| This

Machine Kills Fascists Why sub-culture no longer exists by Nicholas Rombes |

|

"Real life is becoming indistinguishable from the movies." -- Horkheimer and Adorno, "The Culture Industry" (1944) "Where are our real bodies?" -- eXistenZ (1999) THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS. So said the lettering on Woodie Guthrie's guitar. What links that statement with Herman Goerring's that "every time I hear the word culture I reach for my pistol" is their shared recognition of the raw power of culture: it can kill, and it can make you want to kill. I lost a Canadian friend last week over an argument about Vanilla Sky. "It may not be a good film, but it helps me generate a theory," he said. I called it rotten nonetheless, and he thought I was calling him rotten by implication, and that was that. I don't think he wanted to kill me exactly, but there was one moment there. Critic Greil Marcus once wrote of the avant-garde that "nothing is easier than the provocation of a riot by a putative art statement. . . . All you have to do is lead an audience to expect one thing and give it something else." Which is exactly the reason a film like Vanilla Sky crashes and burns so beautifully: it tells you what to expect, then gives it to you in large, unambiguous doses, a kind of roving, rubber-lipped pedagogue that can't wait to tell you what you already know, what you have known all your life. The frantic replication of reality on TV shows and in movies desperately and unsuccessfully masks the truth that the real is running out -- it's practically all used up. We recoil at movies like Vanilla Sky because they take this central Horror and transform it into beautiful math: Tom Cruise's deformed face or Penelope Cruz's collagen lips -- the film equates them both in order to ensure the same administered experience for the ugly and beautiful alike. There is no moment of doubt, no sideways look, no hesitation in the dirge-like progression of the film that might give audiences a chance to enter into it in a way of their own choosing. "Here is how you are supposed to feel," the film says, and then tries very, very hard to make you feel that way. Cameron Crowe has said that Vanilla Sky is "a movie to think about and talk about later -- that idea was built into it." Does this sort of self-consciousness and manipulation signal the end to the kind of vulnerability that marked the best films of the post-punk film movement, films like Donnie Darko, Ghost World, eXistenZ, Memento, Mulholland Drive, Tape, Gummo, Fight Club, Requiem for a Dream, Time Code, and Being John Malkovich? While these films operated at the forefront of change, anticipating and giving visual and narrative shape to thornier cultural undercurrents, films like Vanilla Sky make orthodoxy out of every radical idea, draining them of danger and fitting them into patterns that are safe and familiar. A movie like Vanilla Sky offers a reproduction not of the illusion of reality, but of the very mechanisms of that illusion -- it's a crummy movie because it tells us what we already know, and then proceeds to show it to us again. While history has shown us that film movements burn out and give way to more sober, official versions of a culture's irrational fantasies, there is a difference today, and that difference has to do with how films live on archived on DVD. Which is to say: DVDs are much more than simple information storage and retrieval devices -- they represent a whole new shift in the relationship between films and viewers. Take the new Special Edition DVD of Christopher Nolan's film Memento. Judging from some of the reaction you'd think everyone who'd seen it was reaching for their pistols. Sure, the DVD has its defenders (there's always somebody who will defend anything) but overall the reaction has been closer to outright hostility. "It's infuriating, it's monotonous, and it's not worth [the money] for the aggravation," is one of the typical hostile user comments on amazon.com.

In this sense, the chapter structure of DVDs is simply an extension of an old movie trick -- the flashback and flash forward, those rare moments in classical Hollywood films where the invisible style of editing (which beautifully disguised the wild temporal and spatial jumps of any film) lost its transparency and became apparent to the audience. The chapter structure of DVDs are extended versions of the flashbacks and forwards, except that today the viewer has a tremendous degree of control over when and where to insert these temporal dislocations. Playing off the idea of an incomplete archive, the packaging on the Memento Special Edition is suitable for a medium that is itself archival (the DVD with its multitude of supplementary features), and especially for a movie whose subject is the unstable archive of memory. If the postmodernists delighted in the demolition of the bogus boundary between reality and illusion, then this DVD never assumed there was one: there is no "real" menu to fall back on, no safe reminder that it's just a hoax. It reveals a movie for what it always is at its best: an elaborate, intimate game between the audience and the film itself. Rather than lessening the power of illusion, it stages it on a whole other level. A good, risky DVD experience reminds you of all the choices available to you in the best films, such as: which characters will you identify with in the film and are these the same characters the film wants you to identify with? Memento withholds the answer to this question as its central thesis and then goes from there. It is the condition of our time the speed at which the notorious, the shocking, the surprising become routine and commonplace and we become bored. Blair Witch. The Osbourne Show. Cloning. Donnie Darko. We barely had time to appreciate their strangeness before they were replicated and we became cynics, the first to say, "that was no big deal after all." This pretty much eliminates the possibility of a subculture: there is simply no time for an underground identity to develop before it finds its way into the mainstream. Speed itself becomes the new value: content is merely the parasite that rides the speed beast. The very rapid-fire process of incorporation of the radical into the norm all but obliterates differences between marginal and mainstream; after all, what is the mainstream today other than an amalgamation of modified subcultures? The DVD format is ideally suited to this fact, as its very technology gives us the possibility of choice (options, bonus materials, menus), so that in addition to the selection among films, we also have available selection within a film-the power to rearrange the story in a sequence of our choice. Soon we will also be able to re-edit movies, as well as add or subtract content, delete lines, modify transitions between scenes, even cut in scenes from other movies (this is already happening on the internet). The new art will be one of pastiche, where the notion of dominant authorship-the auteur theory-is truly dead. This was predicted back in 1968 by Roland Barthes, who wrote that "the removal of the Author . . . is not merely an historical fact or an act of writing; it utterly transforms the modern text," and that "the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author." Which is why Memento -- even in its crazy Special Edition DVD format -- makes so much sense, and why Vanilla Sky is an anachronism. Audiences already know that the real was used up a long time ago, that the Author is dead, and that what we're left with is inventive rearranging, a game that Memento knows how to play with savage humor, both in the film itself and in its exploitation of the DVD apparatus. On the Memento DVD -- and on others like Donnie Darko -- the film itself is lost, an afterthought. And isn't that the savage attraction of movies like Memento in the first place, the secret knowledge that we are aliens, most of all to ourselves? Who is this man? Who is this nation? What war is this? So what if I can't find my way around the DVD --even if I could navigate it, I couldn't remember how I did it. What was it I was searching for? Okay, there is Leonard, doing it again, forever. The post-punk film spirit lives on, even after the movement has ended, embodied in DVD archives that remind us that even though the real was shattered long ago, there is still much fun to be had in fucking with the pieces. Like Leonard, I'm an imposter. I'm free of history, roaming a fragmented world. I have been liberated. So have you. -- Nicholas Rombes

Discuss

this article on the nextPix FORUM by going to its Nicholas Rombes is a professor of English at the University of Detroit Mercy, where he teaches courses in film, creative writing, and postmodern literature, and where he co-edits the journal Post Identity. His essays on David Lynch, Fight Club, and serial killer cinema have appeared in CTHEORY, Post Script, and numerous other journals. He writes regularly on new music for Exquisite Corpse, where his fiction has also appeared. |

| |

|

Euro Screen Writers Articles on Euro film, research, plus a great cache of interviews with such directors as Godard, Besson, Agnieszka Holland, Peter Greenway, and Fritz Lang. |

|

Done Deal: A current list of the latest industry script sales. |

|

UK's Film Unlimited Truly unlimited, one of the best film sites going. Plenty of news, reviews, special reports, features, and PREVIEWS. |

|

Screen Writer's Utopia! What are they, who wrote them, who's doing them, and what you can expect. |

In

case you haven't seen it, the DVD comes packaged as a psychiatric

report "in the matter of an application for the admission of Leonard

Shelby an allegedly sick person," complete with a plastic paperclip

holding together a sheaf of papers, including a medical history

and a portion of a police department report which is actually a

brief set of directions for how to play the movie (there are no

directions, or menu for that matter, for how to access the supplementary

features). It emerges from the same ethos that sprung Mark Danielewski's

novel House of Leaves or Ben Marcus's book Notable American

Women or music by the Yeah Yeah Yeah's, where you never

know if it's serious or even if it's real. To get the movie to play

in a rearranged chronological order, you need to find a panel of

illustrations showing a woman with a flat tire and arrange the actions

in reverse sequence.

In

case you haven't seen it, the DVD comes packaged as a psychiatric

report "in the matter of an application for the admission of Leonard

Shelby an allegedly sick person," complete with a plastic paperclip

holding together a sheaf of papers, including a medical history

and a portion of a police department report which is actually a

brief set of directions for how to play the movie (there are no

directions, or menu for that matter, for how to access the supplementary

features). It emerges from the same ethos that sprung Mark Danielewski's

novel House of Leaves or Ben Marcus's book Notable American

Women or music by the Yeah Yeah Yeah's, where you never

know if it's serious or even if it's real. To get the movie to play

in a rearranged chronological order, you need to find a panel of

illustrations showing a woman with a flat tire and arrange the actions

in reverse sequence.

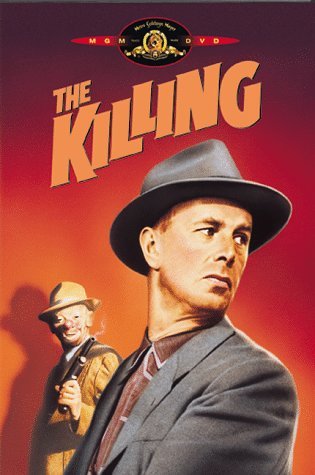

This

requires some time, to be sure, but its subversive gesture is in

acknowledging that the arrangement of information in any narrative

is matter of strategy and choice, a process normally denied the

viewer when watching a film. What began as experiments in Stanley

Kubrick's 1956 film The Killing or in the cut-up method as

practiced by William S. Burroughs in his writing are now part of

the logic of almost every new DVD, which allows viewers to reconstruct

a movie in blocks, or chapters. This puts the responsibility for

the creation of meaning more squarely on the shoulders of the viewer:

depending on which of the many deleted scenes I choose to watch

on, say, the Donnie Darko DVD, and in what order I choose

to watch them, my experience and understanding of the film is likely

to be much different than yours. In fact, it's not only possible

but likely that you and I won't even ever watch the same "version"

of the film; it's democracy verging on anarchy.

This

requires some time, to be sure, but its subversive gesture is in

acknowledging that the arrangement of information in any narrative

is matter of strategy and choice, a process normally denied the

viewer when watching a film. What began as experiments in Stanley

Kubrick's 1956 film The Killing or in the cut-up method as

practiced by William S. Burroughs in his writing are now part of

the logic of almost every new DVD, which allows viewers to reconstruct

a movie in blocks, or chapters. This puts the responsibility for

the creation of meaning more squarely on the shoulders of the viewer:

depending on which of the many deleted scenes I choose to watch

on, say, the Donnie Darko DVD, and in what order I choose

to watch them, my experience and understanding of the film is likely

to be much different than yours. In fact, it's not only possible

but likely that you and I won't even ever watch the same "version"

of the film; it's democracy verging on anarchy.