|

an ongoing series by Thomas E. Kennedy and Walter Cummins

photo by Alice M. Guldbrandsen |

"The Best Bookshop in England

Since 1879": Blackwell's of Oxford

Essay and Photos by Walter Cummins

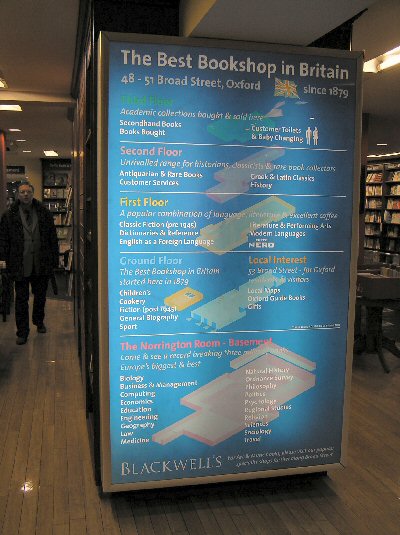

The Norrington basement offers a bibliophile's paradise, home of books on biology, business and management, computing, economics, education, engineering, geography, law, medicine, natural science, ordinance survey, philosophy, politics, psychology, regional studies, religion, sciences, sociology and travel. The largest room devoted to book selling in Europe, its ten thousand square feet extend into excavated space beneath the Trinity College Gardens, thousands of books layered on several acres of shelving. The staff was even thoughtful enough to post a sign noting “Photo Spot” on one ramped tier. Sure enough, standing there opens an imposing vista, and it's where I snapped the digital shot that follows.

In addition to selling books, Blackwell's began publishing them immediately in 1879 and then, in 1922, founded a separate publishing arm, Basil Blackwell & Mott. Before World War Two, that house put out books by emerging writers such as WH Auden, Graham Greene, and JRR Tolkien. The output ranged from inexpensive versions of classic works to fine printed belles-lettres editions. After the war, it became a major academic publisher, including all the papers of Ludwig Wittgenstein in 1973. Now the press is responsible for 750 journals, close to 5,000 books in print, and an annual output of more than 600 new works. The 2001 merger of Blackwell Publishers and Blackwell Science created Blackwell Publishing, the world's largest independent society publisher.

Near the east end of Broad Street, just past the buildings of Balliol College, in another world from the pedestrian mall of Cornmarket Street, where neon blazons the latest 21st-century goods, Blackwell's bookstore occupies numbers 48-51, a row of antique structures several stories high, tall multi-paned windows on the ground level revealing a universe of books within. The fact that two of the buildings are interrupted by a smoky basement pub with the ubiquitous name of The White Horse suggests a Dickensian aura. But Blackwell's is post-Dickens, founded for rare and secondhand books by Benjamin Henry Blackwell in 1879, which makes it a recent addition in the context of Oxford history, where New College dates from 1379, six hundred years earlier. Yet in that relatively short time the bookstore has become a fixture, known throughout the world. That original store at number 50 occupied just twelve square feet, into which were crammed 700 volumes. The present store contains 250,000.

Blackwell's on a late winter afternoon

I first learned of Blackwell's in the 1950s through its airmailed pamphlets listing books on sale, just black ink on white paper. In that post-war time, when European economies functioned at a very different scale from America's, book prices in England were much lower, a package from Blackwell's a bargain even with shipping fees. Eventually, that advantage disappeared and American books became substantially cheaper, European visitors to the States now stuffing books into their luggage along with inexpensive linens and clothing. Still, Blackwell's thrives.

about the city, with 26 additional branches throughout the UK, especially in university towns, and seven shops each in London and Edinburgh.

I don't recall if I ever mail-ordered books from Blackwell's, though I'm sure friends did. When I lived in a village near Oxford in the 1970s and drove to the city several times a week, I made my first visits to the bookstore and its appendages, including a small children's shop, where I collected a series of educational Ladybug books for my young daughters. Blackwell's has a number of other adjuncts, two of them across Broad Street, featuring music and art. Others, including the university bookstore, are scattered

It's the main store that amazed me the first time I entered and found myself inundated by choices. Those narrow storefronts are deceptive, like passing through a small doorway and finding yourself in a great cathedral. But, in contrast to a cathedral, the store does not overwhelm the senses with soaring naves and vast open spaces. Here it's books by the thousands, lined on shelves, stacked on tables, five levels of them on floors that reach far back into the city. The original back walls of the buildings are long gone, replaced by deep extensions.

Directly inside the main door, one is greeted by a floor plan directory indicating where to find what: recent fiction, cookery, children's books, biography, and sport on the ground level; literature and languages, classic fiction, and dictionaries and references on the first; classics, history, and antiquarian and rare books on the second; and secondhand books, book buying, and customer toilets and baby changing on the third.

But the numbers – books issued, books stocked, miles of shelving, square footage – don't really capture the experience of a visit to Blackwell's, the sense of being enveloped in a world of books, the mindboggling choices, the rich scent of ink on paper, the aura of all the young Oxfordians who traversed the same floors before they wrote works that took their places on the shelves. So different from clicking “Add to Shopping Cart” and imagining people in running shoes – or perhaps automatons – scurrying about a huge warehouse. But Blackwell's – inevitably – has gone that route too, becoming the first UK bookseller with an online site in 1995.

It doesn't substitute for a real visit. Unable to resist, my American colleagues buy more than they can pack, straining the seams of their checked luggage and straining their arms to carry them home. And you never can tell who else will be lured by Blackwell's. Just this past January, 2006, Martin and I came back to the first-level café, where Renée and Paula were seated at a table with a pile of books, Louise, Liz, and Lisa on padded chairs across from us, and a woman engrossed in reading at the next table.

We noticed that among Renée's books was one by Alice Oswald, but Renée told us she was disappointed because it was an edited anthology, not a new collection of Oswald poems. I should explain that we had first learned of that poet from Jeanette Wintersen several years ago when she appeared at our MFA residency in Wroxton. Asked who she was reading at the time, Wintersen told us she preferred poets to fiction writers and especially liked Alice's Oswald's Dart, a long poem about a river of that name in her home shire of Devon and winner of the 2002 T.S. Eliot Prize. Immediately, several of us found a bookstore copy and were equally impressed. Martin started an inquiry to see if we could get the poet to come to a future residency, with no success.

We were explaining all that to Paula, with Renée emphasizing how much she liked Dart and noting that Oswald's first book, The Thing in the Gap-Stone Stile, was out of print, the only copy she could find on the Internet costing $300. I asked to look at the new anthology, checking the dust jacket for biographical information on Oswald and seeing her photo. When he got a glimpse of the photo, Martin reacted quickly, asking me for the book and studying the photo, looking from it to the woman reading at the next table and back again. When their eyes met, the woman swept up her coat and disappeared down the stairway. It was Alice Oswald.

After a few moments of stunned silence, our collective reaction was, “Well, we'll never get her to come now.” She didn't want to be discovered. That was verified when I found an online piece on Oswald from The Observer, in which Kate Kellaway writes, “Intellectually robust, she also has something of the deer about her - she startles easily, finds exposure difficult (one of her favourite poets is Sir Thomas Wyatt: 'They flee from me, that sometime did me seek ...'). She is impatient, I suppose, with the idea that personality is of interest.” She certainly didn't want our interest.

By the way, Oswald read classics at St. John's College, Oxford, and probably knows every nook and cranny of Blackwell's. If she had stopped to speak to us, she probably would have said, “It's the books that really matter.” But, of course, that's why Blackwell's exists.

[copyright 2006, Walter Cummins]