| Faulkner

on Film Obliquely Translating a Master by Mike Shen |

|

It's said that once, during his unhappy years as a screenwriter in Hollywood, William Faulkner accompanied Howard Hawks and Clark Gable on a hunting trip. After a few hours of characteristic silence, Faulkner was heard to mumble something about literature, and Gable asked him who he thought were the best living writers. "Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Willa Cather, Thomas Mann, and me," said Faulkner. "Oh," said Gable, "do you write books?" "Yes," said Faulkner. "What do you do?" I

first heard this yarn after a screening of what has since become

one of my favorite films: 1957's The Tarnished Angels, adapted

from Faulkner's novel Pylon. In a way, I'm surprised that

I can remember anything that was said to me in the first six hours

after I'd first seen this small Faulkner

didn't write the screenplay, though he considered it the best of

the movies made from his books. "Thought it was pretty good, quite

honest," he said. "But I'll have to admit I didn't recognize anything

I put into it." Faulkner had no illusions Pylon is not Faulkner's best novel; he turned it out quickly, while taking a break from writing Absalom, Absalom! But the prose is keenly affecting nonetheless, and well-matched to its subject; the sentences rush (and run) on, finding their ends in a kind of terminal exhaustion, like the pilots who circle the pylons again and again to their deaths. A young German film director named Hans Detlef Sierck read the book in 1936, approached his studio for a commission, and was turned down flat. A year later, he left Nazi Germany for Hollywood. It would be two decades before Sierck, now Douglas Sirk, a highly successful director of domestic melodramas, would have his chance to bring Faulkner's novel to the screen. As scholar Michael Stern has written, Sirk's and screenwriter George Zuckerman's strategy was "to extract from the novel's ghostly and intangible prose a concrete sense of the logic behind it." The narrative circles of Faulkner's novel -- the endless trips between the town and the airport, the purchase and pawning of a pair of boots, the fluctuating employment status of the drunken reporter -- find their onscreen counterparts in visual background motifs: the imprisoning shadow of a spiral banister, the glare of a revolving airfield light, the ferris wheel, the revolving airplane ride on which the young boy emulates the pilots. In the film, Hudson's editor refers to the airshow as a "cheap crummy carnival of death"; this notion is externalized through an elaborate pageant of Mardi Gras imagery. Sirk's New Orleans is a world of grotesque masks, of funhouse mirrors, and of furious bacchanalia -- the civilian's equivalent to what goes on in the air, around the pylons.† The reporter is hopelessly smashed for most of the novel, which lurches around behind him; Hudson, in contrast, comes off as a purposeful drunk, a well-meaning meddler who advances the plot. The cinematic Shumanns, too, differ from their novelistic namesakes, who are uniformly venal and, in this sense, hard to tell apart. The film assigns them personalities, further etched into generic types. Hence Laverne, instead of responding to Roger's death with a string of curses, now weeps sweetly; Jiggs, in the book an ornery alcoholic, becomes a big-hearted galoot. Most notably, the character of the parachute jumper, who in the book alternates with Roger as Laverne's lover, is excised entirely, leaving a neat love triangle instead of a clunky quadrilateral. It may sound like bowdlerizing, but it works: as Faulkner put it, screenwriting is a very different racket. There are, admittedly, some hamfisted moments: Stack, for example, declaring with the twitching intensity that would later be parodied in Airplane, "I need this ship… like an alcoholic needs his drink!" Later, he tells Malone that he'll quit racing, so they can make a new start together. Just one last turn around the pylons -- against a guy named Crash Wilson. But the laughs are there mostly for those who came in to laugh, and the irony is evident for anyone who cares to look, as when Hudson delivers his drunken monologue about love, death, and the flying machine to a bunch of colleagues in the newsroom. "IS IT INTERESTING" asks a printed sign hung in the background: whether you are caught up in Hudson's excitement or warned against it depends on the kind of moviegoer you are (neither kind being better than the other). At the end of the film, Malone boards an Iowa-bound plane, clutching a copy of My Antonia. It's easy to forget, as Hudson smiles and the naïve, gorgeous score sweeps over us, that in the world of this film, airplanes do not bring happiness. "I told Rock… [that] Malone at the end there was going back to the cornfields, to the earth, to her youth," said Sirk, in a later interview. "Of course, I didn't tell him she was only trying to go back." --Mike Shen Discuss this article on the nextPix FORUM by going to its discussion thread: [click here] †For a definitive formal analysis of The Tarnished Angels and other Sirk films, see Stern's book Douglas Sirk (Twayne Publishers, 1979). |

| |

|

Euro Screen Writers Articles on Euro film, research, plus a great cache of interviews with such directors as Godard, Besson, Agnieszka Holland, Peter Greenway, and Fritz Lang. |

|

Done Deal: A current list of the latest industry script sales. |

|

UK's Film Unlimited Truly unlimited, one of the best film sites going. Plenty of news, reviews, special reports, features, and PREVIEWS. |

|

Screen Writer's Utopia! What are they, who wrote them, who's doing them, and what you can expect. |

masterpiece,

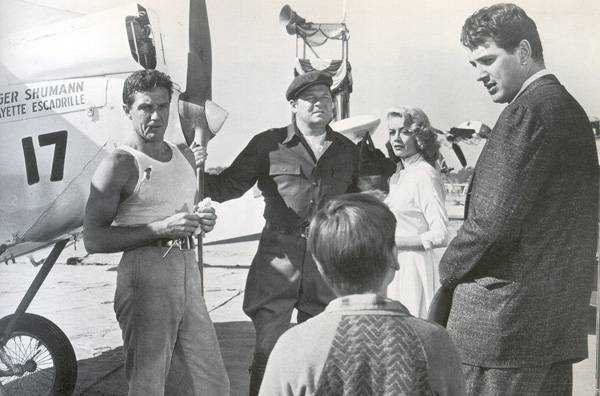

which tells the story of a Depression-era New Orleans reporter (Rock

Hudson) assigned to cover an aviation show. Fascinated by the death-defying

pilots who race their planes in circles around the pylons, Hudson

falls in with an unorthodox family: a grim pilot named Roger Shumann

(Robert Stack), his beautiful wife Laverne (Dorothy Malone), their

steady mechanic Jiggs (Jack Carson), and Laverne's young son Jack

(Chris Olsen), whose paternity is unclear.

masterpiece,

which tells the story of a Depression-era New Orleans reporter (Rock

Hudson) assigned to cover an aviation show. Fascinated by the death-defying

pilots who race their planes in circles around the pylons, Hudson

falls in with an unorthodox family: a grim pilot named Roger Shumann

(Robert Stack), his beautiful wife Laverne (Dorothy Malone), their

steady mechanic Jiggs (Jack Carson), and Laverne's young son Jack

(Chris Olsen), whose paternity is unclear.

about

his cinematic intuition ("It ain't my racket"), and it's to his

credit that he could find honesty in an overtly commercial film

that diverges seriously from his book. That honesty gripped me,

as much as the tawdry excitement of the race sequences, or the hardbitten

desperation of the film's characters. I sat in my dark room, watching

Hudson and Malone in theirs; I had the sense, as when I first saw

Rebel Without a Cause, that I could, if I chose, simply laugh

the whole thing off and destroy it. But I didn't laugh. Instead

I spent one of the most deeply satisfying afternoons I have ever

known in a movie theater. (This is definitely not one to rent on

videotape; like Rebel, it only flies in widescreen.)

about

his cinematic intuition ("It ain't my racket"), and it's to his

credit that he could find honesty in an overtly commercial film

that diverges seriously from his book. That honesty gripped me,

as much as the tawdry excitement of the race sequences, or the hardbitten

desperation of the film's characters. I sat in my dark room, watching

Hudson and Malone in theirs; I had the sense, as when I first saw

Rebel Without a Cause, that I could, if I chose, simply laugh

the whole thing off and destroy it. But I didn't laugh. Instead

I spent one of the most deeply satisfying afternoons I have ever

known in a movie theater. (This is definitely not one to rent on

videotape; like Rebel, it only flies in widescreen.)