Ellen (Ed), Concrete Poetry: A World View, London, Indiana,

1971.

Levenston, E.A. The stuff of literature: physical apects of texts and

their relation to literary meaning. New York, N.Y. U. Press, 1992.

Gumpel, Liselotte, Concrete poetry from East and West Germany; Yale,

New Haven, 1976.

Jackson, K.D (Ed)., Experimental-Visual-Concrete:

Avante-Garde poetry since the 1960s, Atlanta, GA, 1996.

__________

Paul Kloppenborg is married to Deb and has 2 children,

"and it's this family who has to put up with my passion for writing and

critting."

Paul wasn't always as passionate about poetry. When he left University

in the early 1980s, he wanted to establish a career. So with his History degree under one arm and a Diploma in Librarianship under the other, he started work in a variety of

libraries, both public and technical, helping people find and use

information. It was this constant drenching in

words, paper, books and information that kick started him

along the road to writing.

Paul is involved in a number of writing/poetry workshops and has seen his work published in

numerous paper and electronic publications, including "A Year on the Avenue", a joint poetry book published last autumn by Two Dog Press. He is the Fiction Editor at "Recursive Angel."

|