| Chimes

At Midnight Revisiting the Shakespearian Welles by Mike Shen |

|

INTERVIEWER: What is your major vice? ORSON WELLES: Accidia -- the medieval Latin word for melancholy, and sloth… I have most of the accepted sins -- envy, perhaps, the least of all. And pride… INTERVIEWER: Do you consider gluttony a bad vice? There must have been good feelings, and good wine, flowing in the hotel room where that interview took place, for Welles took no offense at the question. "It certainly shows on me," he admitted. "But I feel that gluttony must be a good deal less deadly than some of the other sins. Because it's affirmative, isn't it? At least it celebrates some of the good things of life."

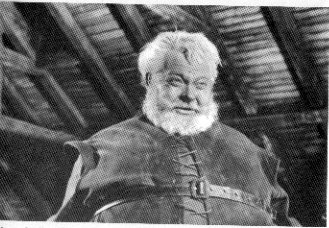

CHIEF JUSTICE: Your means are very slender, and your waste is great. FALSTAFF: I would it were otherwise; I would my means were greater, and my waist slenderer. Boasting an excellent cast, including John Gielgud as Henry IV and Margaret Rutherford as the addled Mistress Quickly, Chimes at Midnight nonetheless belongs to Welles; here, as in Touch of Evil, the director makes inspired fun of his own face, exaggerating, with wide-angle lens, the Santa Claus jowls, the inflamed, merry bulb of a nose. He carries his bulk with wonderful grace, sprinkling the performance with minute, almost imperceptible bits of physical comedy -- a hand on the gut, a wobbling of the knees, a quick ballooning of the cheeks. But the accidia comes in handy too, as Welles explores the tragic side of Falstaff, the impoverished, disease-ridden loser who, in Shakespeare, doesn't even get to die on the stage. In creating Chimes at Midnight, Welles stitched together pieces of five plays -- Richard II, Henry IV 1 and 2, Henry V, and The Merry Wives of Windsor -- to tell the story of Falstaff's friendship with Prince Hal, and of the prince's eventual rejection of his companion. The film shakes up the chronology of the plays; conversations that begin in The Merry Wives of Windsor finish up in 2 Henry IV, characters pop up in the wrong places, and two battle scenes merge into one. "Naturally, I'm going to offend the kind of Shakespeare lover whose main concern is the sacredness of the text," Welles told an interviewer. "But with people who are willing to concede that movies are a separate art form, I have some hopes of success." In the plays, Hal's morality is ambiguous; his betrayal of Falstaff is a necessary means to restore honor to the crown and stability to the realm. But Welles glosses over the political dimensions of the plays, preferring to emphasize the human story of Falstaff's betrayal. Practically all of Henry V, in which Hal conquers France in five acts, is squeezed into a single, ironic line of voiceover: as the narrator extols the greatness of the new king, we cut to Falstaff's rowdy tavern crew, rolling away an enormous casket. Falstaff, of course, has died, for "the king has killed his heart." The words may be Shakespeare, but the aesthetic -- fast-moving, oblique, deliriously off-balance -- is unmistakably Welles, and the eight-minute battle sequence, a whirl of galloping hooves, whizzing arrows, and broken heads, is among the greatest in film history. The blocking is deft, the camera placements unexpected and precise; yet at the same time, there is something profoundly unfussy about Welles's style. There's plenty of room left, in those famous deep spaces, for the best dialogue ever written. "You always overstress the value of images," Welles once told a critic. "Only the literary mind can help the movies out of that cul-de-sac into which they have been driven…" Only a formalist of Welles's standing could get away with such heresy. For movie buffs, literary adaptation is a red flag. (Think of Joel McCrea in Sullivan's Travels, as the misguided Hollywood director who wants to make a pretentious lit-film called O Brother, Where Art Thou?). It touches on our deepest fear, that cinema is still poor cousin among the arts. Remembering Orson Welles -- the man behind Chimes at Midnight, Othello, The Magnificent Ambersons -- should help us to rest a little easier at night. --Mike Shen Discuss this article on the nextPix FORUM by going to its discussion thread: [click here] The interviews quoted in this article are reprinted in Orson Welles: Interviews; ed. Mark W. Estrin, University Press of Mississippi, 2002.

|

| |

|

Euro Screen Writers Articles on Euro film, research, plus a great cache of interviews with such directors as Godard, Besson, Agnieszka Holland, Peter Greenway, and Fritz Lang. |

|

Done Deal: A current list of the latest industry script sales. |

|

UK's Film Unlimited Truly unlimited, one of the best film sites going. Plenty of news, reviews, special reports, features, and PREVIEWS. |

|

Screen Writer's Utopia! What are they, who wrote them, who's doing them, and what you can expect. |

Welles

was in London; it was 1966, and he was acting in the James Bond

film Casino Royale. He was about to unveil Chimes at Midnight,

his film adaptation of Shakespeare's Falstaff plays, at Cannes.

A quarter-century had passed since Welles, as a limber twenty-six

year old, had made Citizen Kane; he had put on the fat that he would

wear for the rest of his life, and, purely on physique, made a magnificent

Falstaff. Life, too, had given him insight into Shakespeare's most

popular rogue. "The truth of Falstaff," he would later observe,

"is that Shakespeare understood him better than the other great

characters he created, because Falstaff was obliged to sing for

his supper." Falstaff was cherished for his wit but scorned for

his decadence; Welles was celebrated as a genius even as he struggled

to finance his films, accused of frittering his talent, and, more

deadly to his career, of squandering studio money. As Falstaff,

Welles offered his rebuttal on-screen:

Welles

was in London; it was 1966, and he was acting in the James Bond

film Casino Royale. He was about to unveil Chimes at Midnight,

his film adaptation of Shakespeare's Falstaff plays, at Cannes.

A quarter-century had passed since Welles, as a limber twenty-six

year old, had made Citizen Kane; he had put on the fat that he would

wear for the rest of his life, and, purely on physique, made a magnificent

Falstaff. Life, too, had given him insight into Shakespeare's most

popular rogue. "The truth of Falstaff," he would later observe,

"is that Shakespeare understood him better than the other great

characters he created, because Falstaff was obliged to sing for

his supper." Falstaff was cherished for his wit but scorned for

his decadence; Welles was celebrated as a genius even as he struggled

to finance his films, accused of frittering his talent, and, more

deadly to his career, of squandering studio money. As Falstaff,

Welles offered his rebuttal on-screen: